ART

Noticing that my art has lately been turning into a documentation of flux, movement, chaos—things that are troubling and uncontrollable (climate change and its transformation of the planet, economies, and government), brings to mind the concept of “hyperobjects,” a concept discussed in depth by philospher/ecologist Timothy Morten. A hyperobject is a vast, nonlocal event (although localities, humans, and animals are affected by them in various ways); for example, a pandemic, light, sonic waves, or climate change.

Musician Claudia Molitor and visual artist Christopher T. Wood are artists who have shifted their perspectives from viewing their creations as discreet objects by single individuals to “objects” that are in response to, and interdependent with, vast ongoing hyperobjects on trajectories that may be beyond the artists’ ability to perceive wholly. Molitor writes:

“One of the questions raised by thinking about hyperobjects in relation to composition is what it might mean for compositional practice to consider itself part of a bigger whole rather than a discrete activity by a singular entity producing seemingly self-contained events. We could consider composition from a collaborative and collective perspective, and as practitioners rethink what the act of composing then comes to mean.”

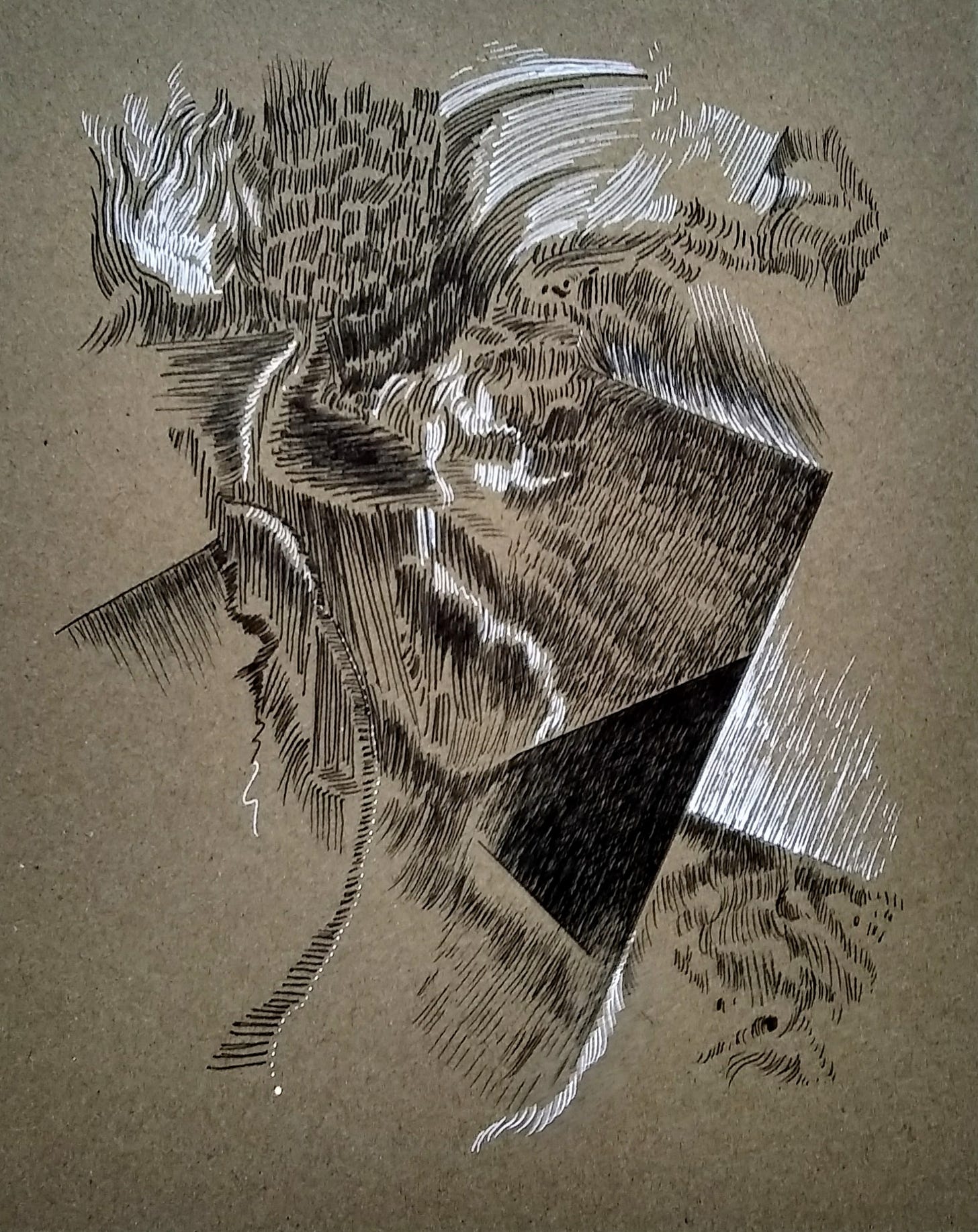

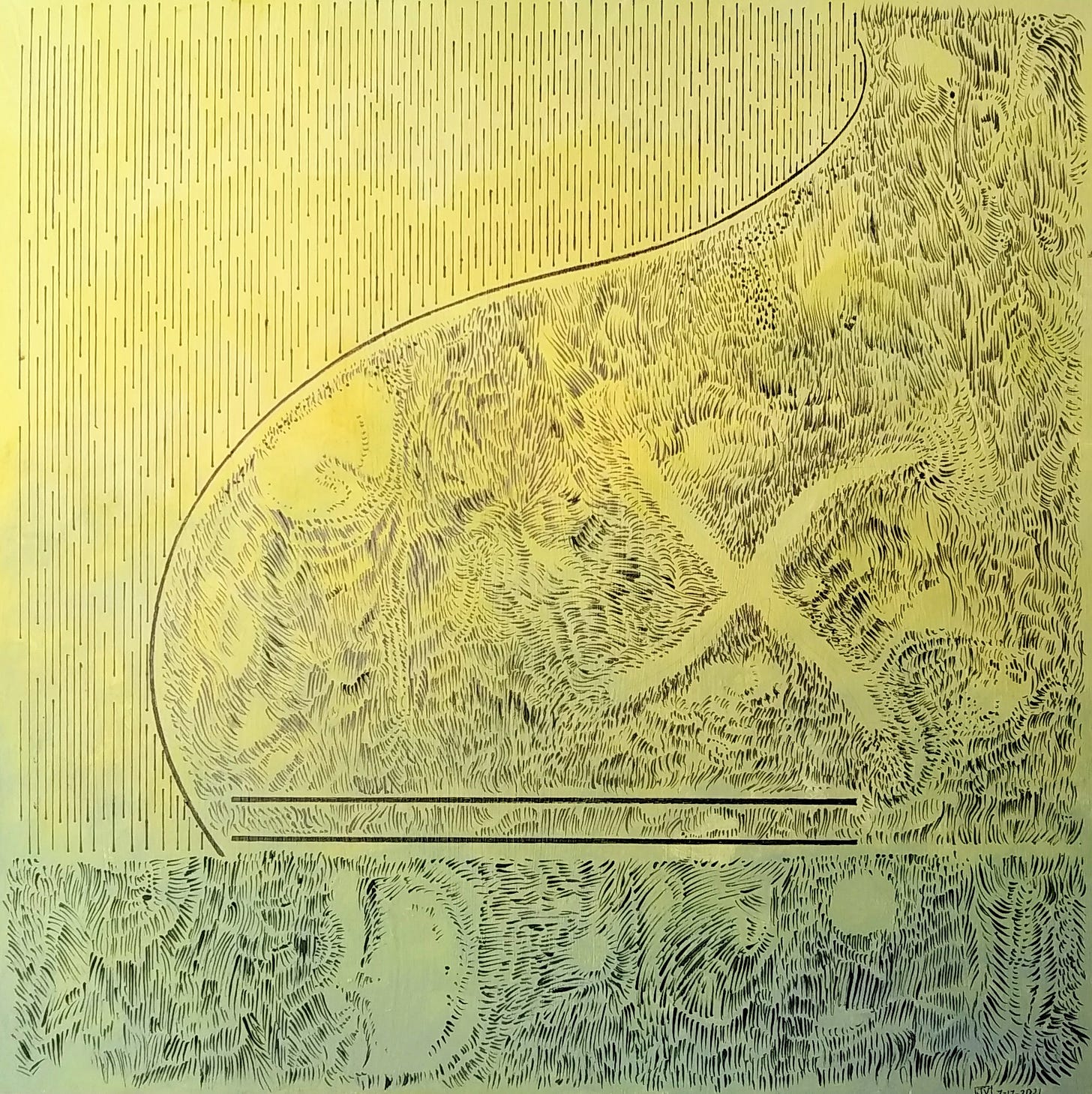

Wood describes what’s behind his “Daydrawing” project:

“I create daily drawings, which accumulate to form an entity we can experience directly but is so distributed in space and time that it does not exist anywhere in particular… It is both local and becoming increasingly dispersed as the fragments drift away from one another through digital publication, collection, and exhibition. It is of critical importance to understand Daydrawing as a single object, continuously in creation and existing in many locations at once.”

While their art is created in relation to the unfathomable, there is also a human and local scale involved. Which leads me to the Filipino concept of kapwa.

In “Roots of Filipino Humanism: (1)"Kapwa," (pressenza.com) Karina Lagdameo Santillan explains, “Researching into the origin of the word “Kapwa,” I came across this. It seems that the word originated from two words: “Ka– a union that refers to any kind of relationship, a union, with everyone and everything. Puwang– space.” So, interestingly, Kapwa seems to define both the local and the vastness of space.

Kapwa refers mainly to individuals and individual identity always in relation to other individuals, and part of something larger, which could be a community, humans globally, or an ecosystem itself related to something larger that we can’t yet understand; it may be called “god(s)” or “universe” or whatever helps one grasp the idea.

The pressure to define an artist’s individual “style” or oeuvre is often simply marketing, a survival tactic in a disintegrating market system. What will replace it? Survival, on an individual human level, is not a small thing—at least for humans and their loved ones. But maybe it’s time for a change in perspective, as the earth and waters shift beneath us and the air becomes smoke.

Santillan goes on to say:

“The list of Filipino or Tagalog words that start with the prefix ka- is long. While I am not a linguist, it signals the sense of sharedness and relatedness we have that underpins Filipino personhood. With the arrival of Western colonizers—first the Spanish, then the Americans, with the passing of time, this sense of shared identity has been suppressed, overlaid with Western individualism and values; and, a world-view that separates oneself from the other.”

Similarly in the “Hyposubjects” project, Dominic Boyer and Timothy Morten ruminate on being “hyposubjects,” i.e., a being that, in its humble smallness (i.e., not a hyperobject, though affected by it) slows down to look around carefully, to listen, and to see:

“We are seduced by despair, and yet despair always twins into hope, even if hope these days is of a curiously objectless and affectless variety; more precisely, hope has itself become a desired object, and yet we are stunted by the unimaginableness of a future that does not repeat the past. The question that motivates me today is, how can we learn to hope for something in this cruel world, the anthropocene? Quoting Roy Scranton: “Can we hope deeply enough that this something will become a method of being?…adapting with mortal humility to our new reality.”

In “Archiving Hope,” Leny Mendoza Strobel reflects on hope, slowness and smallness, and the limits of “literacy” and documentation:

“I hear the script of cultural conditioning around “legacy” and “heritage”—the importance of keeping records of the milestones that crown our lives. After all, don’t we all need and want to be remembered for our achievements and believe that we have done something good in our lifetime to make the world a better place? Ah, but these feelings are fleeting. A part of me doesn’t really care about the tradition of archiving. Confessing this is … unsettling.

In the absence of archives, what we do have in abundance are the imprints in our hearts, psyche, and our soul where our arms have held each other, when we’ve cooked and fed each other, when we’ve sung and prayed together, and cried together. This is Kapwa—the Self-is-in-the-Other—remembered and embodied every day in the ordinariness of our lives. Recorded in the hearts and minds of our shared Self, we turn to each other through the thick and thin of living in the belly of the beast.”

(I read this keeping in mind that my other “job” is in support of a nonprofit that archives the history of a local, AAPI neighborhood).

So what would it look like for me, as an artist and writer? Honestly, I would be happy to let go of the idea of producing some “discreet body of work” that would be “marketable.” What the fuck, I’m old, anyway. Nobody at this point is even expecting that of me; we live in a time when most people are happy to let the old “disappear.”

I like the idea of just creating a continuing stream of small, loosely connected or disconnected works that—if I live long enough—become too tedious to count (apologies to those who have to decide what to do with them after I’m gone! I promise you that eventually they will all rot and seep into the earth to feed uncountable microbes). Before that ending, perhaps the art will occasionally branch off into strange territory that even I can’t fathom or describe in words. Would it then be entering that puwang, “space” indefinable yet affecting? That could be interesting.

Speaking of countless things, I’ve been thinking of writing a paragraph or two on the ubiquitous art tools we use in making art (mostly analog art, but also for other objects that we might find in our phones and computers. As a mostly analog artist I’m doing this out of curiosity, and also out of a masochistic need to learn about where how and why these things were invented, and how they are produced, used, and discarded by artists. No doubt, I will be horrified, as so often happens went I look into such things. Nevertheless:

THE PENCIL

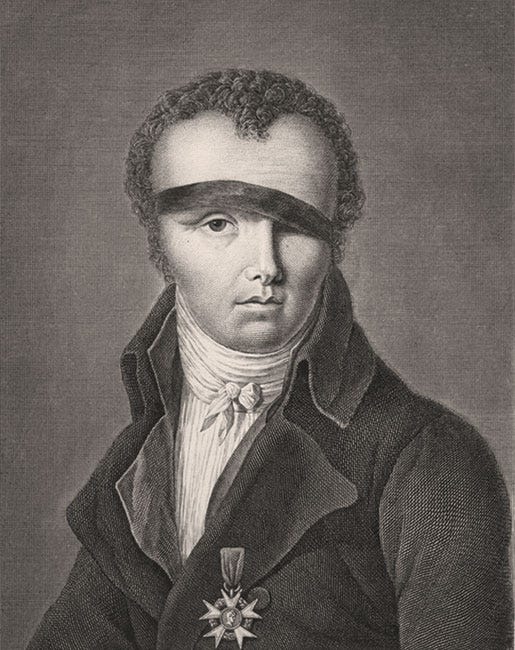

According to most accounts I see online, the pencil as we know it (a piece of “lead” (actually graphite—a crystalline form of carbon) encased in wood) was invented by a French fellow named Nicolas-Jacques Conté, born in 1755, who was an artist, army officer, and balloonist, among other things. Napoleon thought him a genius, and brought him along on his “scientific” expedition to Egypt, where Conté would apply his skills to artistically describe Egyptian life, while embarking on a few experiments that would benefit Napoleon’s project, like, say, studying the physics of mirages. Conté’s first major experiment with flying a balloon over Egypt nearly cost him his life when the balloon caught fire. Suspicious, the Egyptians thought the whole project was to develop a way of burning up enemy camps. Conté continued to document Egyptian life and labors through his drawings and developed a special engraving process to reproduce the detailed artwork.

Since the early 16th century, graphite was being mined and used in England (Cumbria) for marking up things, like sheep. And it was also used to line cannonball molds. But graphite is a messy substance, and back then people who used them for marking wrapped the pieces in leather or rope for easier handling and less mess.

Prodded by the French government and a patron, Conté (also a chemist) successfully mixed the graphite with clay, allowing the French to reduce their dependency on British graphite. He also developed a wooden casing for the graphite that made it much easier to handle. Eventually, Conté and his brother patented the invention and established a pencil-making business in France, where they also produced Conté crayons (another invention by Nicholas). In 1979, the company was purchased by BiC, also based in France. Sound familiar?

Graphite has a LOT of uses beyond pencil “leads.” For example, they are used in lithium-ion batteries in smartphones and laptops. In 2020, China was the largest graphite producing country, with Mozambique and Brazil coming in second and third. Other mining areas include Madagascar, India, Russia, and Ukraine. The pollution issue around graphite mining is serious enough that China has recently begun forcing graphite producers to close. Mining and grinding of graphite creates particulate air pollution, causing bronchial problems, and harsh chemicals are used in processing the graphite, as seen in this video about the effects of graphite mining in Bengaluru:

When I draw with graphite I sometimes (not often enough) wear a mask to avoid breathing the stuff, since I’m sensitive to particle irritation. However, most sources seem to suggest that the stuff is not likely to hurt you unless you it’s in the atmosphere around you on a daily basis. CDC studies show that workers who spend long periods in a graphite-polluted environment could suffer serious health issues.

FIVE THINGS

Bear with me here as I continue with this graphite/carbon thread:

1. Some artists make very literal connections between drawing, line, and bodily movement, such as Tony Orrico’s “endurance” drawings. The performance below was in 2010 :

2. Genevieve Robertson is an artist who works with carbon-based materials. She is very aware of carbon and graphite as both a life producer and a life destroyer, and lives in a mining area in the East and West Kootenays (Canada). In her work she begins with raw material, and breaks it down, physically, with mortar and pestle, and creates her own binders. In this way her art making becomes even more closely involved with the material:

3. General Pencil is a pencil company in New Jersey that’s been around for over 130 years. I have a few of their products in my pencil box; I love the deep blacks that their graphite produces.

4. Deep into the heart of a graphite mine in Sri Lanka:

5. As few years ago, I collected charcoal sticks from oak branches that were burned in the field near where I lived in Elkhorn, but I haven’t used them for much. Recently I stumbled on this video (Rob’s Art Class on Youtube) and learned I can use charcoal to stain paper in interesting ways.

I’m interested in trying that, soon. There’s plenty of burned wood in California right now…

Well, this was an unusually long issue, for Eulipion Outpost. More next week. What art tool should I write about next? I’d love to read your comments. Or visit my website.

Subscriptions are free!