7/30/2022 #74

Here & Now, Boukra Press, Six Questions for Melissa Smedley, Salinas River, Bees, Art Hives, Dept. of Homeland Inspiration, Todd Park Mohr, Natalia La Fourcade.

HERE AND NOW

I haven’t been making much art lately. I’ve got a lot of editing jobs coming up this fall and, although there are gaps between them, they occupy my mind so much that it’s difficult to settle down and make art in any consistent (or even inconsistent) way. All of the contracts support AAPI scholars in one way or another; some of them are in sociology or law, some in museum studies, or in the arts—and I’m glad to contribute my services.

I’m happy to say that Boukra Press (a writers’ collective) will be publishing my poetry/art chapbook, The Epic of Waiting, this year. My poem, “I Would Rather Not,” is featured in their recent blogpost, along with essays and poems by other writers.

When I started the bi-weekly Six Questions and brought other artists into Eulipion Outpost, I hadn’t given much thought to the implications of that project. It just seemed like a cool thing to do. More recently, though, I’ve become curious about the collaborative and collective potential of including other voices, both here in the Outpost and elsewhere. I think of the Outpost as something akin to Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s “duty-free gift” for “the travelers . . . the artists, poets, and . . . Eulipions,” those who, in a sense, are traveling on the same boat to Eulipia.

ART

Today’s Six Questions are answered by multi-talented and generous art alchemist, writer, and podcaster Melissa Smedley. I’ll let her tell the story:

SIX QUESTIONS FOR MELISSA SMEDLEY

1) Where did you grow up and how did that (or any other significant experience) influence your art?

I grew up in Denver, Colorado in a family that settled there in the 1860's when it was still called Queen City of the Plains. Both the location and upbringing did have a profound effect on my formation. We were steeped in family lore descended from a great grandfather from a family of Pennsylvania Quakers, who made his way across the Oregon Trail in 1862. His Victorian era journal describes beautiful vistas as well as a myriad of challenges, like having to stop to build a bridge before being able to cross a creek, troubles with oxen, numerous encounters with “Indians”, then hiking around California for months while awaiting the steamship that would take him back to the East coast. A few years later, he settled in Denver to practice dentistry and start our branch of the Smedley family. (All of this more top of mind as the family is celebrating the 150-year anniversary of this trek and publication of his travel journal.)

Elements of this pioneer spirit and love of mountaineering transferred through my eccentric dad who ate broccoli for breakfast and never doubted that his daughters would be casual endurance athletes. We were brought along on hikes up 15,000-foot peaks where, like he and his brothers, we do a headstand at the summit. We practiced swimming in a lake with carp and geese. We rode our heavy old bikes up mountain passes with no understanding of nutrition or hydration. And we skied down anything. A reverence for creativity and invention also rippled through this family along with details of the Colorado history.

My "renaissance man" dad wrote poems, painted pocket-sized watercolors, and baked rhubarb pies alongside his lawyer-at-the-strip-mall profession. And mom, now still dancing and humming through her 91st year, has anchored herself amazingly around physical fitness, the arts, and friendships, always aiming for her life to resemble being at summer camp. Most definitely growing up in a suburban community with a recreational pond and hand painted street signs that said things like "Ridge Trail" or "Sunset" made me long to experience and wonder over worlds that seemed the opposite of that.

Throughout my adult life, I've had the yearning to rub up against urban edges, avant-garde dissidence; from my first job as a bike messenger, to a post college attempt to work as a carpenter, a trip to west Africa, drumming lessons, wild horses in Galicia, bus rides in Mexico, etc., peoples and cultures and the puzzles of it all.

Though a wonderful high school teacher caused me to wish to grow up to be a French poet, an opportunity to learn welding helped me evolve into a sculptor of mismatched junk yard objects, rebirthed truck inner tubes and eventually musical sculptures that looked like homemade caskets. In the struggle to make structures that could stand on their own, I came to the realization that my body interacting with the materials was becoming part of the sculpture. The childhood of physical activity, fused with my quest to become an artist, as creating sculpture was inherently both a visual and physical activity. There I was carrying a 30 ft ladder through the woods in order to make a site-specific sculpture, when I realized that this awkward struggle was actually the crux of the art. A video camera felt like a perfect tool to extend the body, to collect the eye, for this hybrid performative practice, aspiring to become a living sculpture.

I say I make art for the situation, as both a nod to The Situationists (and dada folk) whom I identify with, but also to open myself to conceptual conundrums and controversial topics that I want to express through the medium of art. Like espresso gets pressed out of toasted beans.

2) What’s your creative process like?

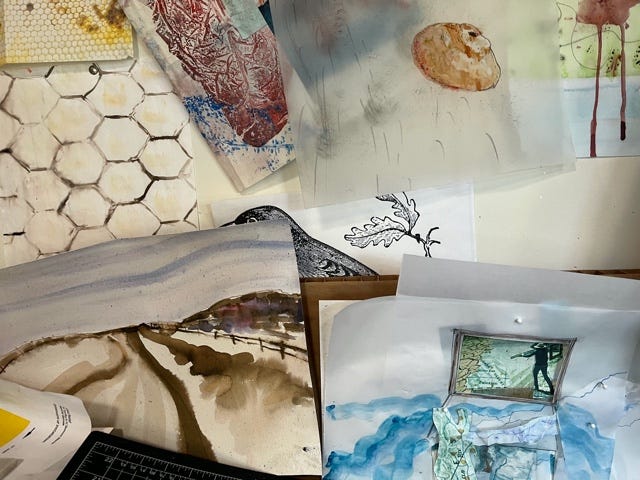

My current home art studio has been called an alchemy lab; it is definitely a zone of experimentation and materials colliding. It contains an archaeology of appreciated moments, as well as copious miscellanea from a bin of orphan hardware, to bicycle inner tubes, beeswax, a pair of headphones concocted of sea sponges. It's hard to describe here—because art is really my way of living in the world, the activity absorbs wildly and processes like a big tummy of thinking and doing that I monitor and digest.

When I watch bees in the garden, I feel very much in tune with that as a model for my art-making routine. Bees gather nectar visiting from blossom to blossom, back in the hive gradually transforming some of that nectar and pollen into honey, into nourishment. Like bee activity, my art making can require a lot of small visits to work through the kernel, a bit of thinking while fiddling or tinkering, it can take long time for a thing to find its form. My studio time is a mix of vigil, play, labor and most importantly, a kind of internal listening, a receptiveness to art happening with or without my help. The hope for a, perhaps trance, a still point in the churning world, a brief understanding, a new connection.

Meanwhile, drawing is a constant palimpsest of communion with my unthought thoughts and untamed metabolic energy. Why I still love to draw, is that I'm rarely trying too hard.

3) What puts a damper on your creativity? What do you do—if anything—to remedy that?

The damper to creativity can be the familiar reality of how much time it takes to just feed the human I'm attempting to be, let alone to pull off the (completion) of ongoing creative pursuits. The rollercoaster of this (little me—who?) in a profession that requires a ton of self-motivation meted out amidst existential and financial dread. “Hang on. Do some pushups. Go for a walk! Look under a rock!” There is, thank heaven, the practice of noting that when one thing is stuck, you can fly over to a different area of work and oftentimes a solution is sitting there that wasn't graspable last week. Art helps me live in a flexible way because it is not an equation. It is a solution finding steering wheel fluid.

Writing can help to clarify, because it is a form of gluing down my own thoughts for at least a post-it note moment. Over the years, while it has not aways been feasible to have a physical art studio during various chapters and towns of my life, it has at least been possible to have a pen and a notebook or typewriter (which was my favorite tool due to the muscular rhythm). Add reading (magpie style) as a co-mingling of the in-between, a creator of sparks. Rarely is it art that I’m reading about. Oh, wow look—poooof—the "damper" to creativity is long since forgotten . . .

And probably most key to my long-term resilience in this art profession are my wonderful artist friends!

4) Does age factor into your creative process, and if yes, how?

Age has been providing me with a sharper knife to cut with, one line instead of four?—along with a more humble-pie of expectation pedestals. An ability to shift the overwhelm into small gratitudes. I also can contribute more time to the deliberate nurturing of art community, having other people to test out ideas with; for artists to develop work not in a vacuum takes courage and accountability that I think improves all of our productivity. Through inner and outer dialogue, we progress. I'm currently part of Critical Ground, a group of four visual artists as well as our nascent group of artist writers, (WWW women who write?). If we were acting smartly as a species on this earth, we would honor and protect the wisdom of age, so I try to take that approach, like an oldening elephant scooping up and showering love, when possible, but also listening to the kids with big dusty ears.

5) What are you working on, currently, and what’s inspiring it?

These days I’m in Podcast production mode for The Department of Homeland Inspiration [see link in Soundings, below], a place created to house and share joy, wonderment, absurd commentary etc. without having to wait for some art professional to grant me access to an audience. I want this project to be an extension of the oral tradition.

I’m also working on a "land art" project with a colleague, Nanette Yannuzzi-Macias, whom I’ve collaborated with for over thirty years. The residency project, based in King City, takes on the richly complex topic of the Salinas River, an underground river. Just thinking about that fact is fascinating, let alone the water resource management involved in feeding millions of people, alongside a sea of wine grape investments, not to mention the pre- Treaty of Hidalgo history of the region as part of Spain/Mexico, Missions, Land Grants, etc.

6) What’s your favorite imperfection?

Darn it, when it’s other people’s imperfections, they always seem to become irritations, but I can practice tolerance on my own self, and cut her humor and slack! This describing myself as a bee (Melissa in fact means honeybee in several languages) moving from flower to flower, to wagging dances of excitement, also indicates that I routinely leave bits of unfinished business around. Things may coalesce into something "done," but often they won’t. And bees are so lovely, as they softly visit blossoms throughout the living world in fuzzy sunshine. So, I look to them as a not harsh way of noting that—whew, Melissa can be all over the place, easily distracted and pretty inefficient. But I can transform the scatteredness into something, or let it go, more easily if I meditate on the bees. Consciousness is time consuming.

BIO

Melissa Smedley is a multi-media artist activist who works in sculpture, video, performance and written word – creating what she calls “Art for the Situation.” In so doing, she aspires to be a living sculpture.

Since 2010, she has been operating The Department of Homeland Inspiration currently in Podcast format. Here, Smedley serves as the “The Art Ranger.” She specializes in the discovery of “art” in daily life, performs essays, and features commentary on various absurd conditions and delectable finds from the public domain.

Most recently, she was involved in Courage Within Women Without Shelter and the group, Critical Ground, comprised of Dora Lisa Rosenbaum, Amanda Salm, Denese Sanders, and Smedley. They engaged with homeless women in the Monterey Area, teaching a series of art workshops with the women and a subsequent exhibition of their art findings at Monterey Museum of Art (January 2022).

She is currently immersed in Land Relief, a collaboration based in King City with collaborator Nanette Yannuzzi Macias. This video installation project will unfold over the next year at Lesnini Field with California artist Erik Bakke who opened this unique artist in residency on the banks of the Salinas River. "A secret wild garden, it is 55 acres of wild land being both preserved and used for contemplation, research, and the creation of art.”

Smedley grew up in Denver, Colorado, received her undergraduate education at Brown University, and her MFA at UCSD. She has lived in Monterey County since 2007 with her spouse and two children, and several active beehives.

For the past decade as Artist At Large Consulting, she has been specializing in Public Art in affordable housing communities; “more art to more people” as she calls this coordinating work.

Performances:

Mad 2 Go

Installation: Perishables

LINKS

The nearby Salinas River is the largest underground river in the U.S. This article is from 2012. There have been a lot of challenges to maintaining the Salinas River watershed for one of the most productive agricultural regions in the U.S.

The Secret Life of Bees! From National Geographic Wild:

All about Art Hives. And a Portrait of an Art Hive in Montreal:

SOUNDINGS

The Art Ranger’s Department of Homeland Inspiration podcast, “Essayettes about the accidental beauty and often absurdity of being alive.”

Korean American vocalist Todd Park Mohr (of Colorado-based Big Head Todd and the Monsters) singing Black Beehive, in remembrance of Amy Winehouse:

Un Canto Por México, with Natalia LaFourcade and many musicians:

Thank you for visiting Eulipion Outpost. More next Saturday. Check out my Ko-fi page!

I can hear Melissa’s literal voice in these words. Also, I value her art explorations being so connected to her family history and journey. You asked me these same questions and I lack the sense of familial history/connection she has- so it’s interesting for me to compare how these circumstances form us as artists and individuals. I think your questions could be used as an activity for any artist to perform, in tandem with reading those you post!