Human "community" to me is a two-faced angel/monster. It can be life-affirming and supportive; it can be crippling and abusive—or worse (just take a look at social media). Yet in many ways it's necessary. Involved, uninvolved, taking a step back, or toward, I'm always wondering which Janus face I'm seeing.

A little background: My upbringing was unlike that of most Filipinx I know, with their large, traditional families. An only child raised by my independent-minded mom, Trinidad—we were a community of two in a post-war white, working-class neighborhood in the 50s-60s. My Dad, Nick, worked for the merchant marines, and would return home for about a month, twice a year. Most of the time he was gone.

Without his presence, and with no other close family around, we became hyper self-sufficient. I was a latchkey kid while mom worked at the cannery or the hospital laundry. When she was out, I’d climb the backyard fence to the roof, and enjoyed that vantage of the neighborhood from my perch (until a neighbor “ratted” me out). I was good at amusing myself.

This all changed in my teens when my mom started joining Filipino community organizations. Suddenly there were “aunties” and “uncles,” messy relationships, and other people’s kids I had to be “nice” to when I didn’t want to be.

I learned to serve guests, put on make-up, and worry about how I looked. I had to “behave,” and learned there were standards to which a young Filipina should hold herself. It was stressful, and it was my first introduction of Filipino-style community and extended “family.”

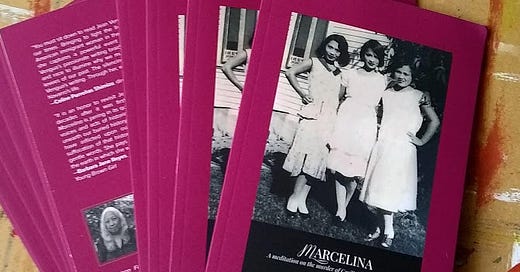

Maybe this was simmering subconsciously when I wrote the long (experimental) poem, “Marcelina,” published in Babaylan: An Anthology of Filipina and Filipina American Writers anthology in 2000, and republished (revised) in chapbook form by Paloma Press last year. It documented a story of a Filipino community in the 1930s gone bad—in the worst way.

Marcelina lived with her farm laborer husband in California during a period when Filipinos were frequent targets of racism. The pressure for Filipino women to “be good,” “feminine,” and “represent” the Filipino community could be unrelenting. Marcelina was deemed to be an adulteress and was brutally murdered by her community as punishment (the true motive may have been revenge for “betrayal,” when she testified in court to an act of abuse by a male neighbor).

So the book tackles an unpleasant subject, brown-on-brown violence. It’s not a “pleasant” read; there’s no balm of nostalgia, no comforting view of community. It raises a lot of questions—and not just about an “anomalous” historical incident.

As I read about the treatment of OFWs (Philippine overseas foreign workers), the abuse they endure, the pressure that the Philippine government, family, and the Filipino community place on them—especially women—to act “heroic,” to behave and “represent,” I know this is an ongoing issue, abetted by centuries of colonialism, contemporary economic pressures, and dictatorial, patriarchal rule.

Last year, a documentary film about Marcelina’s murder, The Celine Archive, directed by Dr. Celine Parrenas Shimizu, screened in film festivals, winning several awards. Look for it in film festivals this year, too. I read a few excerpts from “Marcelina” in the film, and met Marcelina’s family; wow. It was an honor to be part of this project.

Here’s the Celine Archive trailer:

Of course, the idea of “community” as “two-faced” is an over-simplification. It’s all more complicated and nuanced than that. I acknowledge that I’m a member of (sometimes outsider to) multiple communities, as an artist, writer, Filipinx, and older person. I even co-chair a nonprofit that promotes the historic preservation and community programs for a local, blighted, Chinatown, home to Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Mexican, and other minority groups for over a century. As an introvert, I don’t always feel comfortable in that role, but I do think communities can do good things that a person can’t always manage on their own—you just have to watch your back.

Hey, if you have an opinion, I’d love to hear about it.

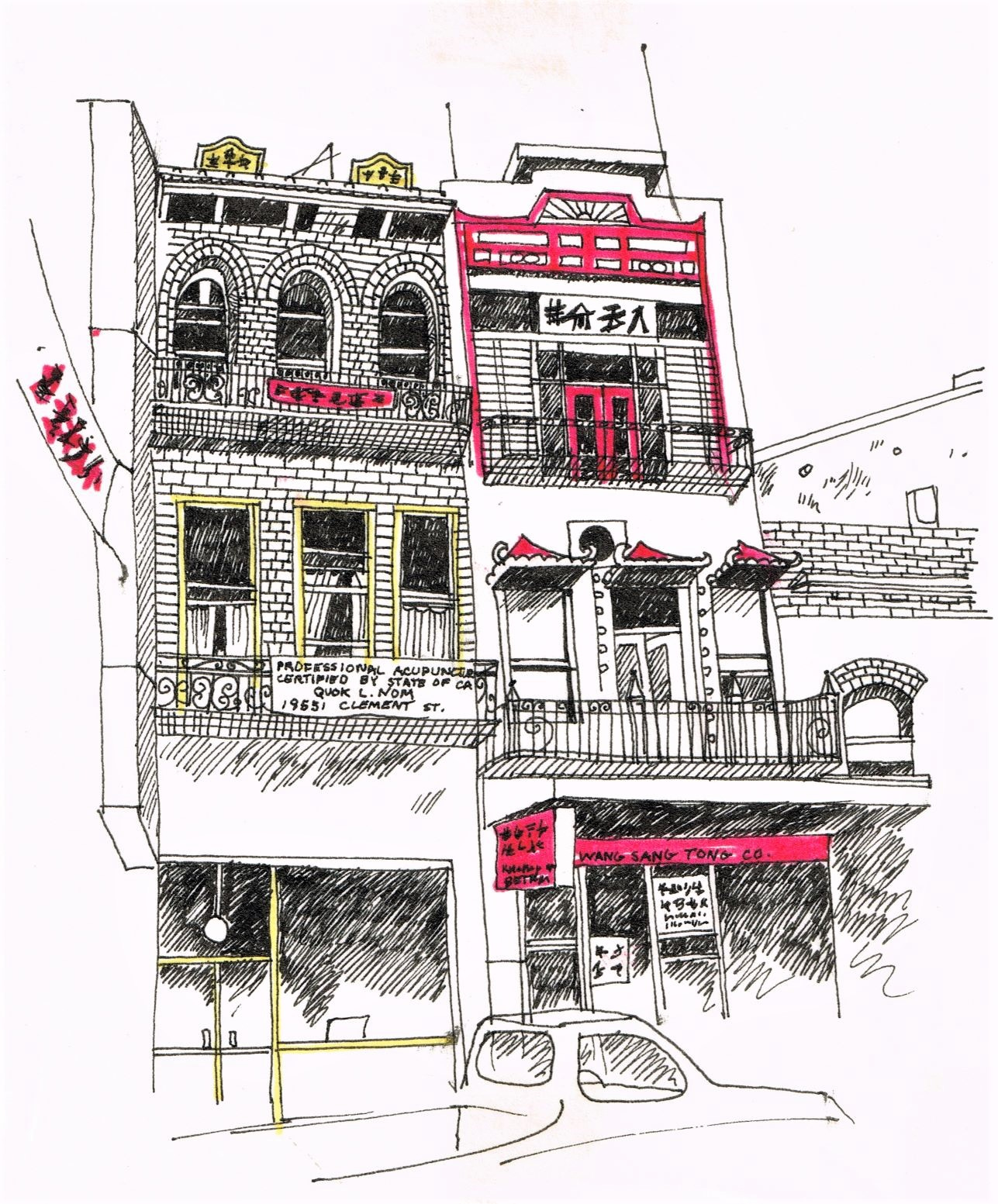

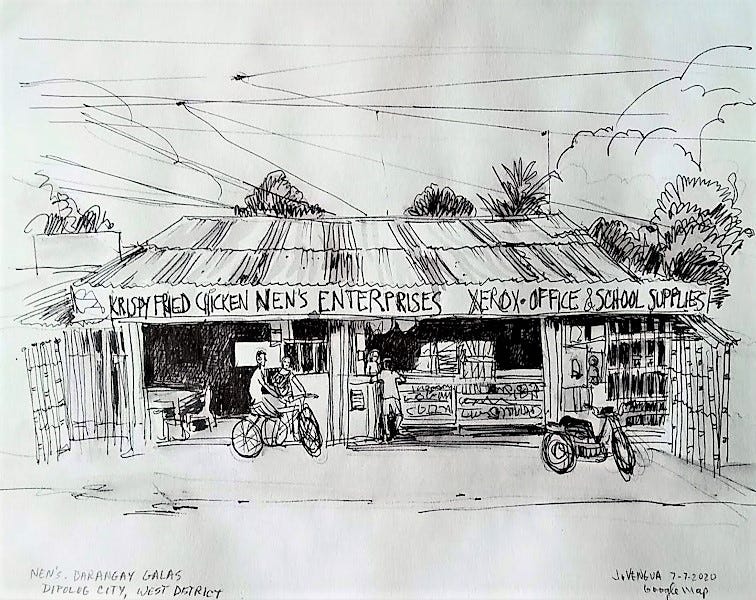

Drawings:

Sometimes, in the midst of this lengthy lockdown situation, I scan through Google Maps, looking at the neighborhoods or barangays (village or district) where my mom or dad once lived, wondering about how their childhoods growing up in the Philippines were different from mine. These were/are communities, too. I notice the ubiquity of sari-sari “variety” stores: those little stands—often run by women—set up in front of family homes or on street corners, where they sell everything from single-use items like toilet paper rolls, shampoo, beer, or pastries, and which also serve as local hangouts. They’re fun to draw. I notice there are even U.S. versions of these little neighborhood stores. Thinking of doing a series of these drawings.

I sketched the drawing, below, while sitting in a car parked at Portsmouth Square, San Francisco Chinatown:

Video:

Theaster Gates is one of my “community” heroes. Check out his video, “How to revive a neighborhood: with imagination, beauty, and art.”

Dawn Mabalon was a historian, community activist, and friend who passed away several years ago. Here’s a video remembering her, and her passion “For Community, for Culture, for us. Dawn Mabalon is in the Heart.”

All about the community of Little Manila, Stockton, CA

Podcasts:

I always enjoy the Art Ranger’s Department of Homeland Inspiration podcast, with its humming, rattling, echoing, and harmonica sound effects, a poetic commentary on art and life in this crazy-toon world. She is herself an artist, performer, and cyclist. One of my favorite episodes is POWERAMA which aired soon after the recent election.

Please subscribe to Eulipion Outpost—It’s FREEEEEEE!

See you next week…