7/24/2021

Meteor, Winslow AZ, Instagram videos, oak charcoal, erasers/erasures, borders, rubber plantations . . .

7/24/2021

For my next birthday (a few months away), I and my partner will be driving across the desert to visit a vast empty space that was hit by a meteor during the Pleistocene period. It’s located near Winslow, AZ (oy, now that song is running through my head). Here’s a cover of the song I’m thinking of by some kababayan—happy backyard jamming (and drinking) at its best in the Philippines:

“Take It Easy” (by The Eagles), cover by Inuman.

And if we don’t get fried in the Mojave, or get smoked out by one of California’s many forest fires, I predict we’ll have a slightly disturbing yet pleasant experience around this great vacancy, this impression left by a gigantic rock, “debris” from some huge object whose rough skin began to unravel and distribute itself outwards towards other galaxies and planets, including our relatively tiny “earth.” I’m looking forward to the trip.

In other news, Adam Mosseri is talking about Instagram’s prioritizing of video over static photo sharing.

I gotta bad feeling about this. I can see myself spending hours trying to figure out how to create and post short videos to the Instagram’s increasingly clunky interface, just to help them catch up to their competitors and finally defeat them in the global war of the CEOs. In the meantime, all the art images and videos I would often “discover” in the Instagram search engine have become inter-species (dog/cat) snuggling and wide-eyed kitty cuteness. I know this because I constantly get waylaid by these videos, and this is not good. This is distraction. This is working for the man.

So let us go to the world of bricks and mortar, flesh and weeds, trees and carbon, ink on paper (and erasers):

ART

In the 7/17 issue of Eulipion Outpost, I wrote about graphite (carbon) and the invention of the pencil, and included some videos by artists who use carbon in interesting ways. Even with the focus limited to just graphite and pencils, there was so much more I could’ve added—it’s a huge topic—but it would’ve been a bit much for a newsletter.

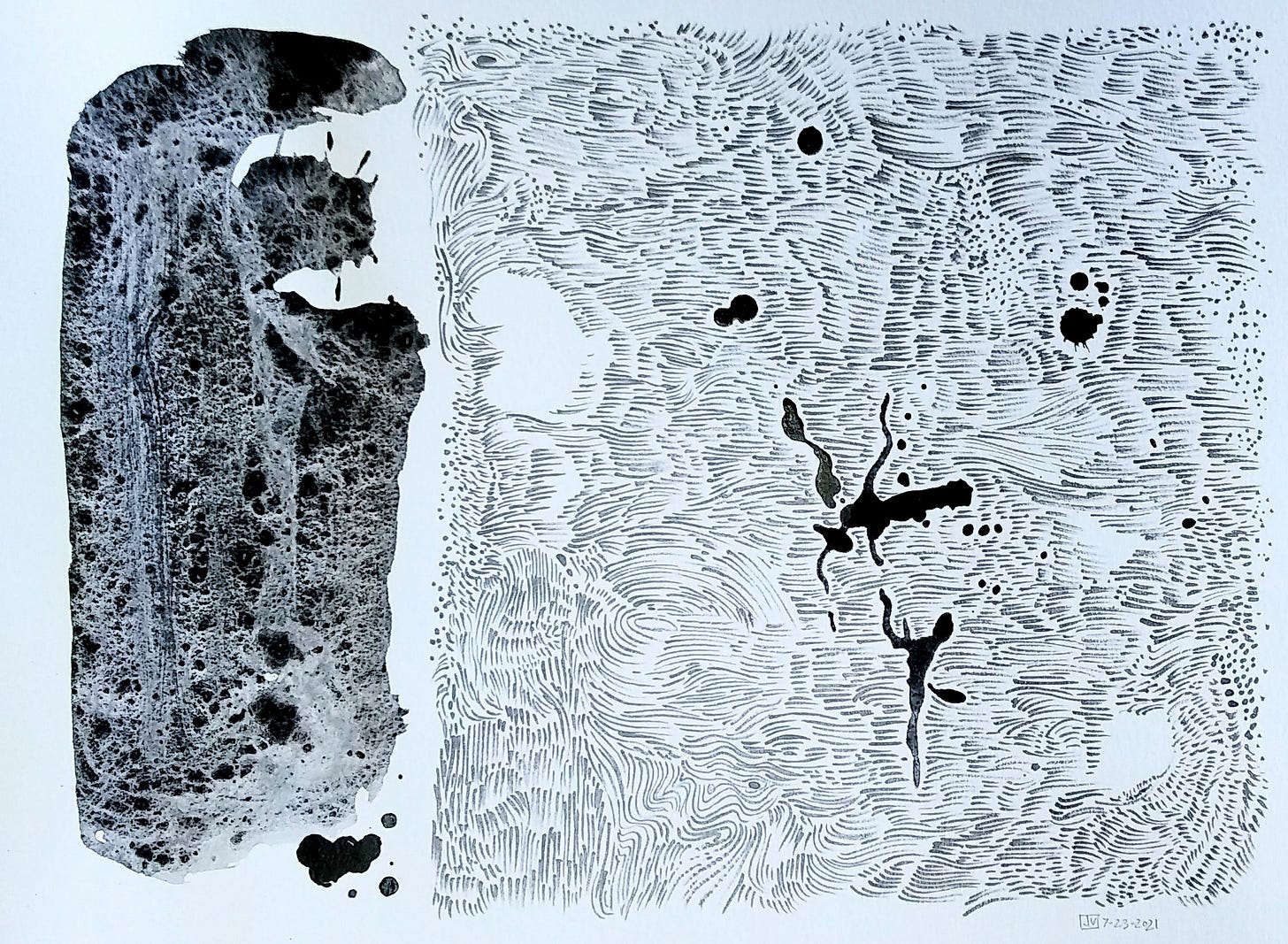

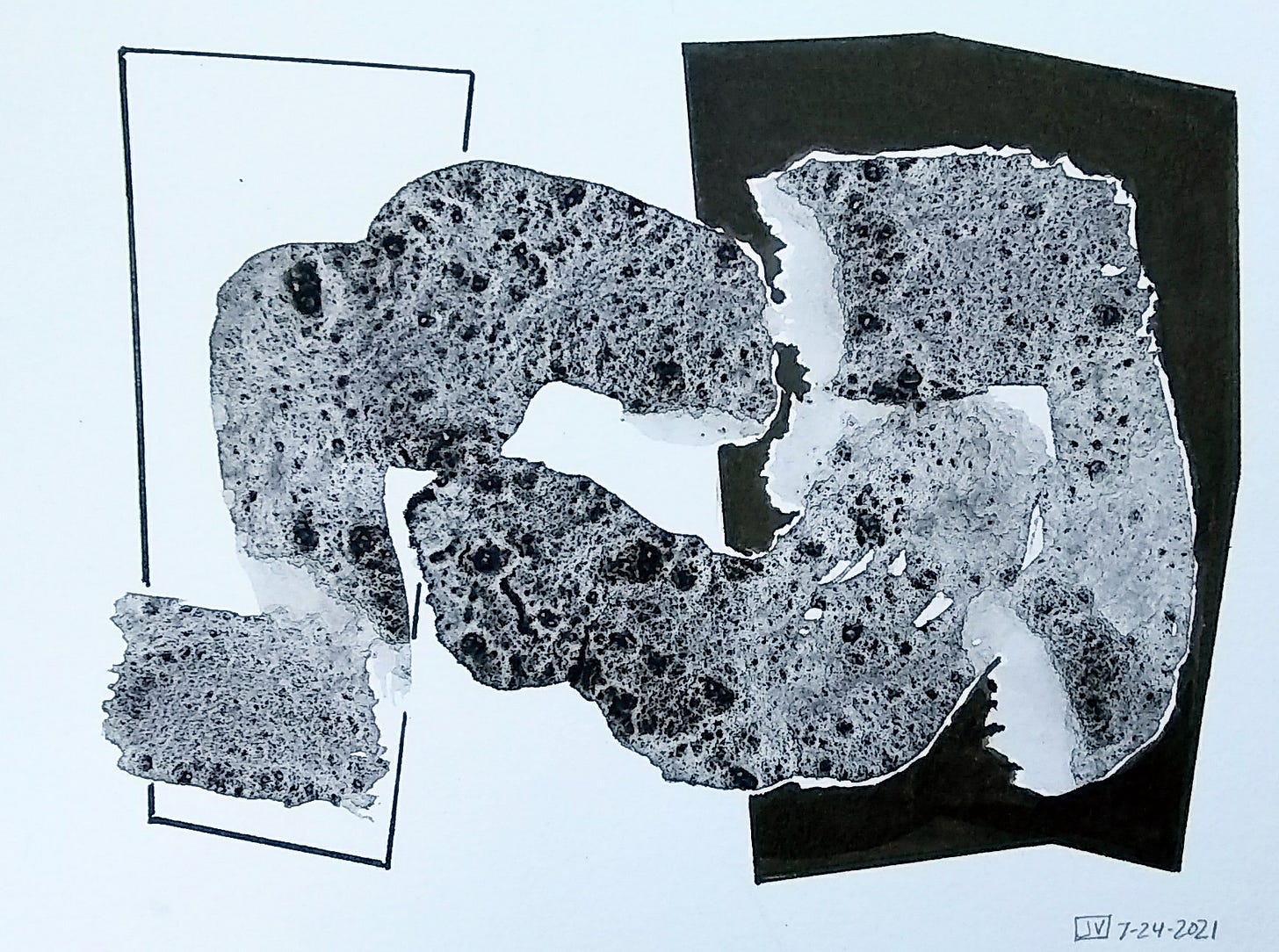

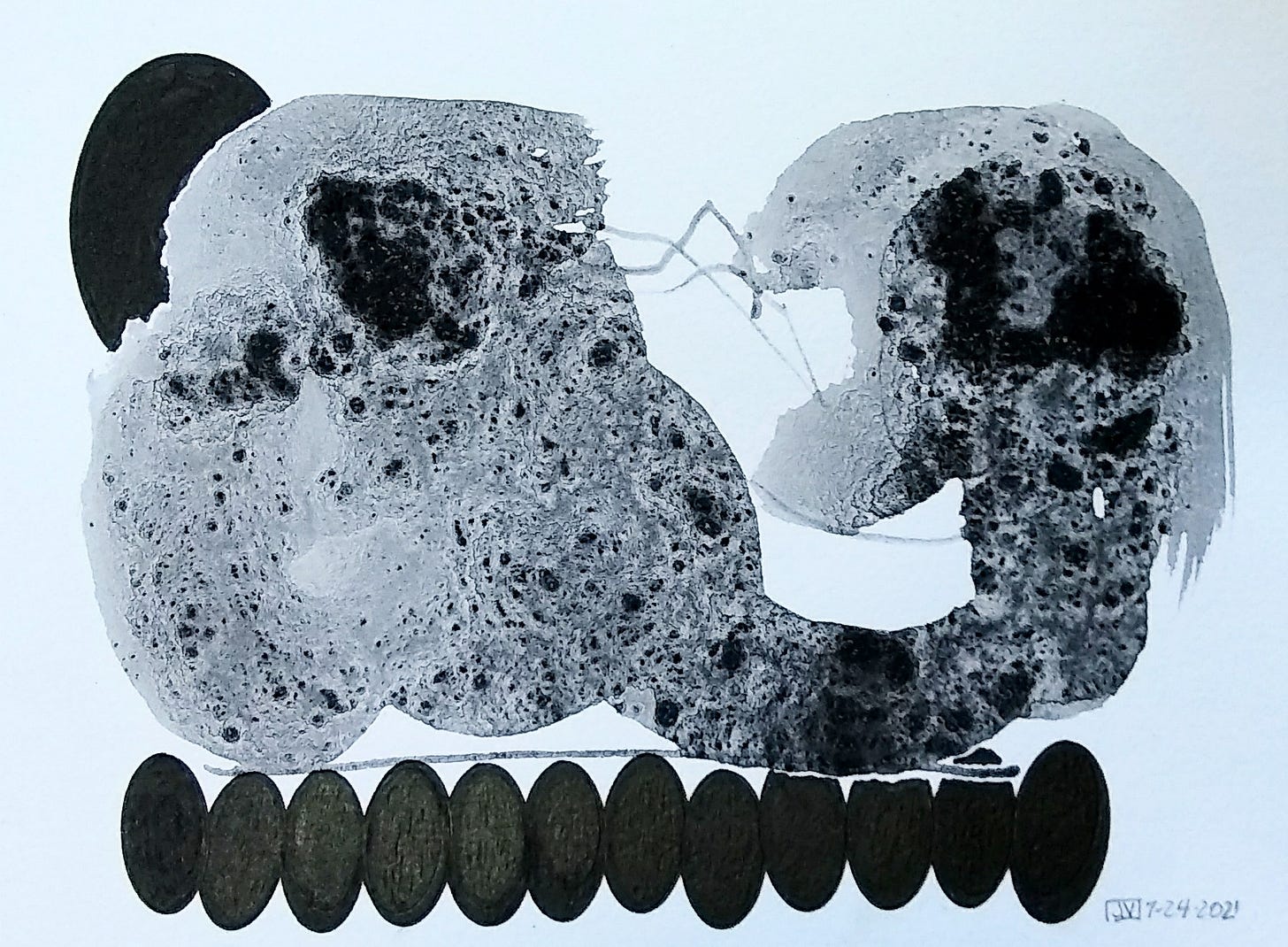

Still, I thought I would at least get a little closer to the subject if I took some carbon I happened to have, in the form of carbonized (burned) oak twigs, and ground them down to make an ink. So I bought a mortar and pestle and proceeded to do just that.

I mixed in some water and gum Arabic, then painted the stuff on watercolor and mixed-media paper. The effects produced were really interesting. I combined them with some ink work.

There was a problem, though. Perhaps because I didn’t ground the stuff finely enough; the paintings “shed” some of the larger charcoal particles, making storage (not to mention framing) kind of iffy—even after spraying it down with several layers of fixative. I’ll need to experiment with the amounts of binder I’m using, or change it to something else. Maybe I can make prints out of these. In any case, it was fun.

If you’re in town around July 30, stop by Other Brother Co. (877 Broadway Ave., Seaside, CA), grab a beer, and check out the art opening there, sponsored by EAAM and Other Brother Beer. This is EAAM’s first art show since the pandemic began. “Crossroads,” which I posted in the last issue, will be on exhibit there (and for sale) along with wonderful works by local artists.

ERASER

Next in my series on art tools: the eraser. I was seriously considering “the pen” or even “ink,” but will save those lengthy topics for another time. Besides, what’s a pencil without an eraser?

First—bread. Before the eraser, bread was used to erase pencil marks. I admit to considering this as merely an amusing historical anecdote. But Musashino Art University in Japan takes bread seriously as an art tool. They even provide photographs showing the proper way to hold a piece of bread while applying it to paper.

. . . cloth and bread can be used to correct lines and make fine adjustments to the amount of charcoal applied, enabling delicate expressions. These erasing tools have the advantage of causing the least amount of damage to the charcoal paper on which the work is drawn.

The most suitable type of bread is ordinary bread that does not contain much butter or oil. Bread containing oil should be avoided as it could leave stains on the paper. A suitable amount should be taken from the soft white parts of the bread, not the crust. Knead the bread softly, shape it into any shape you want, flat or pointed, and use it to change details and remove charcoal to add highlights, etc. You can also press the bread against the drawing without kneading it or rub it gently over the drawing to produce subtle changes in tones. (https://art-design-glossary.musabi.ac.jp/charcoal-drawing-erasing-tools-bread-cloth/)

Clearly, sourdough (sans olive oil) would make an ideal eraser. And it just occurs to me now that I could use bread to pick up the extra charcoal bits that are not adhering to the paper in my drawings (see above).

In 1770, scientist Joseph Priestly (who discovered oxygen) noted the erasing qualities of a “vegetable gum” called “caoutchouc,” but which he called “rubber” because it could be used to rub out unwanted marks.

As I mentioned in the 7/17/2021 issue of this newsletter, graphite at that time was a holy mess to use. So imagine a piece of sheepskin wrapped around a chunk of graphite and trying to make marks with that awkward thing. You’re going to need something to wipe or rub out the mistakes.

“Of course, rubber ended up having a lot of other uses besides erasure. Ancient peoples from Mesoamerica were using a latex material culled from trees as balls for sports (Dorothy Hosler, et al., “Prehistoric Polymers . . .” ). Columbus found indigenous peoples of Haiti playing a game with latex balls (Charles E. Carraher. Carraher's Polymer Chemistry, eighth edition, 302).

Later in 1615, Spanish writer Torquemada reported that Haitians were using the substance to make footwear and “bottles” (Christopher Cumo, Ed., Encyclopedia of Cultivated Plants, 904). . . .”

Anyway, the resource (later called rubber), as so often happens, was taken up by the British and Dutch for colonial trade (see more about the effects of that trade, below, in “FOUR” (links).

Like Nicolas-Jacques Conté, who patented the pencil, Edward Nairne was an inventor; among other things, he invented an electrostatic generator for “medical” use and the marine barometer. Nairne capitalized on “rubber” as an eraser, and his associate, Priestly, backed up his findings. Enterprising Nairne cut the rubber into small blocks and sold them for several shillings each.

Since Nairne’s rubber erasers didn’t last long, someone needed to improve on them, and that someone was Charles Goodyear. Yes, that Goodyear. Long story short: vulcanization worked wonders. See also Megan Garber, “Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Eraser Technology” (Atlantic).

FOUR

You knew I was going to get to this, right? I’m not going to shy away from it. “The War for the Amazon’s Most Valuable Trees”—rubber trees. By Vox.

Jet Pens has a good overview of erasers as a modern tool, and what you should look for in a good eraser. These days, they don’t always have to be made of rubber.

“How Art Allowed Me to Erase Borders,” a Ted Talk by Anna Maria Fernandez:

Testing 30 Artist Erasers – which one is the best? Kasey Golden does all the research for you:

“Erase and Rewind” (Cardigans) cover by Veronica Monaco:

I didn’t make the deadline. As I write this, it’s 12:39 a.m. Oh well…

ERRATA

Alas, I noted errors in para. 8, under “ERASER.” The paragraph was previously written as follows:

“Of course, rubber ended up having a lot of other uses besides erasure. According to reports from Christopher Columbus, South American Indians and Haitians were already using rubber for sports and footwear when he arrived on the scene (Britannica.com) . . .”

This has been corrected (in the website version only—not in the email) to:

“Of course, rubber ended up having a lot of other uses besides erasure. Ancient peoples from Mesoamerica were using a latex material culled from trees as balls for sports (Dorothy Hosler, et al., “Prehistoric Polymers . . .” ). Columbus found indigenous peoples of Haiti playing a game with latex balls (Charles E. Carraher. Carraher's Polymer Chemistry, eighth edition, 302).

Later in 1615, Spanish writer Torquemada reported that Haitians were using the substance to make footwear and “bottles” (Christopher Cumo, Ed., Encyclopedia of Cultivated Plants, 904). . . .”

Anyway, the resource (later called rubber), as so often happens, were taken up by the British and Dutch for colonial trade (see more about the effects of that trade, below, in “FOUR” (links).

As always, I welcome friendly comments:

If you liked what you read, please share. If you haven’t subscribed, please do—it’s free.