Bloody Mutiny, Public Folly

#161: Seafaring Life; Bloody Mutiny, Public Folly; Moath al-Alwi, Gener Padugo, Wawi Navarroza, Christina Lopez, Ronald Ladouceur, and Greg Gannon; Anne Darby, Kuerdas, and Javier Santiago.

THEN & NOW

Seafaring Life

When I was a kid, and even after I became an adult, I took my father’s seafaring life for granted. It was just a job that happened to take him away from home a lot. I was an only child, involved in my own little world; I didn’t think much about what a job like his would involve, or how it would shape his thinking or his relationship with my mother and me. I didn’t know that seafaring was a way of life for many Filipinos, because the Philippines was strategically placed for trade with Asia, and later Europe and the Americas.

Nowadays, while reading my father’s letters, I’m often struck by how all-encompassing the seafaring life was for him and also his closest friends—both of my godfathers worked and traveled on ships—and what a huge impact it had on our family in the U.S. I recall a day when Dad (who, by then, had retired from shipboard life), Mom, and I were preparing to leave the house. Dad stopped just before we closed the front door, turned around, and asked if we had remembered to “secure the hatches.”

Perhaps some part of him was still at sea.

Philippine seafaring culture is rich with symbolism and myths; the Philippine national and regional languages have many words and phrases describing the sea and its vicissitudes. After all, the Filipino name for a village is “barangay,” which comes from “balangay,” a boat. Boats are thought to possess a soul, “fundamentally related to the tree used for its construction.” The kibang (or guibang) ritual consults a sea spirit to foretell positive or negative outcomes through reading the rocking motion of waves against a boat.1 Some ethnic groups, especially in the southern parts of the archipelago—live most of their lives on boats, and in wooden houses built on stilts over the sea, close to shore.

But there have also been dark chapters in this seafaring history (like the one I describe below), especially in relation to trade. Filipinos have experienced piratical attacks and have themselves have been pirates. Some Philippine tribes developed deadly sea-warfare skills as protection, while others retreated from the coast to the hills, or became nomadic. Colonizers recognized the Philippine natives’ seafaring and boat-building skills, but colonization and global trade has also brought slavery, indentured servitude, and low-wage jobs.

Bloody Mutiny, Public Folly

I have occasionally come upon evidence of how Filipinos—in the form of the mysterious “Manilla Men”—made their way into 19th century Western literature and print culture. They are mentioned in novels and essays by Herman Melville, William Dean Howells, and Mark Twain; in a diary entry from September 28, 1841, Nathaniel Hawthorne briefly mentioned sharing a birthday picnic lunch with friends, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and two Manilla Men. From his description, they may have been mixed-heritage, Spanish-speaking Filipinos:

I ought to have mentioned among the diverse and incongruous growths of the picnic party our two Spanish boys from Manilla—Lucas, with his heavy features and almost mulatto complexion; and José, slighter, with rather a feminine face—not a gay, girlish one, but grave, reserved, eying you sometimes with an earnest but secret expression, and causing you to question what sort of person he is.

—Nathaniel Hawthorne

During the late 19th century, and especially when the Spanish-American war began (1898), American newspapers published articles by writers—such as Lafcadio Hearn—to write about Filipinos and Philippine culture.

While looking for references to Filipino newspapers in the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America site, I noticed a “true story,” written by Arthur Conan Doyle, about a bloody mutiny conducted by “six Manila Men” on a British ship called The Flowery Land. “The Deed of the Six Manila Men” was published in the Omaha Daily Bee, March 29, 1899.

In the same year, it was also published in the Philadelphia Inquirer as “True Story of the Tragedy of the Flowery Land,” and in the San Francisco Call as “Mutiny of the Flowery Land.”

Yet, the mutiny had occurred decades earlier, in the mid 1860s.

The Flowery Land,2 a British clipper, had been heading to Singapore with a cargo of baled cotton, iron pipes, bottles of champagne, and other wines. Its crew was diverse, speaking many different languages. This, Conan Doyle noted, was an example of how “the British seaman was being elbowed out of existence.” As usual, for those times, characterization of the Manilla Men was racist, underlining the idea that the crewmen were considered untrustworthy by nature:

“The Manila Men appeared to submit to discipline, but there were lowering brows and sidelong glances that warned their officers not to trust them too far. Grumbles came from the forecastle as to the food and water—and the grumbling was perhaps not altogether unreasonable.”—Arthur Conan Doyle

The story had all the elements of a good pirate yarn: There was the supposedly “jovial, genial” British captain, John Smith, and his younger brother George. Their stern first mate, Karswell, felt that the crew had a bad attitude and needed “thrashing,“ for there was “hardly an Englishman aboard.” Finally, there were resentful crew members (described as “half Spanish, half Malay” Manilla men) who carried out the bloody mutiny.

At their trial, the mutineers later claimed that they had been slapped and punched, that food and fresh water had been withheld, and the captain had suggested that they drink salt water instead. The first mate had punished one of the men for being sick by lashing him to the mast.3 In retaliation, they murdered the captain, stabbing him to death, and beat to death the captain’s brother and the first mate. They then selectively forced other crew members—including the Chinese cook—into the sea.

Since the second mate, Taffer, was a good navigator, he was forced to steer the ship to Uruguay. Their one mistake was in allowing Taffer to live. Once within sight of the shore and Montevideo, the mutineers dropped the small boats and scuttled the ship; then, they rowed to land, and split up with the intention of disappearing and evading arrest. However, Taffer went straight to the local police, who managed to capture the mutineers and sent them back to England, where they stood trial in London.

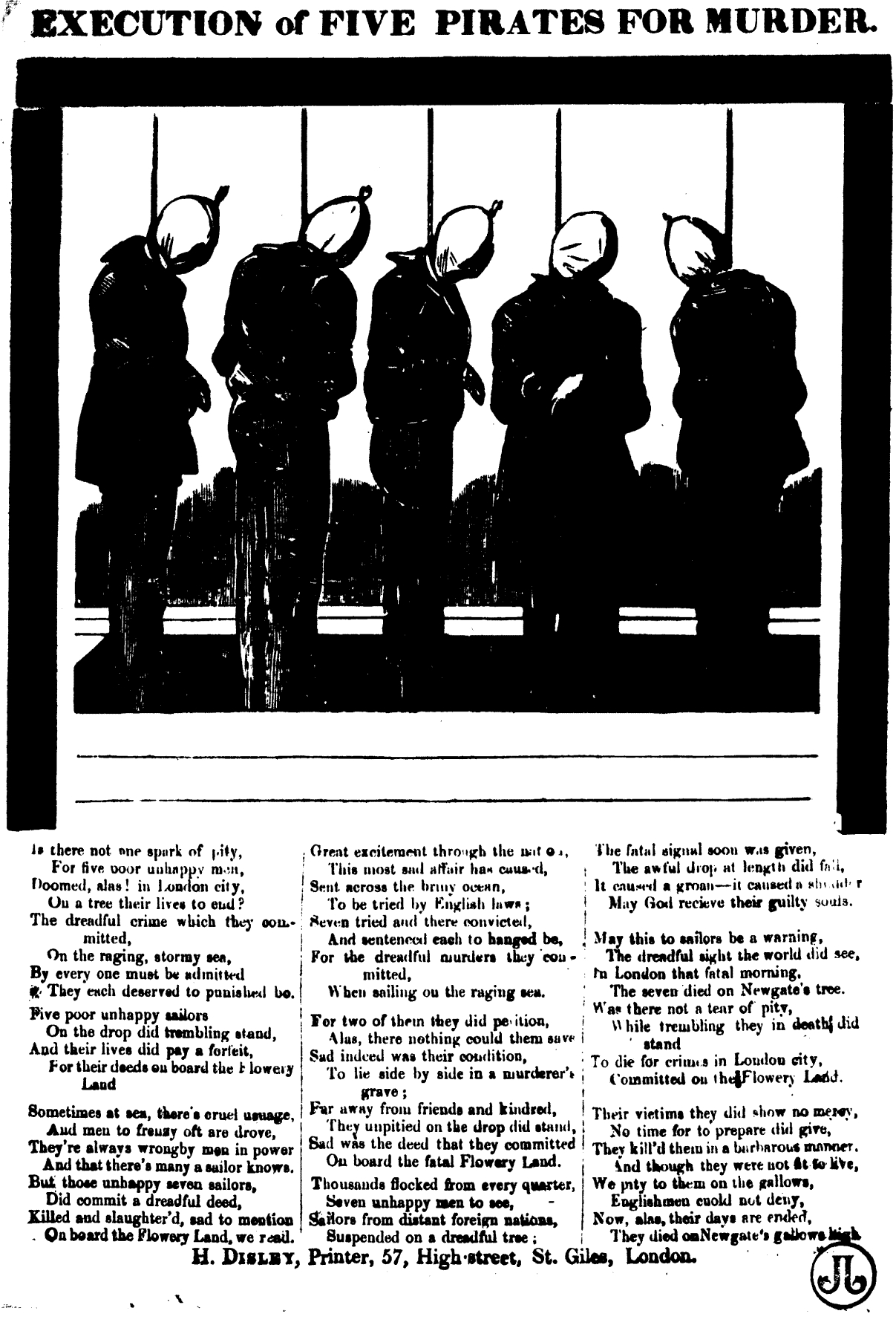

The trial occurred in July, 1864. Eight men were tried: John Lyons (or Leone), Francisco Blanco, Ambrosio Duranno, Basilio de los Santos (sentenced to life), Marcos Watto (of “Turkish” origin), Miguel Lopez, and the brothers Marcelino and George Carlos (both of whom received lengthy prison sentences). Five—Lyons, Blanco, Duranno, Watto, and Lopez—were condemned to execution by hanging at Newgate Prison, before an “immense” crowd (about 20,000 people, as reported in The Age, Melbourne).

The story, published in the U.S. and other newspapers around the world, captured public imagination, possibly because the execution occurred during a period when the necessity for public hangings in England were being strongly questioned, to say the least. The public execution of the “five pirates” was the first to take place in London in forty years.

Poems were written about the condemned mutineers, printed on broadsides, and posted around the city. A few years later, in 1868, the British Parliament abolished public hangings.

Lengthy reports of the mutiny and execution were published in The Age (Melbourne, Australia), and the Otago Witness (New Zealand).4 In both newspapers, the execution was described in excruciating, voyeuristic detail. The Witness article went further to romanticize one mutineer—”the handsome, dashing Lopez”—while characterizing the crowd—many of whom had paid for private rooms in ale houses and hotels at strategic locations around the gallows to view the event—as lawless rabble:

On the pavement beneath were assembled, not merely the scum of the population, not the drabs and petty thieves who bandy ribaldry and pilfer deftly, but organized gangs of powerful, muscular ruffians, who hustled and robbed every wayfarer who had aught of which to be despoiled. —Otago Witness (author name not available)

This extremely critical perception of the witnessing crowd as “King Mob” was echoed by newspapers in England, such as The Standard and the Times. Reports of the “bloodthirsty” and “revolting” nature of the crowd nearly eclipsed the dire deeds and execution of the mutineers. Executed Today summarizes information from various articles focusing on the story.

I think it’s significant that this execution was reported globally, and emerged decades later as a “true story” written by the famed British author for U.S. newspapers on the eve of the nation’s first colonial conflict (the Spanish American war), followed by the Philippine-American war and colonial acquisition of the Philippines. Yet, the execution seems to have been mostly forgotten today.

I suppose I should now come up with some damning or philosophical conclusion. But I’m still thinking about how the execution played out, and its social and historical contexts: the apparent abuse, the explosive anger of the Filipino crew, the murders and mutiny; the British government’s decision to make it all public in the most lurid way possible; the newspapers’ voyeuristic descriptions—even while expressing their revulsion and criticism of the public execution—and finally, Arthur Conan Doyle’s “true story” of bloody mutiny on the high seas.

Perhaps you have some thoughts about it? Do let me know.

RABBIT HOLE

Boat building arts and traditions of the Sama peoples of Tawi Tawi, how the tradition is passed on, and how boatbuilding has changed through scarcity of resources:

Philippine fishers at work; it’s fascinating to watch them walk along the planks while launching smaller fishing boats off the mother ship on choppy seas:

Moath al-Alwi has been making ships while he is imprisoned at the Guantanamo facility, where he has still not been charged with a crime. Some of his creations have been exhibited in galleries.

Palawan native Gener Paduga, partnering with the Tao Foundation, built a Philippine traditional shallow-draft, outrigger sailboat (with a couple of low-tech modern elements) called Balatik, which he calls “my soul.” He uses it for tours and to educate the public about the seafaring history of the Philippines

A return to sailing makes sense—our marine environment is under threat and fuel prices are rising. Learning to sail again will help Palaweños escape dependence on gasoline and diesel while, at the same time, fostering a deeper understanding and respect for the sea. — Gener Padugo

Wawi Navarroza and Christina Lopez are contemporary Philippine artists who focus on self portraiture and identity in response to changing conditions, such as location, climate change, technology, and decay:

Independent scholar Ronald Ladouceur on ghost signs of Philadelphia. Similarly, Greg Gannon has been pointing out ghost signs in Baltimore. Does your town have ghost signs? Where are they located, and what can they tell us about where we live? There are certainly such signs in Monterey. And I’m wondering if there are ghost signs in Manila—but I suspect the tropical weather erases them pretty quickly. Such “hieroglyphs” are a great source of local stories!

SOUNDINGS

“Newgate Gaol” sung by Anne Darby. In memory of Anne Darby (née Wiseman) 1953-2016. Original composition. Written in 1975 and recorded at Sprint Studio, Somerset, in 2010.

Reggae and ska seem to resonate strongly with a lot of Philippine youth, and older folks, too; it’s another one of those cultural currents that have reached Philippine shores from other islands. Kuerdas performs “Lisang Bangka”5:

Jazz pianist and composer Javier Santiago performs “The Light That Awaits Us.“ With Giulio Javier (bass) and Michael Mitchell on drums. San Jose Jazz Break Room Session. Santiago will be performing locally at Wave Street Studios in Monterey, Sept. 17.

A big thanks to all of you who read Eulipion Outpost regularly, and to those who have subscribed here or donated on my Ko-fi page to support my efforts.

My ongoing appreciation goes to the Mysterious M. for his editing.

My website (under construction) and blog: Jeanvengua1.wordpress.com

My Links List is on an old-school Neocities site that I built.

Eulipion Outpost is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The “soul boat” quote and information about kibang and guibang are from Maria Bernadette L. Abrera, “The Soul Boat and Boat Soul: An inquiry into the Indigenous ‘Soul.’”

"Flowery Land” was a common nineteenth century term for China (https://crimereads.com/arthur-conan-doyle-and-the-mutineers/).

From Crimereads.com

Australians had a natural interest in this topic, since the country had served as a destination for exiled prisoners of the British penal system (and Australia was itself a penal colony) until 1868, as protests against that usage began to intensify.

My grasp of Filipino is not good, but it seems to be a song of solidarity, “Let’s join together; let’s paddle in our boat together…” I think the title means something like “the boat is leaving.” If you know better, let me know! Written by: Jason Ugbaniel. Album: Bugsay Ta Bay. Released: 2018

I enjoyed learning about boats having soul. The song by Kuerdas seems to have a mix of Tagalog and Visayan. “Let’s sail together, hand in hand, to the horizon of the future, a tomorrow of peace and success.”