Drawing Parallel Lives

#160: Drawing Parallel Lives, Art & Escape, Richard Steven Street, DrewScape, Revision, Hernan Diaz, Mongolian Contemporary Art & Mugi, PG Art Center's new exhibit, Andre 3000, & Steve Martin

THEN & NOW

Drawing Parallel Lives

I’m touching on some details that I’ve mentioned previously, because I keep learning more as I continue to go through the letters and look things up online. This newsletter is starting to feel like it’s growing organically, through overlapping layers, like leaves on the forest floor. Generations of research by others help to fill in the gaps.

On January 7, 1946, my mother wrote a letter to my father. Although she was still using U.S. Army stationery from Camp Murphy, where the family had been staying temporarily after the chaotic liberation of Manila, the address she wrote next to the Army logo on the first page was that of her beauty parlor at 2049 Rizal Avenue (once called Avenida Rizal), in the Santa Cruz District. She wrote to tell Dad that she hadn’t been able to answer his missive from Stockton, California, because she had been sick with a fever,1 and to give him the new address of her beauty parlor, just two blocks from the family’s new home on Misericordia St.

I thought you would be arriving [in Manila]. I do hope that you are coming soon. When are you coming dear? I just want to know it. You see, we have not seen each other for almost five months. I was disappointed when you told me you would be back again in Okinawa.

Their lives seemed to be running parallel, but not quite coming together yet—like Rizal Ave. and Misericordia St., before Chintown’s Ongpin street bisected and connected both.2

On January 25, 1946 my father addressed a letter to my mother at 2032 Misericordia. That Spanish colonial street name, meaning “pity” or “mercy,“ was later changed to Tomas Mapua Street, named after the Philippine educator, architect, business leader, and initiator of countless construction projects.

I imagine the Manila of my mother’s time, even just after World War II; the sections of the Santa Cruz district that survived likely still retained that mix of Spanish colonial and American faux (neo) classical and modernist architecture mixed with Chinese influences. The archipelago had emerged from centuries of colonialism, followed by the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars. Building on those culture clashes with characteristic abilidad,3 there were art deco theaters and modern shops on bustling Avenida Rizal. On the side streets and older areas, some of the traditional houses, bahay na bató (stone and wood houses and compounds), still existed, with their large, shuttered windows, closed in the afternoons to keep out the tropical heat.

Today, Google Maps reveals that Rizal Avenue (once called Dulumbayan or “the end” by Spanish colonizers4) and Tomas Mapua St. (Misericordia) were overtaken in the 1980s with the juggernaut urban construction and transportation projects of the Marcos dictatorship era. The architecture still has that authoritarian cement-block feel. Nowadays, Rizal Avenue parallels the elevated light rail line (LRT), which has turned the Avenue into a kind of brutalist tunnel, lined with shops, “optical clinics,”5 and vendors of everything from produce to mobile phones.

Both the “beauty parlor” (as Mom called it) and the house or apartment the family lived in were about twenty blocks from the corner of Ongpin and Tomas Mapua. Three decades later, that busy intersection marking the entrance to Chinatown was made famous by Lino Brocka’s film, Manila in the Claws of Light. Set in the early 1970s, the main character, Julio, comes from the provinces to Manila seeking work and his girlfriend, who is lost in the mazes of the city. Some of the film’s most disturbing scenes take place on construction sites during the 1970s, sites that dwarf and dominate, and even kill, its workers—just as the concrete pillars, cars, and overpasses dominate Rizal Ave. and Tomas Mapua streets today.

Below: a walking tour of Rizal Avenue at night (by KoiWander on YouTube)

The prologue to Manila in the Claws of Light (from Peter Kien'in Dram Atölyesi, YouTube), juxtaposes bits of old Manila with the ruins of war and gritty commercial vistas, as the LRT and urban renewal structures are being built. In many ways it’s a heartbreaking scene with no dialogue:

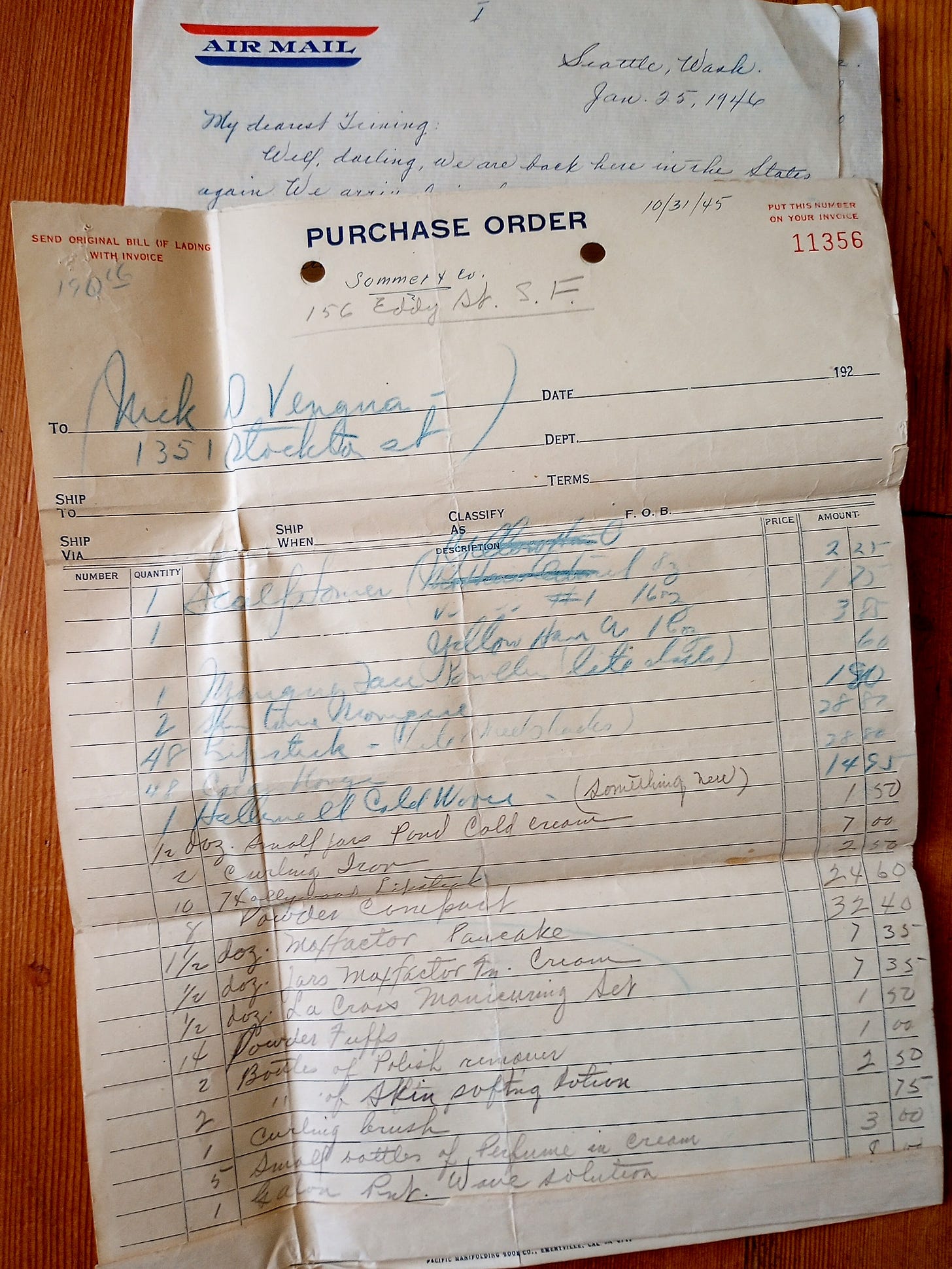

A purchase order bundled in the envelope with my dad’s letter shows that Mom’s plans for re-opening her beauty parlor were in full swing as early as October, 1945. Dad had purchased $190.06 worth of beauty supplies for Mom’s shop, which he calls “our” shop. But there was more:

What I bought for your own and for others I won’t attempt to mention it all here, for I want you to enjoy a little surprise. But here are some that I can name. [A] whole set of dinner wares [sic]—about ninety pieces all together. Set of silver wares. Some clothing, stockings, and eight pairs of Sunday and everyday shoes.

I’m a bit gobsmacked by the number of items he listed (there’s more on the back), as well as the cost—quite a lot for that time. Where the hell did he get that moolah? Add to that the risk of delivering it all by mail during a period when “shipping service for the public [was] not functioning yet,” many transport ships (including the one he was on) were being “retired,” suddenly, dashing his immediate plans to visit Manila, but also making long-term plans to ship goods unpredictable, while “the only people who [could] use shipping spaces [were] the big Firms who have Government permits.”

Dad went into more detail about the transport issues, and how he was determined to find a way to deliver—somehow! I figure he was also doing his utmost to impress my grandmother Matea, who was notoriously suspicious of men’s motives, and only too happy to kick them out the door if they didn’t meet her standards. He was going to prove his mettle to both her and my mother.

In spite of all our reverses . . . I won’t easily get discouraged now that I have you. You are my inspiration, darling. A man without an inspiration is just like a sailboat in the midst of an ocean without a rudder, moving aimlessly. He’s always easily discouraged and [disillusioned]. Thank goodness, I found you . . .

ART

I sometimes wonder if my engagement with abstract art is simply escape. When I incorporate fragments of documents and materials from my life into the art, as if to say, “here is some context if you’re lost,” am I expressing reality, or am I eluding more direct communication, hiding from some truth? Maybe I think and see like this because of the gaps and silences I’ve lived with relating to my parents. Maybe it’s just the reality of modernity: fragmentation.

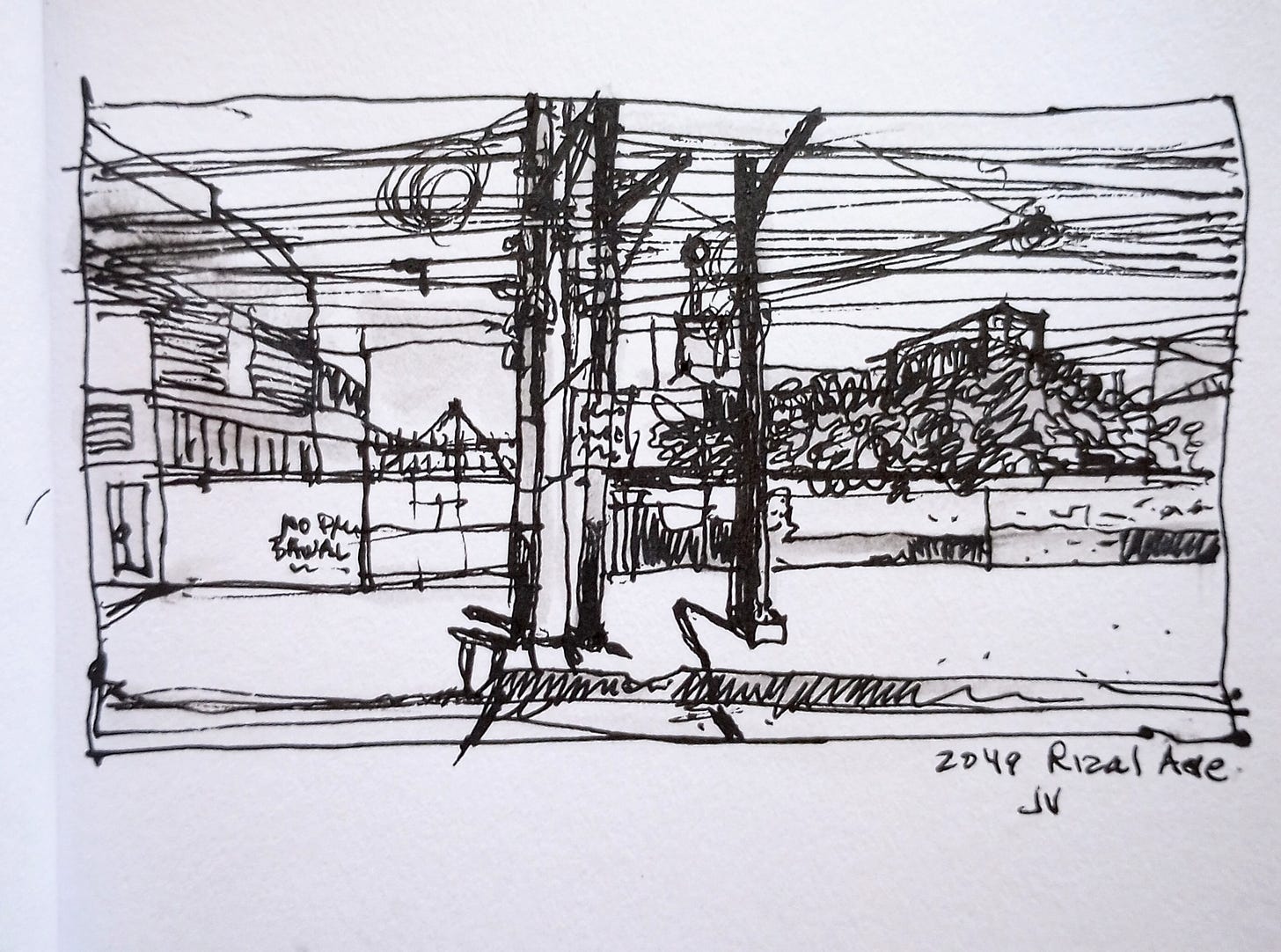

Sometimes, the simple act of sketching seems more truthful—where the artist’s hand, the individual nervous system, is expressed in line and colors. Below, a quick and rough sketch of 2049 Rizal Avenue, from Google Maps, May 2024. The beauty parlor is gone; all that’s left is what seems to be a vacant lot behind a wall, a tree, and the ever-present telephone poles and electric lines overhead.

Beyond style and form, my mind also mulls over questions of privacy: Why bridge the gaps of abstraction? Why not keep things private? Perhaps my parents had good reasons for keeping mum about their lives.

On the other hand, as a writer, I shape the narrative. There’s that side of me that enjoys “detective work,” researching, exploring, stepping into dark places and turning on the light. Part of me enjoys the act of writing, communicating, and (as an artist) drawing the line that might become a letter, a word, an urban sketch, a house, an avenue in Manila. And some parts of the story I will keep to myself.

RABBIT HOLE

Richard Steven Street photographs working people, border crossers, and in this case, Hmong artists and storytellers.

Singaporean artist DrewScape (Andrew Tan) gives you a “contour drawing” crash course—incredibly helpful for urban sketchers and artists who simply want to loosen up while drawing from life:

Articles by Jurgen Kremer, Leny Strobel, Lily Mendoza, James Perkinson, Leta Kingfisher and others in “Ethnoautobiography: Creating Decolonial Islands” (ReVision, Spr 2023):

I’m reading Hernan Diaz’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Trust, and his ideas about power, writing, and rhetoric are reverberating as I think about the letters I’m writing about, what they tell me, and what I choose to communicate. Check out this Paris Review interview with him, “Writing is a Monstrous Act: A Conversation with Hernan Diaz.”

As an editor, I have worked with Mongolian art historian and writer Uranchimeg (Orna) Tsultemin, PhD, and her work opened my eyes to the wonders of innovative Mongolian contemporary art, and also to the rich history of its arts culture and the difficult social and political conditions Mongolian artists have endured. For example, I learned about Mugi (Munkhsetseg Jalkhaajav), whose special area of interest is the female body and notions of “pain, fear, healing, and rebirth”:

Local Arts & Culture:

Pacific Grove Art Center’s new exhibits. The upcoming show, Sept. 6 - October 24, includes artists Zoya Scholis, Jan Seigler, Jill Casty, Saschja Marseguerra, Kristy Chettle, John Dotson, and Elizabeth Wrightman. The exhibit opening will take place on Friday, September 6, 2024, from 7-9 pm. I hope you’ll attend!

SOUNDINGS

Transformations

André 3000 was (perhaps still is) considered to be one of the top ten rappers in the world. He achieved fame and fortune. But one day he retreated from public life and taught himself to play the flute and other woodwind instruments. He began pulling from influences like John Coltrane, Steve Reich, and Phillip Glass. He created “Listening to the Sun,” part of an album he called New Blue Sun. Note: the album video below is about 85 min. long. Definitely not rap—but something else you may have to define for yourself. Andre 3000’s story in GQ.

On Sept. 3, 4, and 5 he will be performing at the Henry Miller Library in Big Sur. Note: don’t try to drive there (because of the slide)! Check instructions for taking the shuttle.

Over the years, Steve Martin has gone from being a great comedian to being a damn good musician and banjo player. Here he is performing with the Steep Canyon Rangers for Tiny Desk Concert (NPR):

A big thanks to all of you who read Eulipion Outpost regularly, and to those who have subscribed here or donated on my Ko-fi page to support my efforts.

My ongoing appreciation goes to the Mysterious M. for his editing.

My website (under construction) and blog: Jeanvengua1.wordpress.com

My Links List is on an old-school Neocities site that I built.

Eulipion Outpost is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

She had been generally unwell right after the War. A situation that later temporarily prevented her from boarding the ship that would transport her to the U.S.

Coincidentally, my parents’ first home in the U.S. was in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

Basically, the ability to create using what you’ve got, and somehow survive.

According to Spot.ph, Dulumbayan comes from “dulo ng bayan,” or “the end of civilized territory as the Spanish saw it then.”

Can’t help but think of the oculist’s sign in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby—the god of capitalism is watching you!

Wow, Their letters are riveting...does your heart beat each time you open an envelope and unfold the letter? Keep going. Acid free sleeves. Bahala na!

I am imagining your mother’s beauty shop, the exterior based on your findings from the period and the interior with the items from your dad’s PO.

Thanks for sharing your parents’ correspondence.