Entering the Portal

#129: Arundhati Roy, Patrice Vecchione, Nico Chilla, Rachel Kwon, Mike Krahulik, Keith Haring, Helen Redfern, Sinead O'Connor & Willie Nelson, Chino Alfonso & Cyril Sumagaysay

HERE & NOW

As the year 2024 commences, I’m thinking of dragons. According to the lunar new year zodiac, this is the year of the Wood Dragon. In a positive sense, it represents creativity, courage, energy, and innovation. Less positive attributes include pride and a tendency to be domineering and impulsive. I think we’ll need those positive aspects during this election year, since—building upon all the chaos of the last decade—it’s promising to be one helluva dragon-lit bonfire.

I’m also thinking of the Philippine water dragon, the Naga, also known as the moon-eating Bakunawa—of which there are a number of myths originating from various parts of the archipelago. According to the myths, the people would go outside during an eclipse and beat on drums, pots, gongs, and kulintangs to keep the greedy dragon from swallowing the last remaining moon of the seven that had been in the sky. The racket they raised caused the dragon to retreat.

At least two of four lunar and solar eclipses will be seen across large swaths of North America this year. Perhaps we should have a party and beat those gongs—make a noise and celebrate our resistance and potential for positive change.

When we all found ourselves in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, author Arundhati Roy wrote about the pandemic as a huge rupture within the dominating systems that have bound us, suggesting that we view the global event as a portal:

“But the rupture exists. And in the midst of this terrible despair, it offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves. Nothing could be worse than a return to normality. Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next.

We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.” —Arundhati Roy

ART/WRITING

Patrice Vecchione answers Six Questions:

I met Patrice Vecchione years ago when I lived in Santa Cruz. She was part of a women’s writing group that had various incarnations. The group included the poet Bernice Rendrick, mentioned in #124. Our discussions and critiques taught me a lot and provided support during my early writing days, which, for me, were fraught with self-consciousness and earnest experimentalism.

We both live in Monterey County, where Patrice continues to write and teach, responding to life’s ups and downs through writing, art, walking, and living her truth. I’m happy to present her answers here; but first, an excerpt from her personal essay, “Meatloaf,” which appears in the Winter issue of Catamaran Literary Reader 2024:

MEATLOAF (excerpt)

Here is the opening to “Meatloaf,” Patrice’s personal essay that appears in the Winter issue of Catamaran Literary Reader 2024:

If my family’s troubles began at a particular moment in time and could be attributed to a singular act—because isn’t there always a precise starting point for everything that goes wrong—perhaps the demise of our family was set in motion with the meatloaf, with the last twist of the peppermill and the final dash of salt before it was slipped into the oven. Though, admittedly, it is difficult to lay the blame of such a long, drawn-out dismantling upon something as seemingly inert as ground beef.

My father, being alone with me at suppertime for the first time in my four years of life, had been charged by my mother with feeding the two of us. Had she called out instructions before he dropped her off and said goodbye or had she left a handwritten recipe card in her minute scrawl that only she could decipher on the kitchen counter? Never one to follow directions, and prone to getting lost when attempting to do so, I’m sure my father took the making of the meatloaf into his own hands. “Who needs a recipe?” is, I’ll bet, what he concluded.

Even while in the army, having been drafted during WWII, sent to Amarillo, Texas, assigned to train to become an airplane mechanic, and having absolutely no mechanical aptitude whatsoever, my father took the army into his own hands too, successfully transitioning from mechanic-in-training to draftsman, not that he knew much about drafting either. But he was artistic and highly skilled at exaggeration, able to effortlessly adjust the truth to meet his needs. Throughout his entire 93 years of life, he spoke like an expert on any topic, whether he knew a thing about it or not. So, in his resourcefulness, my budding-draftsman father got himself an unusual job for any army private and spent the entire period of his enlistment working as a forger, providing officers with leave passes that they weren’t entitled to. But that’s another story, and, anyway, what’s forgery compared to being charged with feeding his little girl? . . .

1. Where did you grow up and how did that (or any other significant experience you’d rather address), influence your art?

My first eight years were spent in New York City—first Queens, then Washington Heights in upper Manhattan. Other than a few childhood relationships—with my parents, the woman who took care of me while they were at work, and my nearby Italian American family—there was no greater influence on my art than New York, along with the loss of it when we moved away, which probably only strengthened its hold on me. The city, and the way we lived in it, provided my insatiable curiosity with such joy, and the relief of knowing I’d never be sated because there was always more there to be captivated and claimed by. My mother wanted me to be, as she used to put it, “a cultured child,” and by cultured, she meant the arts. She was bent on exposing me to them. We frequented the Met, the Museum of Modern Art, saw the Pieta when it came to town and the Mona Lisa; went to the ballet a couple times a year, and watched Leonard Bernstein conduct his Concerts for Young People. Our apartment was near the Cloisters, and my mother often took me to see the unicorn tapestries that fascinated me. Ballet classes too, starting when I was 3 or 4. And there were the skaters at Rockefeller Center around Christmastime.

She read me poetry from the time I was born, then picture books. I think, and I’ve never realized this till now (so thank you, Jean, for asking) that the poetry my mother read me influenced how I saw and came to know New York. It showed me that the world, our world was celebration-worthy, for a poem is a kind of celebration. Whether it was “The Swing,” by Robert Louis Stevenson (and I loved to swing) or the poem by Eleanor Farjeon about the tides, it all drew me to pay attention to what was around me, to see it and be in it, at a sensory level, and to celebrate it. I was flooded by it all.

And the city’s food influenced me too, from lunch at Schraffts or Chock-Full-O-Nuts to lemon ices from La Guli’s near my grandparents’ home in Astoria, Queens and the traditional Italian dinners prepared by my grandmother as well as my mother’s fabulous cooking, and then, of course, pizza by the slice—so hot that you had to blow, blow, blow before taking the first bite.

All of that made me want to respond; it lit and fueled my nascent creative nature. I remember a sense of “Oh, the world is THIS big! And I am alive in it! Here’s what I have to say about it!” At first, making art meant coloring with crayons. It was something I did, as many children do, for hours a day. Charles Wright said, “What lasts is what you start with.” This is certainly true for me. Much of my writing is centered in my early life and what came after, how being told things were true that I didn’t think were true—that conflict—propelled my creativity. Being in the city, simply by being out in it, there was truth and clarity, and I was convinced of it, which gave me a way to contrast what at home was sometimes muddled.

2. What’s your creative process like?

My heart-mind is frequently alight with some possibility or other that I might explore and run with; to call it an “idea” would minimize the whole body-heart-mind experience. Sometimes, there are multiple possibilities calling to me. If my daily life is too full, I either don’t notice or can’t spend time with whatever’s burbling or trying to burble up to the surface. “Burble” because there’s often a voice that comes with this sensation. I’m living a slower life these days, and that helps me notice more closely. But on the other side, if I’m not engaged in the world to some degree, meaning teaching, writing my newspaper column, doing volunteer work, being with friends, then I find my creativity weakens. A certain amount of stimulation causes my imagination to prosper. When the state of the world is particularly chaotic and frightening, like right now, I may freeze up for a while. Feeling undone by the world or my personal life can cause my imagination to retreat. Just yesterday, feeling sad and frightened for the people of Gaza and Israel, and worried for the U.S., I went for a longish—4.3 mile—walk in the mostly wide-open spaces of Fort Ord land. There, far from the world’s troubles and my own, I felt creative possibilities calling to me. It literally feels like that or as if something’s pulling me by the collar of my shirt. Yesterday, two projects presented themselves. But I won’t tell you about them because these things need to be kept private for as long as required. What I can say is that one is a visual project and the other is an essay.

The making of visual art, which for me is mostly collage, both paper and fabric, and hand-stitched work, often has a more animated quality than my writing process does, or maybe it’s better described as more jovial, jumpier, brighter. Not always but often. Whereas the writing projects whisper, even when they shout; they’re shouting inwardly rather than outwardly. They feel more circuitous, concave, spiral-like. With both forms, what I end up with is never exactly what I set out to do. The process of creating greatly influences what is created. In a very tiny way, maybe it’s like becoming a parent—a person has a baby who grows up into someone they couldn’t have imagined.

When possibilities come to me, I don’t always—am not always able to—jump into them, but I often jot notes. Not only do the notes themselves help me to remember and further the idea, but by writing something down, I honor and celebrate what’s come to me, and then more comes. It is easy for me to devote myself to writing a book. As one who loves ritual and boundaries, devoting myself to a writing project is easy—the carving out space, making a schedule. But if I’m not working on a book or on a big art project, I tend to be less focused, that’s why I love a project, the parameters it brings!

3. Does age factor into your creative process, and if yes, how?

The sense of seeing, experiencing life for the first time, part and parcel of childhood, is essential for me in order to do my best work. As Picasso said, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist when we grow up.” So I’m always, at least partly, a child when I make visual art. During childhood, many people felt free and had a sense of permission, a lack pressure and expectation when they began being creative, and for me that’s carried over. The quality of play is always foremost when making visual work. Out of that permissiveness I make connections, see in new ways, come up with possibilities I’d not arrive at if I felt constricted.

In a way, it’s kind of funny that I have been able to maintain or, at times, return to, that sensibility because, until a handful of years before he died, my father was extremely critical of me, often cruelly so. That began when I was a young child. According to him, nothing I ever did was good enough or demonstrated my true abilities. When I was in the first grade, he prompted me to enter a school-wide art show and then proceeded to make much of the picture himself and to direct my hand in the parts he let me make. When I won second prize, he was thrilled, but I was embarrassed. Still, somehow, as a kid, despite how much his criticisms injured me and negatively influenced some of my later life choices, I was, at least much of the time, able to put his judgement aside while sitting on the floor with a pad of paper and a box of crayons. There was, and is, a quality about making art that is so strong, so vital and persistent inside me, it trumps anything that tries to hold me back, even myself! After making pictures as a little girl, doing stitch-work and painting murals when in high school, my visual expression went underground until I was in my 30s when a friend prompted me to try collage (I’m forever grateful to Alison W. for this!), and I’ve never stopped.

My experience with writing, however, wasn’t one of freedom of any kind. It was fraught all through school, and I think, had my father not been a man who wanted to make art himself, I wouldn’t have come to writing. I would have devoted myself to visual art. My father, mother, and teachers criticized my writing, so to be able to do it, I had to free myself from that hold and evaluation. And that took time. For years and years, I was oppressed by self-criticism and fears about my abilities to such a degree that it often limited and constricted me. Not now though! And not for a number of years. If I’m not childlike enough when writing, if I’m taking myself too seriously and thinking too much about outcome—what I might do with a completed piece, where it might go—the writing becomes stilted and tight, the opposite of what good writing is made out of. Childhood also exists in my writing because my childhood experiences are often a part of what I’m writing about.

4. How do you feel about selling and/or marketing your art?

It’s too much—overwhelming, time consuming, the opposite of creating, and yet, and yet. It’s life for an artist now much, much more than ever.

5. What gives you the most joy in the process of creating art?

Being surprised, coming up with things I couldn’t have anticipated, making new connections, finding links between seemingly unrelated things—images, ideas, colors, shapes, memories, etc. This is true both in writing and in visual art. But in writing, it wows me the most because the connections were just sitting there inside me, dormant, and I was unaware of them. Often, this is truly life changing.

Too, I love the feeling of completion, of having said what I wanted to, and then for that thing to find a good place in the world. An essay just came out in December in Catamaran that I’m very pleased with.

6. What are you planning, or working on, currently, and what impels or inspires it?

The two projects I alluded to above, my next column for the Monterey Herald, some stitching projects, and a new book, and then the one that I think will come after that. I’m inspired by the natural world and memory, the reading I do, and the art I see as well as interactions with others.

Bio

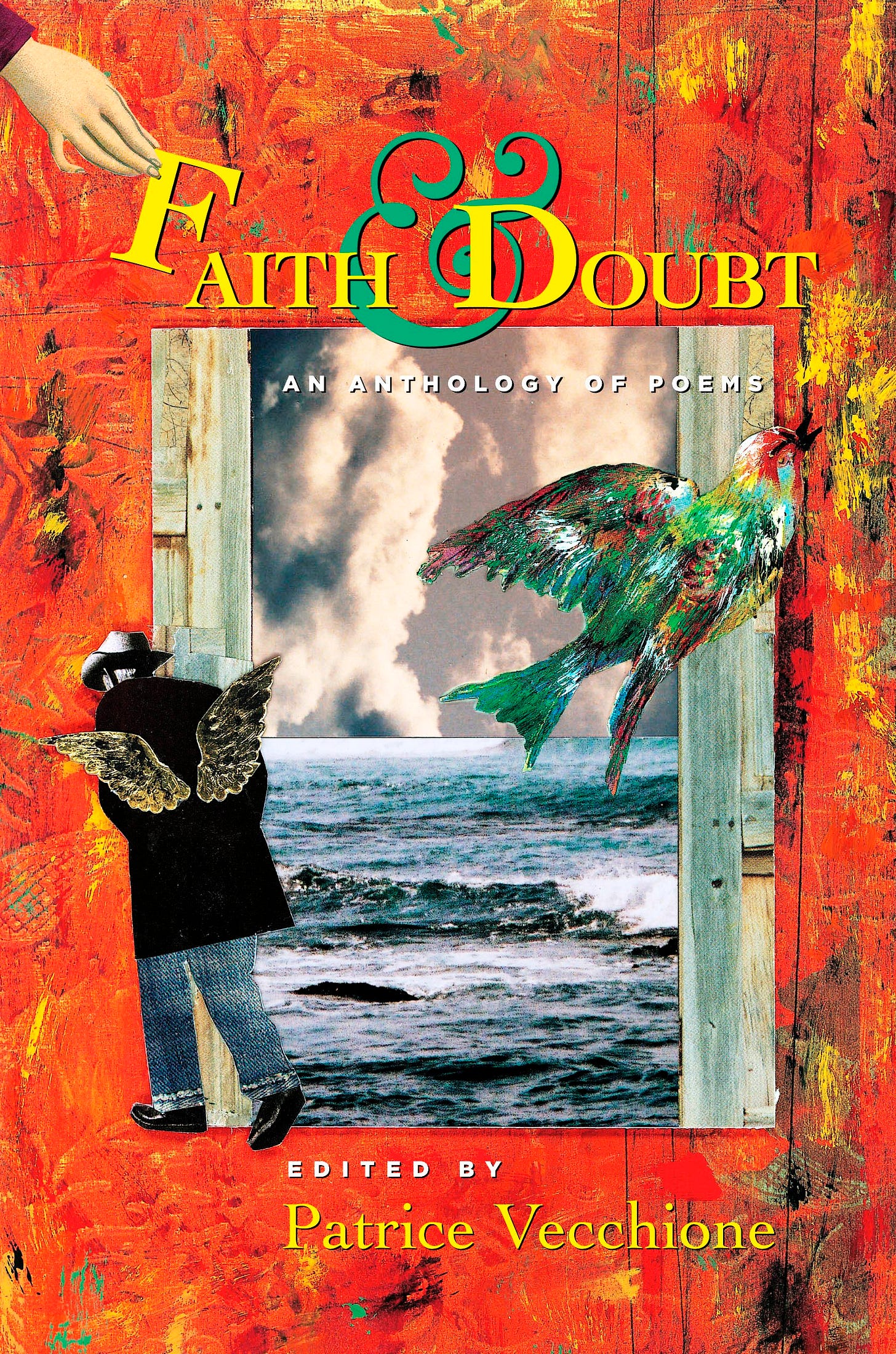

Patrice Vecchione is the author of two collections of poetry, three nonfiction books, and the editor of many anthologies for young people and adults. Her most recent books are the anthology Ink Knows No Borders: Poems of the Immigrant and Refugee Experience (2019) and My Shouting, Shattered, Whispering Voice: A Guide to Writing Poetry & Speaking Your Truth (2020). Through OLLI@CSUMB and elsewhere she teaches poetry and creative writing workshops. Patrice is the Carl Cherry Center for the Arts Poet in Schools, a program that brings her into Monterey County high schools to lead poetry writing workshops. In Fall of 2024 she’ll lead a five-day writing retreat in Santa Fe, New Mexico. More: patricevecchione.com.

RABBIT HOLE

The exploitative framework of most contemporary social media platforms is prompting many to reconsider old-style blogging. See, for example, “My website as home” by Nico Chilla and Rachel Kwon’s blogging links on “The Internet Used to be Fun.” Check out her list of “Things I don’t have to do.”1

Mike Krahulic (aka Gabe of Penny Arcade) has something to say about AI and art, and I totally agree!

“When Capitalist Consumerism Fails an Artist” a video about the artist Keith Haring by Lines in Motion:

“What One Year of Writing on Substack has Taught Me,” Helen Redfern’s commonsense advice for writing a newsletter on Substack. It is detailed, encouraging, and helpful; and it also applies to newsletter writers in general:

SOUNDINGS

I’m thinking of Patrice Vecchione’s blogpost, “Just Keep Moving, Don’t Give Up,” which I found very helpful. Below, Sinead O’Connor and Willie Nelson sing “Don’t Give Up”2 by Peter Gabriel:

Bastille’s Pompeii3 is usually sung at a rousing pace, despite its serious subject. Here’s a slower, contemplative cover, with vocals by Chino Alfonso, and Cyril Sumagaysay on keyboard:

Thanks for reading/listening to Eulipion Outpost. As always, special thanks to my supporters for donations to my Ko-fi!

I have a LinkTree where you can check out my other sites all in one location.

I’m not putting up a paywall. But I will be turning on paid subscriptions early in 2024, for those who wish to support my work through this site. If you haven’t already, please subscribe!

Thx to Jef Poskanzer for the link to Kwon on Mastodon.

Don’t Give Up by songwriter Peter Gabriel. ©BMG Rights Management, O/B/O DistroKid, Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, Warner Chappell Music, Inc

Pompeii songwriter: Daniel Smith. Pompeii lyrics © Wwkd Ltd.