VOICES FROM THE PAST

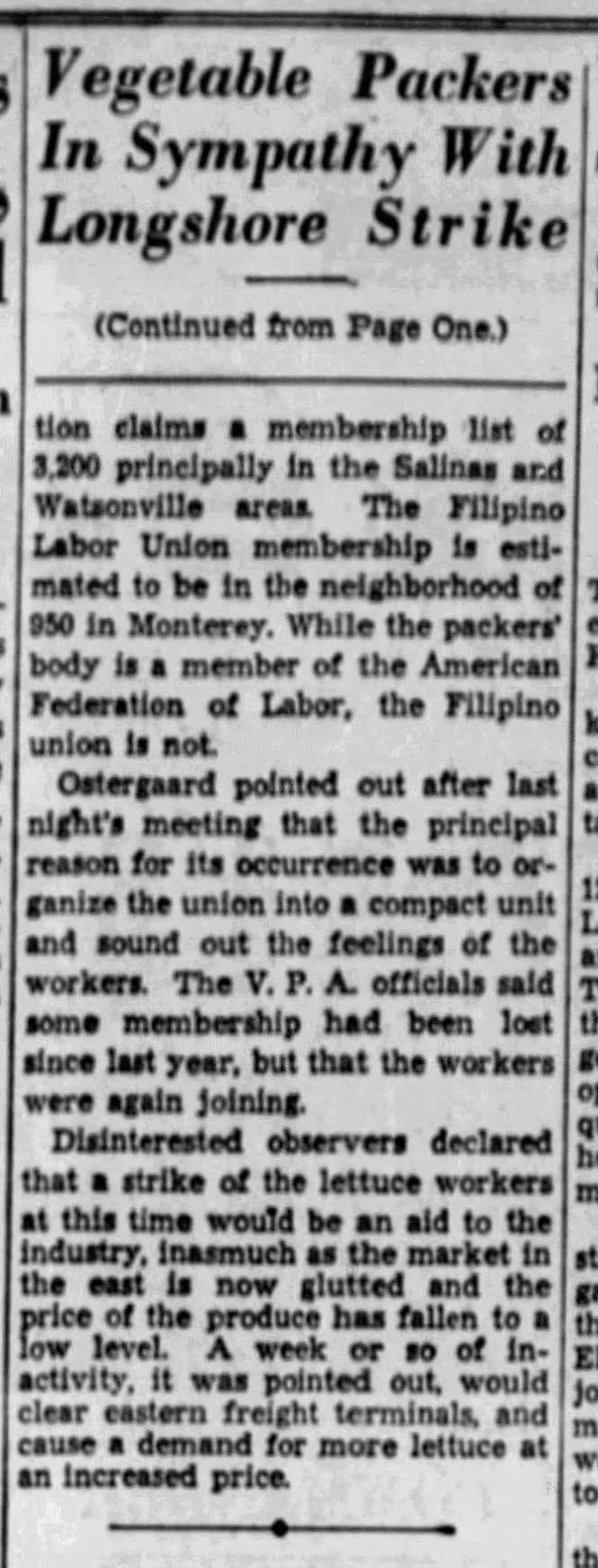

In response to my query about Filipino involvement in the 1934 West Coast Waterfront Strike, historian Alex Fabros kindly sent me the article below. While it certainly suggests Filipino support of the Waterfront Strike in San Francisco, the article does not go into detail as to how this support manifested (as reported by my father)—an event that shut down the City for three days, and came to be called the “Bloody Thursday” strike, which then catalyzed the San Francisco General Strike.1

D.L. Marcuelo and Luis Agudo, mentioned below, were the founding editors of the Philippines Mail newspaper published in Salinas Chinatown:

I can see how Filipino workers may have gotten involved in the Pacific Northwest sector of the Waterfront Strikes, since many of them—like my father—had worked in the Pacific Northwest fish canneries and were members of the Cannery Workers’ and Farm Laborer’s Union. In the 1930s, Filipinos were also looking towards acceptance in the AFL-CIO; showing solidarity with the waterfront workers was also one way to gain entry into the larger union.

However, Filipino workers at that time were deeply involved in their own labor issues in the agricultural fields of central California. I think that the Salinas Lettuce Strikes of 1934 and 1936 were akin to and perhaps emboldened by the larger Waterfront strike and General strike that took place in 1934. Similarly, I suspect that the vigilante response to strikes in the Salinas Valley were inspired by the violent responses of police and hired goons in San Francisco.

From the Commonwealth Club of San Francisco:

I’m interested in the Marine Cooks and Stewards’ Union because my father worked as a marine cook and as a steward on military and merchant marine ships. From FoundSanfrancisco (the San Francisco Digital History Archive):

The militant stand of the MCS against racial discrimination, the practical nature of which was clearly expressed by the union’s high level of racial diversity (40-50 per cent black, 25 per cent Asian, 25 per cent white) is an added distinction to—and in fact is strongly tied to—its commitment to union democracy and its resistance to the tightening bureaucratization and government restraints that followed the wave of wildcat strike activity during World War Two.

Stan Weir, a worker-scholar who spent many years on ships, states bluntly about black and Asian seamen: “they are the cooks, bakers, waiters, and janitors for the rest of us, the lowest paid and the takers of the most crap.” Weir goes on to say that “in ’34, they were some of the hardest fighters we had.”

ARCHIVES

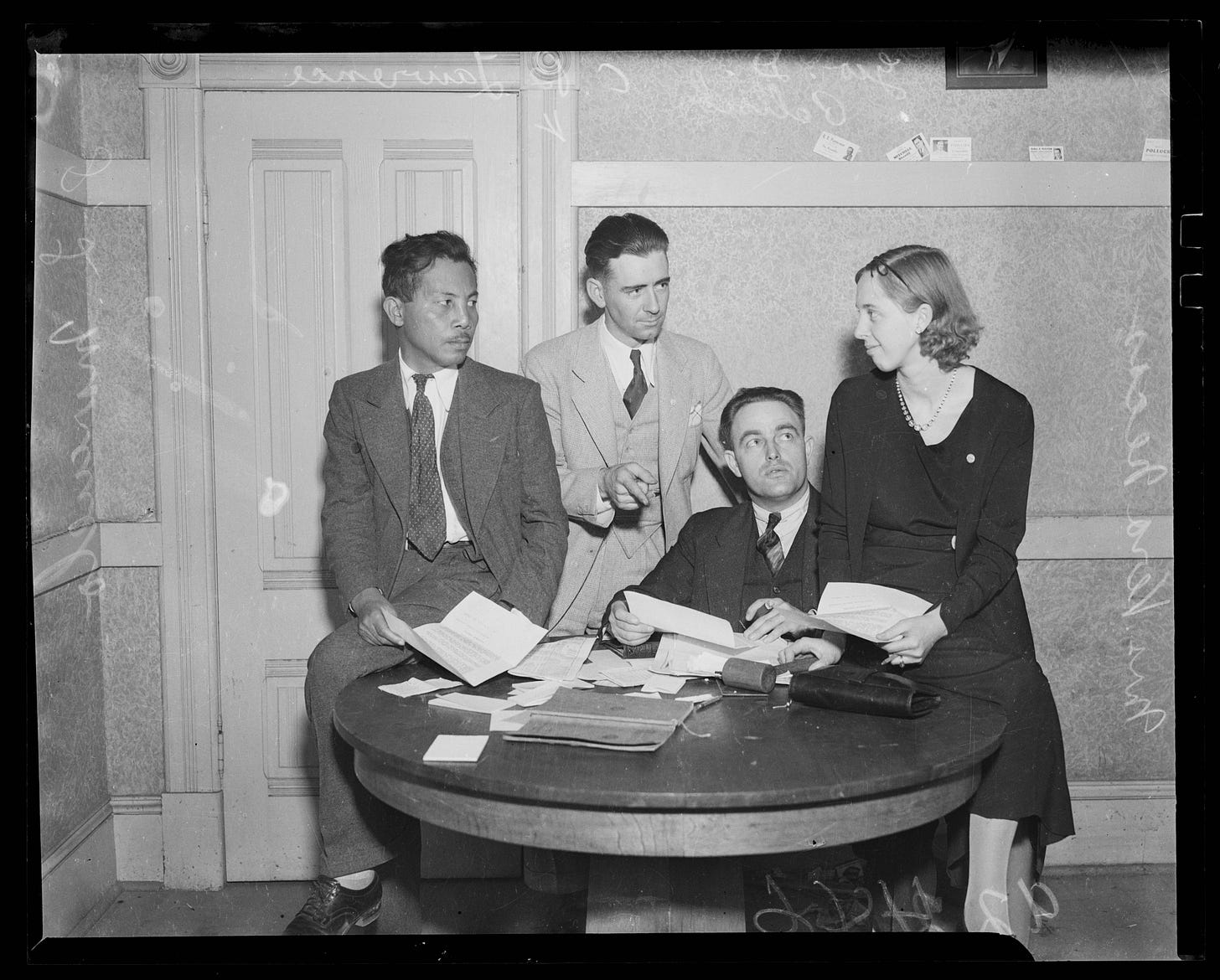

The University of Washington has great resources in their Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium, including photographs and newspaper articles. Some highlights from the website related to the topics mentioned above:

“Filipino Cannery Unionism Across Three Generations: 1930s-1980s”

Newspaper coverage of the 1934 longshoremen’s strike. Note, for example, the Seattle Weekly Voice of Action, which, as early as the 1930s had an anti-racist agenda.

More from archives:

The Public Domain Review is always fun to browse.

The Internet Archive has been having some troubles lately. Don’t forget to browse their site, though; they have some amazing, free archival material, including audio and film media.

CURRENTS

“The National Archives is Nonpartisan but has found itself targeted by the Trump Administration” (AP News)

From the National Security Archive: Disappearing Climate Data (National Security Archive)

Thanks for reading Commonwealth Cafe, and big thanks to folks who have recently recommended it! And do subscribe. it’s still free!

Also known as the “Big Strike.”