Girl’s Guide to Love, Sex, & Betrayal

#123: Then & Now, Joan Baez, Folly Cove Collective, Celia Pym, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Kelsey Rodriguez, Andreas Petrossiants (Mutual Aid), Sarah Cameron Sunde, Mercedes Sosa, and Sama Abdulhadi.

THEN AND . . .

Several days ago I received a stats update on LocalNomad, an old blog I maintained from 2009 to 2012 and had forgotten about. I’d been blogging since 2000, trying out multiple platforms and topics on the internet, finding ways to expend my restless mental energy. LocalNomad arose from my move to Elkhorn (after living mostly in Santa Cruz for decades) and the need to come to terms with the shift from living in suburbia to a rural area that I liked very much, but where I also felt out of place. It was a way to explore my “new” landscape.

Eleven years doesn’t seem so long, but it seems like half a century has passed since then, especially considering what we’ve all been through lately. I’d like to dip back into some of that writing and bring it to Eulipion Outpost, let it play out against current contexts.

The following article was my reflection on a folk music songbook I found in a local bookstore:

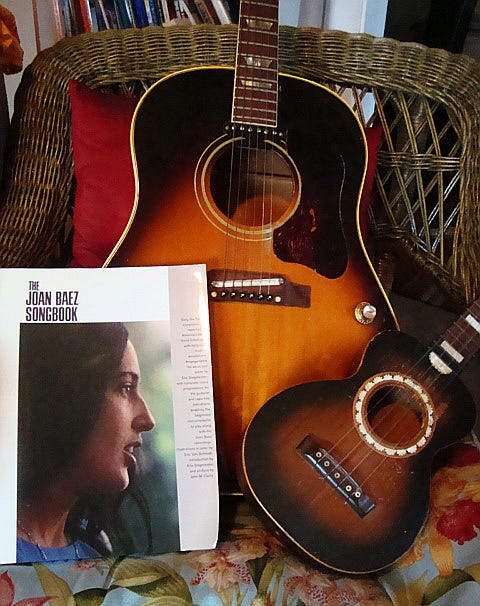

The Joan Baez Songbook: a Girl’s Guide to Love, Sex, & Betrayal

From LocalNomad, 2012.

Recently I found and bought a copy of the old Joan Baez Songbook,1 circa 1964, at Book Haven in Monterey. That brought back memories. In my early teens, I bought the book to teach myself how to play guitar. While I did learn to play guitar (great songs, easy chords), there was much in the book that I could’ve learned from then, but somehow didn’t—and I’m not talking about playing guitar. However, it did give me a preview of adult (and sometimes childhood) life and its travails.

The songbook came out after a long period of dormancy for women who, in the 1960s, after the bland post-war period, were feeling their frustration and beginning to voice it. No perky Doris Day songs here; The Joan Baez Songbook drew from folk lyrics and laments that lay bare the grief and frustration of men, and especially women, throughout the ages.

The intro by John M. Conley reveals how difficult it was in the 60s for women to pull away from a sexualized and romanticized public focus, and to be taken seriously as an artist. In the opening paragraph, he writes:

The paramount fact about Joan Baez is beauty. She has it; she generates it; and she uses it. Lest this seem rhapsodical, be it admitted that she is a human being, with impulses, frailties, and foibles, perhaps even a little young wickedness. But the gospel is beauty.

He goes on like this—focusing on her appearance—for the next three paragraphs, mentioning “the dusk of long hair,” the “deep topaze” (sic) of her eyes, “lithe dancer’s body,” as well as her odd habit of wearing “purposely shapeless” dresses not unlike “gunny sacks” onstage—before finally discussing her musicianship.

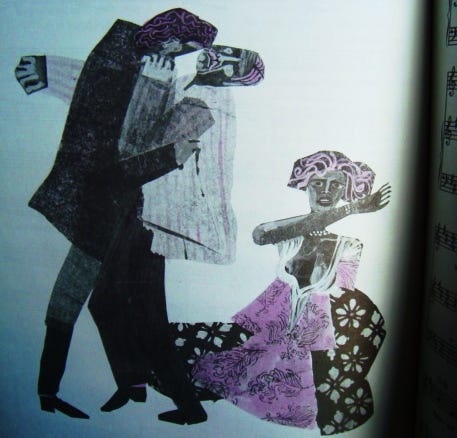

Beauty and love rarely succeed in these (mostly traditional) folk songs. If not betrayal in love, then war, death, or opposition by parents who pulled lovers apart—or sometimes just plain stubbornness. In “The Water is Wide,” the singer laments, “I leaned my back against an oak / Thinking it was a mighty tree / But first it bent and then it broke, / So did my love prove false to me.” I seem to remember that the song, “I Never Will Marry” did at one point influence me to tell a boy that I never wanted to marry (so much for youthful claims)! “I never will marry / I’ll be no man’s wife / I intend to live single / All the days of my life.”

The “Child Ballads” were not very happy either. “Ah, my Geordie will be hanged in a golden chain” (“Geordie”) points to the death by hanging of a young poacher. In another song, young “Matty Groves” beds a nobleman’s wife, and gets stabbed to death by the husband.

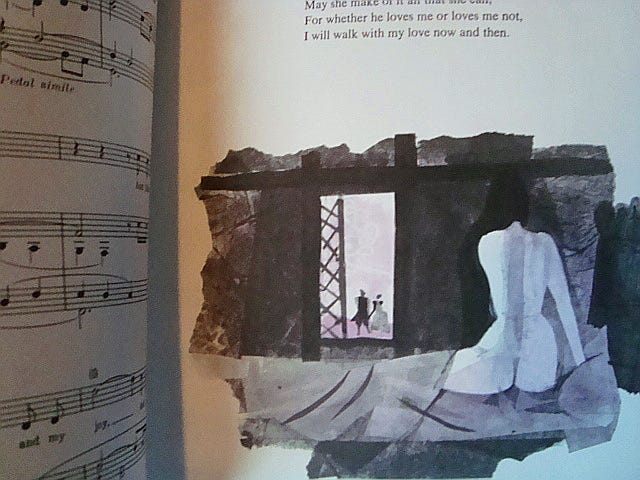

Eric Von Schmidt’s collage illustrations instructed me about the attractions and the dangers of eros; a number of images expressively rendered women nude, or half-nude, or with bosoms nearly bursting from bodices. In all cases, the pictures accompanied songs in which violence, betrayal or loss was the theme. In “The Lily of the West,” Flora is down on her knees, breasts heaving, hysterical as two men go at each other with knives.

In at least two songs, women2 were dressed as men: in “Jackaroe” a woman accompanies her man as he goes to war (of course, he is killed), and in “Ranger’s Command” by Woody Guthrie, she joins a gunfight against cattle rustlers.

The folk laments and high drama of the Songbook were a nice respite from all the ad nauseum “Goin’ to a Chapel and I’m Gonna Get Married” songs of the 1950s and—her amazing voice aside—Joan Baez’s presence in the 1960s was a breath of fresh air for women. A photograph of her on page 9 said it all to me. No cinched waist, no girdle, and likely no makeup. She is facing away from the camera, walking off barefoot through a field wearing one of her “gunny sack” dresses, with her guitar slung over her shoulder. It was a good moment.

Babe, I got to ramble,

You know I got to ramble,

My feet start goin’ down and I got to follow,

They just start goin’ down, and I got to go.

—“Babe I’m Gonna Leave You” by Anne Bredon.

. . . NOW

I’ve spent the last few weeks, and especially the last week, dealing with an eczema flareup on my eyelids. Yup. Ugly, hellishly uncomfortable, isolating, sleep-depriving, unpredictable, etc. Fortunately, a dermatologist and an ophthalmologist came to my rescue. I’d been dealing with low-key eczema for years, and never thought much about it—until it started to get intense and mess with sleep patterns, work, art—pretty much everything. Thanks to the National Eczema Association (NEA), I’ve started to realize this is not just a thing you can medicate and then it’ll disappear. This is all about “maintenance” (more on that term in the section below) and attentive self-care.

As a writer, I wonder if the condition (also known as AD) is some metaphor for stress and “burnout,” for skin as the line between “inner self” and “outer world,” for boundary-setting, even climate change, and all those irksome things that a mind and life can bring up. Perhaps the ancestors have something to say about this. Hopefully I’ll find a path through this process of healing.

RABBIT HOLE

Pioneering print designs from the all-women Folly Cove Collective, circa 1940s-60s. Article by Jenny Brewer in It’s Nice That.

The “Damage Repair Detective” has a new book out: On Mending: Stories of Damage and Repair by Celia Pym. This topic continues to fascinate me. Perhaps it’s just a trend that will vanish, like macrame planters,3 when we all get tired of darning and mending. On the other hand, perhaps this craft will become more artful as time passes, like the traditional and respected art of sashiko in Japan. The topic also prompts me to consider changing and painting over “failed” or damaged art as a “mending” process, not that different from sewing or any other craft. Where does craft end and art begin?

Mierle Laderman Ukeles on maintenance art. What’s the “maintenance” aspect of your art? Is it the chore of cleaning up before, during, and after? Or is your art itself the “maintenance work”? Does it keep the loose ends and dust balls of your life from overwhelming you?

I know this topic is not for everyone—especially those for whom the word and idea of “marketing” is distasteful, tiring, or who hope to escape the hustle by letting a museum or high-end gallery owner sweat it out so the artist can focus, like a monk (ideally with assistants), on their art in the studio. But if you are an artist or writer who has to get in the “dirt” and roll around in it, Kelsey Rodriguez provides a good, practical overview on how to do it without social media:

An alternative to purely capitalist solutions might be in “bridging the work of caring for one another with the work of building our own infrastructures” (Petrossiants), i.e., mutual aid. Well you still have to get in the dirt, but I’m not referring to charity, temporary “crisis aid,” nor “disaster communism.” Rather, it involves actions and projects, small or large, that are potentially sustainable in the long term and can aid and strengthen groups or communities during these extended hard times. Mutual aid is a big topic that I’m just beginning to learn about, so I won’t say much more. Here’s an article on “The Art of Mutual Aid” by Andreas Petrossiants.

Conceptual and performance artist Sarah Cameron Sunde asks what water is trying to tell us about the future:

That was just a taste. But to have a better understanding of the impact of her work, I suggest watching this video (see the link) of her in Salvador, Brazil with people in the community.

SOUNDINGS

In a live 1978 concert Joan Baez sings “Diamonds and Rust,”4 a song she wrote and composed about her relationship with singer/songwriter Bob Dylan. I guess she had some lessons of her own to learn:

Baez goes back to her Hispanic roots with Mercedes Sosa, “Gracias a La Vida”5 :

Going from folk songs to techno raves may feel like whiplash, but I want to end with a celebration of life, sensuality, movement, and survival. “DJ Sama’ Abdulhadi on techno and tenacity: ‘As a Palestinian you know life could be over in 10 minutes’” (Dhruva Balram, UK Guardian). Abdulhadi will be performing in Phoenix in December 2023 and in Dallas-Fort Worth in January 2024. She brings an intense energy to her sets. In the video below, Abdulhadi rolls it out at the Boiler Room, Palestine, with family and friends dancing like their lives depend on it before everything goes to hell:

Thanks for reading/listening to Eulipion Outpost. As always, special thanks to my supporters for donations to my Ko-fi!

I have a LinkTree now, so you can check out my other sites all in one location.

If you haven’t already, please subscribe:

Ryerson Music Publishers (January 1, 1964).

Back then, we didn’t consider whether they were cis-gender or not.

OK, not entirely. The macrame craft seems to enjoying a resurgence.

Songwriter: Joan Baez. “Diamonds and Rust” lyrics © Downtown Music Publishing.

Songwriters: Violeta Parra Sandoval. “Gracias a la Vida” lyrics © Warner Chappell Music Argentina.

I wonder what Joan Baez would’ve been like if she was active now, post-punk & post-feminist, instead of back when every pop music institution was misogynistic to the bone. Not my generation, but it sounded exhausting.

I love that songbook!