In the Land of the Sunrise

#151: Intersections, a Sunrise, Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner & Aka Niviâna, Jerome Rothenberg/Art Ranger, Dyani White Hawk, Sanford Biggers, LKC Band, Imad Fares, Rabbia/Aarset/Petrella.

THEN & NOW

It’s funny how marking a point in time—like one hundred fifty issues of Eulipion Outpost—can change your perspective. After posting the previous issue, I realized the newsletter had been shifting its focus ever since I began writing about my parents and family roots.

I have never been a single-focus kind of person. When I was in grad school, and the concept of “intersecting” genres was taught in my cultural studies courses, it felt “right” to me—it seemed more in line with how I operate.

This is why I’ve changed the summary of this site to begin with “Focusing on intersections of history, culture, and the arts,” and edited the intro in my “About“ page to align with that. Although my art is mostly abstract, my processes always seem to be ghosted by some memory or feeling about history, culture, colonialism, and migration—especially as I read my parents’ letters and research the local and global histories that impacted them and our family.

I continue along those lines in this newsletter, which is becoming a repository of my notes for a possible future book.

IN THE LAND OF THE SUNRISE

In Issue #133, I wrote about Alexandre O. Philippe’s film Lynch/Oz and included a disturbing video clip from “The Return, Part 8” of Twin Peaks.1 Although I wasn’t making an explicit connection, I think, subconsciously, I was tapping into my father’s experience of witnessing a nuclear bomb explode on Enewetak atoll.

This was another one of those events that he didn’t talk about—except to tell me, decades later, that he saw a nuclear explosion on Enewetak from aboard a ship.

I knew that he was working for the US Navy and MSTS (Military Sea Transportation Service) on troop transport ships like the USNS Sgt. Charles E. Mower—previously named the USS Comfort, which he worked on during World War II—and that during the late 1940s through mid-1950s he seemed to be constantly hopping from one ship to another in quick succession. I assume that Dad was part of shipboard personnel staffing a galley, preparing food for military and civilian passengers.

For much of my life, I thought that only one huge bomb had been tested on Enewetak. Boy, was I wrong. My online readings revealed that sixty-seven nuclear devices2 were exploded in the vicinity of the Marshal Islands in 1948, 1951, 1952, 1954, and 1956—all years during which most of my father’s voyages were in the Pacific. But I don’t know exactly which detonation(s) my father witnessed.

My parents kept their tax records from the 1950s, and I saw that Operation Greenhouse was conducted during April-May 1951 (also year of my birth). Dad’s withholding statements for that year showed income from three Navy ships: USNS Aiken Victory, USNS David C. Shanks, and USNS Sgt. Charles E. Mower. The latter, with 178 civilians on board, according to the Operation Greenhouse Report, provided “living accommodations” as a “hotel ship” and “troop transport” during the Marshallese bomb testing years (Operation Greenhouse, pp. 42, 43).

The USNS David C. Shanks was listed as one of the ships at Enewetak in 1952, with 169 civilian personnel. During Operation Ivy Mike (1952), 157 vessels were employed to “transport 2,662 passengers and 143,447 measurement tons of west and eastbound cargo, exclusive of personnel and cargo carried in Navy Task Group ships. A total of 12,235 passengers and 2,225 short tons of freight were airlifted west and eastbound” (Operation Ivy Final Report, pp. 29-30).

Could my father have been one of the crew members “located at random positions when on deck” wearing “film badges . . . used to determine the mean intensities encountered by the crew when topside” (Analysis of Radiation Exposure, p. 14)?

In a letter on US Marine Corps letterhead (February, 1951), Dad wrote that the rocking of the ship from rough weather was forcing him to change positions in order to brace his arm while writing. He describes his work as being “terribly tough and hard,” and that he was “working like a slave.” He complained: “Just imagine feeding about 150 people with limited help and space. The weather has also added more to our miseries. I just wonder how much [longer] would I last. Somehow, I’ve [got] to keep up with my work. Our future depends on it.” Mom was pregnant with me and living in a tiny, noisy Chinatown tenement apartment; he was feeling the stress of his responsibilities to provide for his growing family and hoping that, in the near future, he could move us to a better apartment in Chinatown.

In March, 1951, from the USNS Aiken Victory in San Diego, Dad hinted mysteriously of his destination: “Tomorrow morning we shall be getting underway with full capacity in [sic] load of passengers. No definite destination. All we know is that we’re heading toward the land of the Sunrise.” Dad’s reference might be understood in terms of his security training. In a 1952 report, breaches of security in the form of information leaks to newspapers were discussed regarding “eyewitness accounts derived from letters in the forward area to friends, relatives or families. All personnel, who have been identified, have admitted they were indoctrinated in security Precautions and self-censorship” (Operation Ivy 1952, p. 27).

Below: “Hydrogen bomb exploding in the Pacific Ocean at the Marshall Islands (Castle Bravo 1954)” from The CentralNuclear (video):

In July, 1951, Dad wrote to Mom from the USNS David C. Shanks, which had just arrived in Guam; he noted that they had left Kwajalein (in the Marshall Islands) four days previously.

Knowing about his frequent shipboard transfers, I wondered if he had been on the USNS Sgt. Charles E. Mower several months earlier. On April 7, that vessel had evacuated personnel from Enjebi at Enewetak atoll at 11:00 a.m. It then anchored off Parry Island to await the “H-hour” detonation of what was called, oddly, “DOG.”

GREENHOUSE consisted of four detonations In April and May 1951 on the northeast islands of Enewetak Atoll. Task force personnel were stationed either on the southern islands of Enewetak Atoll, on ships, or at Kwajalein Atoll about 350 mi (650 km) southeast, depending on their mission (Operation Greenhouse 1951, p. 19) .

It’s possible that Dad was also in the Marshall Islands area during another detonation, called “EASY,” on April 17.

No persistent radioactivity was encountered, although [the USNS Sgt. Charles E. Mower was in slight fallout following shot DOG, and the ship was effectively decontaminated by hosing with saltwater spray. Personnel monitoring teams gained limited experience in personnel monitoring, but effective monitoring, decontamination, and disposal of contaminated clothing ashore eliminated all personnel contamination. Showers and sinks installed on the main topside deck were never used. Embarking personnel were monitored for a limited period, but no contamination was discovered (p. 62).

The most powerful weapon ever exploded by the U.S. military was called “Castle Bravo,” and it happened in 1954. My father was still working the Pacific routes at that time, but I don’t know if he was at the Marshall Islands for that one. Was that the image that remained in my father’s memory when he told me what he witnessed?

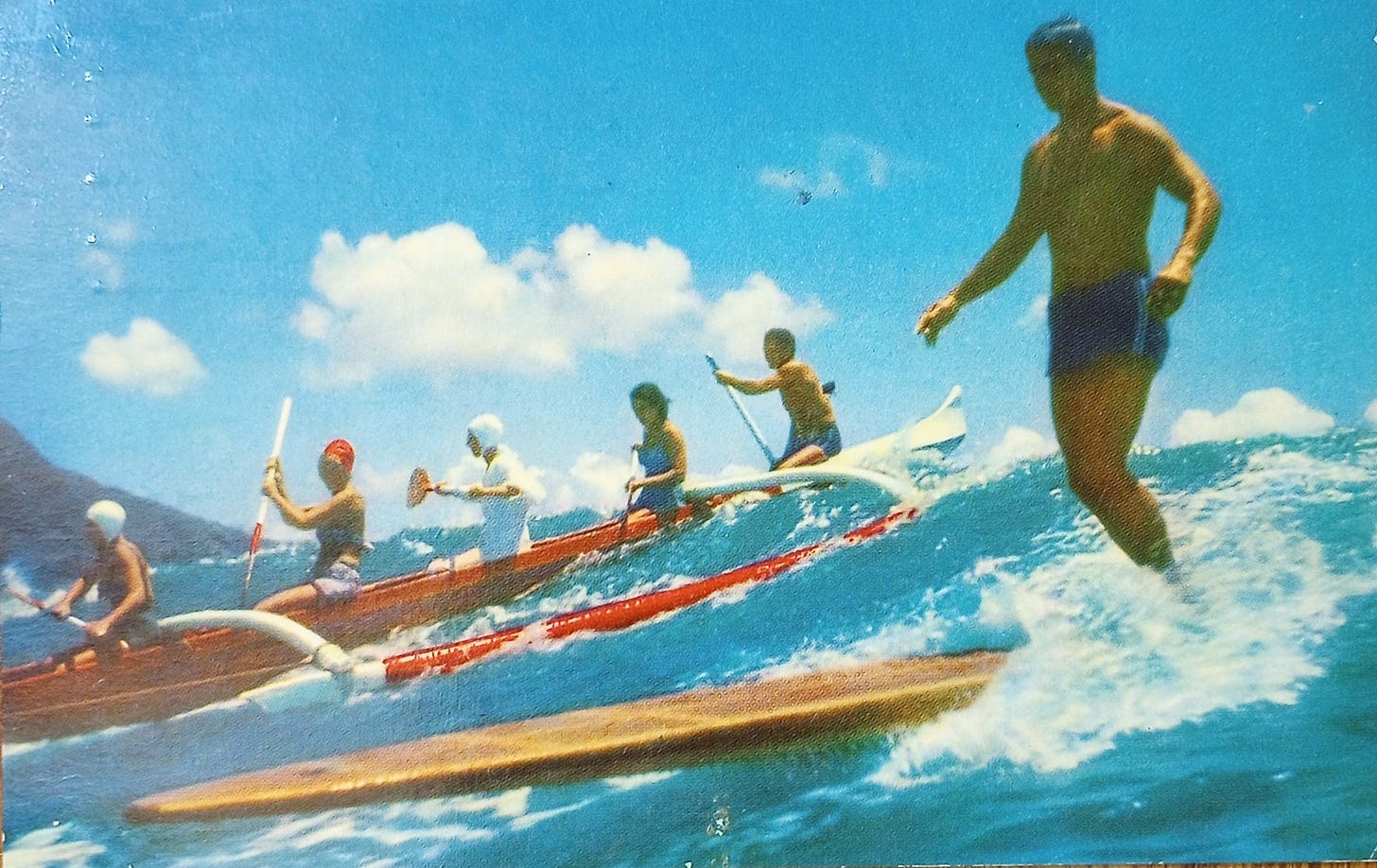

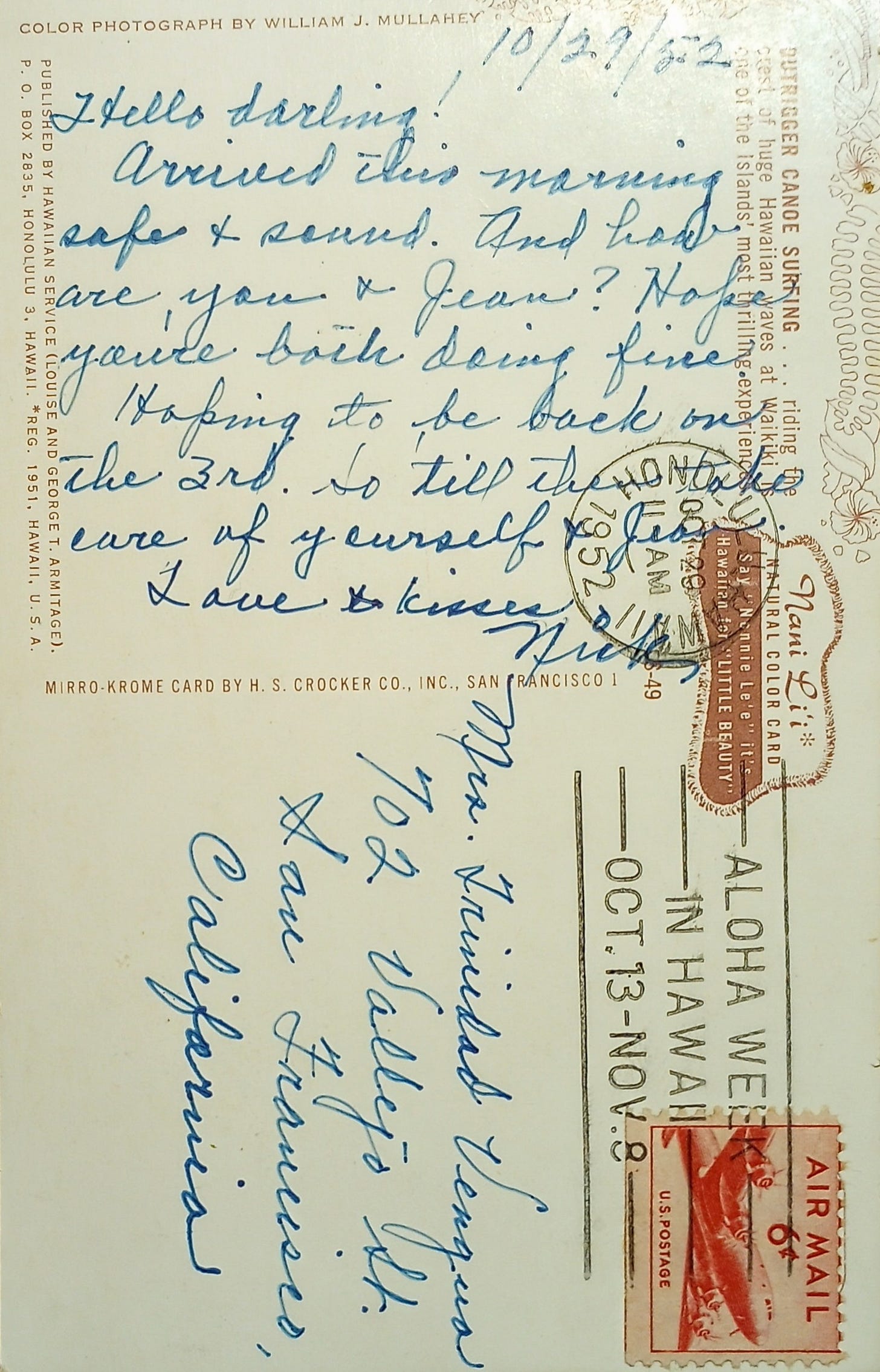

By early summer of 1952, all of Dad’s letters to Mom were addressed from Honolulu; they were all short and unusually upbeat, and he even included a couple of Hawai’i postcards, suggesting he was having a great old time. Was he relieved to be away from the bomb testing? Or was he instructed to keep communications light? I haven’t (yet) found any letters from October or November of that year (another big bomb was detonated in early November), but I did find two postcards, one dated Oct. 29, 1952:

There are still a lot of gaps, and many more letters that I have not yet opened. I will dig into this and other family stories further . . .

Nearly one-third of all the Marshallese in the world now live in the U.S. Many live in Arkansas, in the town of Springdale. The climate crisis is now accelerating their migration. A 2019 article in the L.A. Times by Susanne Rust discusses the betrayal that many Marshallese feel, and the pressing environmental issues they are bringing up in relation to the nuclear testing program in the Marshall Islands.

Poet/producer/educator and Marshall Islander Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner performs “Anointed”:

RABBIT HOLE

Marshalese Islander Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner’s art revolves around rituals to process grief. She and Greenlander artist/actor Aka Niviâna perform “Rise: From One Island to Another.”

R.I.P. poet, translator, and anthologist Jerome Rothenberg, editor of Technicians of the Sacred and more. Relatedly, check out the Department of Homeland Inspiration’s latest (sabbatical) podcast, “A Song About a Dead Person.”

Sičáŋǧu Lakota artist Dyani White Hawk discusses Lakota and Contemporary art in the “mix” of her life experiences. I love her ideas of “storied abstraction” and “bodily recognition”:

Intersections: artist Sanford Biggers:

SOUNDINGS

Marshallese Likrok Kava Club Band performs “Jabro”:

Algerian guitarist Imad Fares performing in Krakow:

Michele Rabbia with Eivind Aarset and Gianluca Petrella performing “Nimbus” from their album Lost River3:

Thanks for reading Eulipion Outpost! Special thanks to readers who have donated here on Substack or in my Ko-fi page to support my efforts!

Website: jeanvengua.com

My Links List is now on an old-school Neocities site that I built.

Eulipion Outpost is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

“The Return, Part 8” of Twin Peaks was written by Mark Frost and David Lynch, directed by Lynch, and stars Kyle MacLachlan.

The Atomic Heritage Foundation calls these “nuclear tests.”

Lost River: ℗ 2019 ECM Records GmbH, under exclusive license to Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Berlin

Holy cow!

You curate the most interesting stuff. I enjoyed Rise and the podcast with Song of a Dead Person. The sound effects were amazing. I have typewriters and appreciated how they were used to punctuate the performance.