Patterns from Ancestors

#149: Davenport Camps, Minimizing, Tiny Naga Book; Substackers, Weijun Wang, Jackson,Alumit, "Utriculi," Ricardo; "Cold Beer," Wu Fei, Grey Filastine, "Music Theory=Witchcraft," and Coltrane.

THEN AND NOW

When I was a kid, we lived in post-war affordable housing in Santa Cruz, CA, across the street from the cannery and next door to the shirt factory where my mother found employment. Every house looked the same. They were the “Little Boxes” in the song by Malvina Reynolds. Everyone in the neighborhood was recovering from World War II, and struggling to survive and raise families in their working class (aspiring to middle class and beyond) neighborhood. They were happy to have these houses. Women were supposed to be homemakers and raise the kids. Men found jobs driving ice trucks, selling vacuums and encyclopedias door-to-door, or building even more post-war housing. The street in front of our house always seemed in a state of being graded (and dusty), or oiled and tarred.

It was a time when fathers quietly, or not-so-quietly, suffered “combat fatigue” before there was such as thing as PTSD. When a visiting salesman discovered that my mom was Filipino, he’d quickly explain, “I was in the Bataan Death March” or “I was one of the soldiers who liberated Manila.”

My mother came from a family in the Philippines that had been heading towards financial security—bolstered by a mining operation my uncles were developing on family land, and a generous aunt who won the Irish Sweepstakes. But the war changed everything. Japanese forces arrived and took over the mine. This reduced the family to a desperate state, moving from one address to another in Manila during the Japanese occupation.

I think this is why mom tended to live always a bit beyond her humble means in the U.S.; the expectation of some cash cow of the future haunted her, and created some financial problems later in life. She had ambitions, many of them projected on me. Nowadays, I think that colonial schooling by Thomasites in the Philippines shaped her perceptions of lifestyle, which contrasted with the realities of a harsher life for Filipinos in the U.S.

As an immigrant who was lonely without her huge extended family in the Islands, it was a big boon for her when when she discovered the Filipino American communities of Central California. And she threw herself into that milieu wholeheartedly. It became another kind of extended family.

The fact that her community involvement took us to nearly every Filipino labor camp in Central California was surely not something she expected to be doing when she arrived here. But in order to support the Filipino organizations that she belonged to, she seemed happy to visit the camps, sit down at their tables for meals, and bring news about the latest lodge or community event and fundraiser, and engage in the latest gossip. She was accompanied by her friends, or my dad (when he was ashore from the merchant marines), and myself.

So I learned that a home life was not always about fancy-looking drapes and furniture purchased from the Sears catalogue. Some Filipinos—especially the men who (like my dad) immigrated to the US during the 1930s to work in the fields—lived hard-scrabble lives with only the most basic furniture.

Despite their stoop work in the agricultural fields surrounding the camps near Davenport (visible today from the Pacific Coast Hwy. 1), the manongs (elder Filipino men) often foraged their food from the sea; they raised their own chickens1 for eggs and meat, and used the “imperfect” vegetables from the agricultural fields (or from the small vegetable patches they were allowed to tend near the bunkhouses) to throw into the stew pot. They served us meals in enamel tinware2 on tables cobbled together from extra wood used to make the bunk houses, and covered with cheap, roll-out floor tiles instead of table cloths.

Those were some good meals, though.

I don’t want to romanticize the camps, however. Except for the amiable old men that lived there, they felt like lonely, abandoned barracks; sometimes you could feel the wind blowing through the cracks in the wood. While some were “livable” bachelor quarters for old men as well as other workers, a few of the camps were truly depressing; we didn’t stay long in those.

Clearly, the owners and labor contractors were not interested in improving their worker housing, other than an occasional fresh coat of paint. As the decades passed, and the manongs living in the Davenport camps aged and died, they were replaced by younger, Mexican fieldworkers. When I was commuting from teaching in Berkeley during the early 2000s, I would occasionally take the long way back to Santa Cruz down the foggy Coast Highway; the bunkhouses were still there, where they always were—and looking about the same as they did in the 1960s—like ghost camps from the Grapes of Wrath.

And here I am, cleaning out all my extraneous stuff3 (see my previous issue for the beginning of that project), saying goodbye to things I’ve hauled around with me for years in boxes. Although I have the photographs to prove it, I’m reminded that I am not the same person I was 50, 30, or 10 years ago. Still, with or without the material possessions, the past has a way of lingering on. My body, brain, and spirit are imprinted with memories, trauma, lessons, and patterns from ancestors, along with my own life experiences, decisions, and their results—in turn producing yet more patterns of thought and behavior.

Am I also clearing out that old American Dream of my mom’s—so closely linked to her ambitions for me and for a life of material wealth, fancy clothes and furniture, not to mention financial security? It’s a question that I still grapple with and probably will until I lose those memories or die.

So who am I now, at this moment? I think—for now, at least—I’m OK with the old zen reply, “Don’t know.” I’m opening up some space in order to hear what wants to speak.

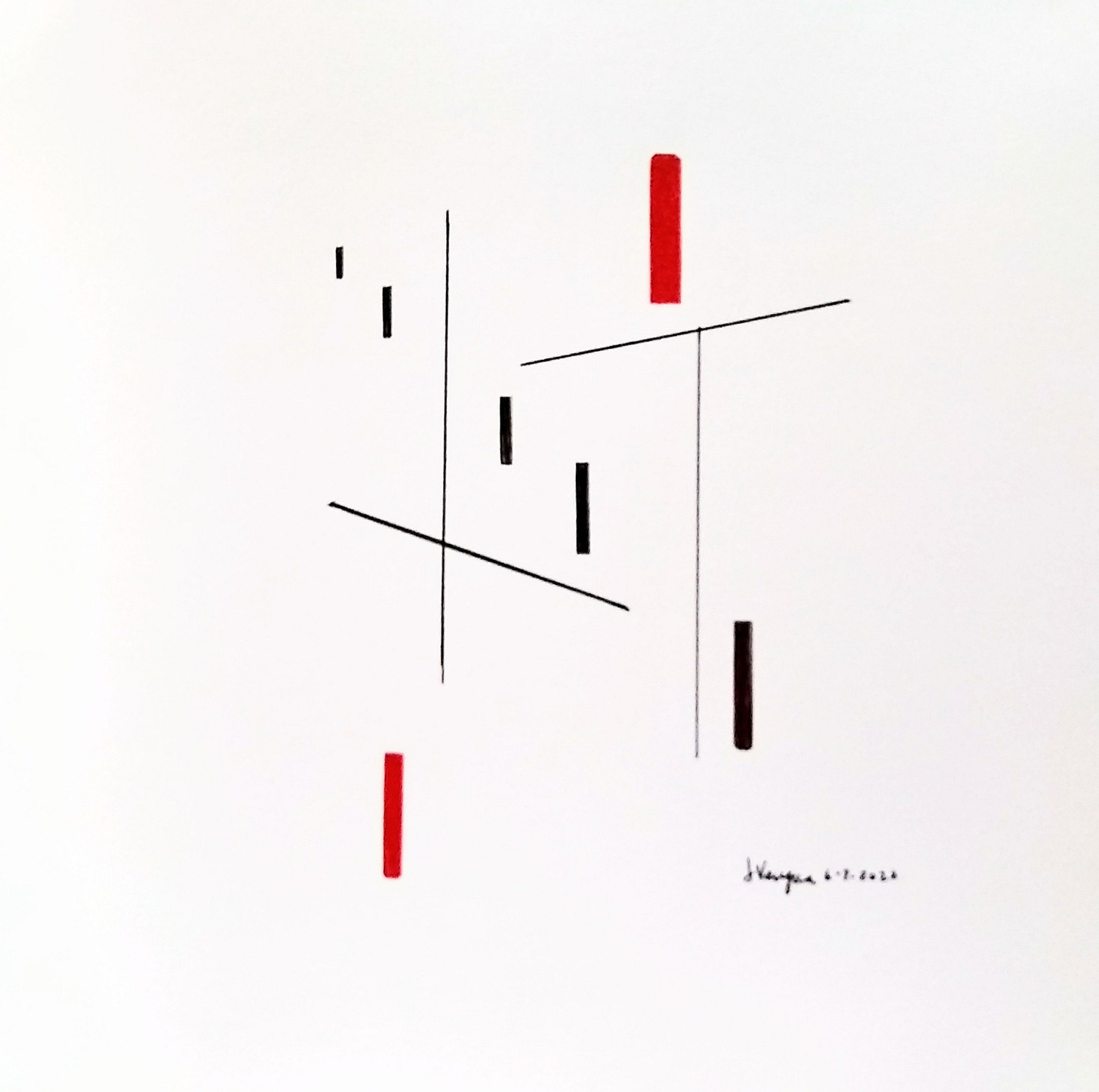

ART

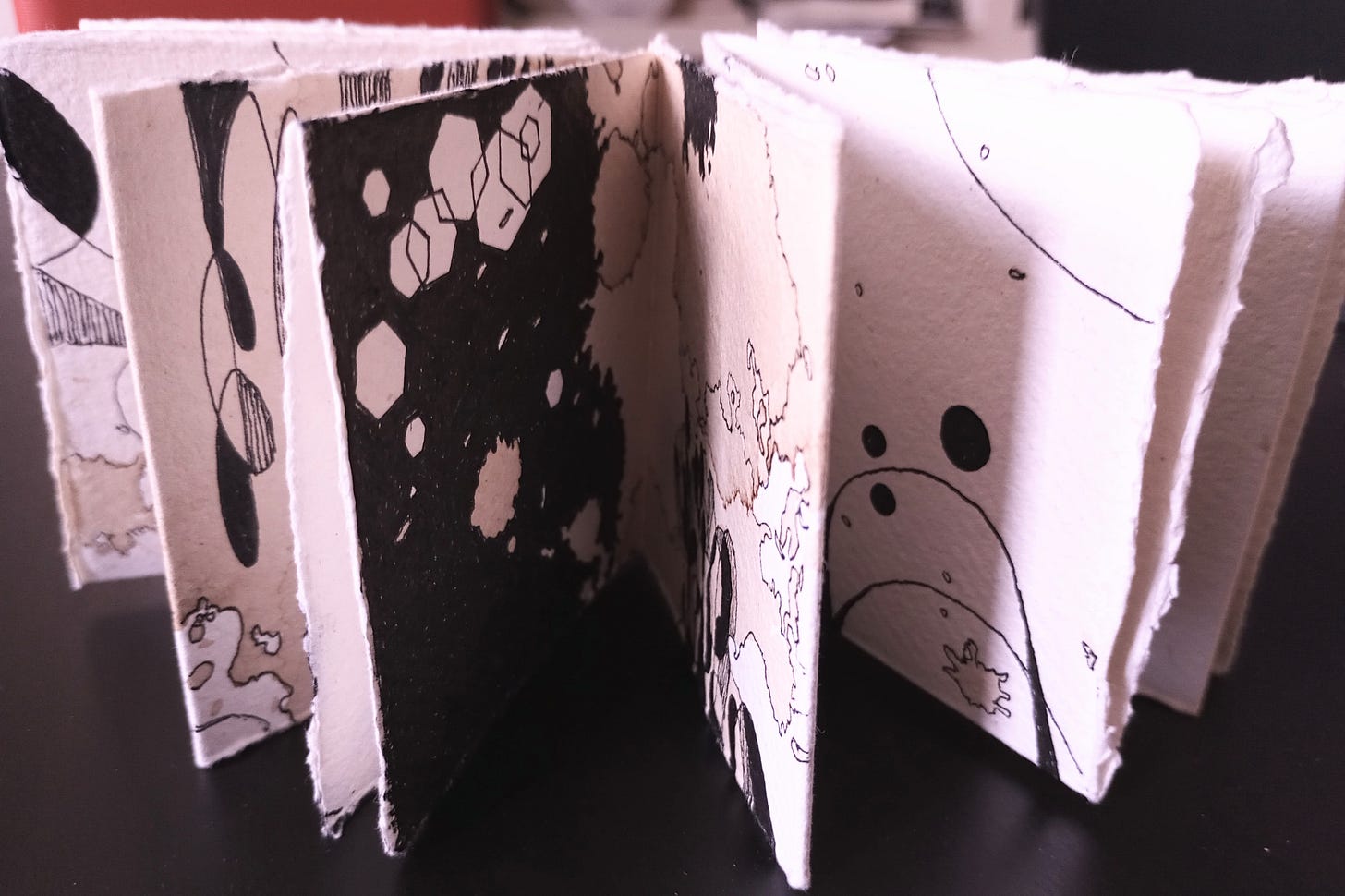

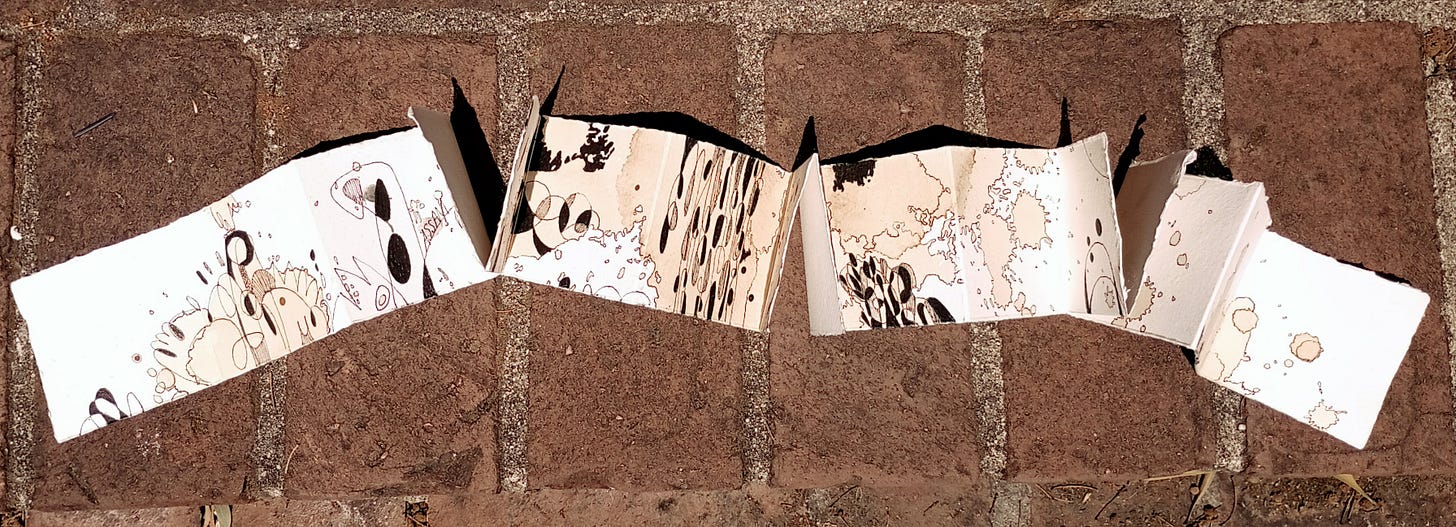

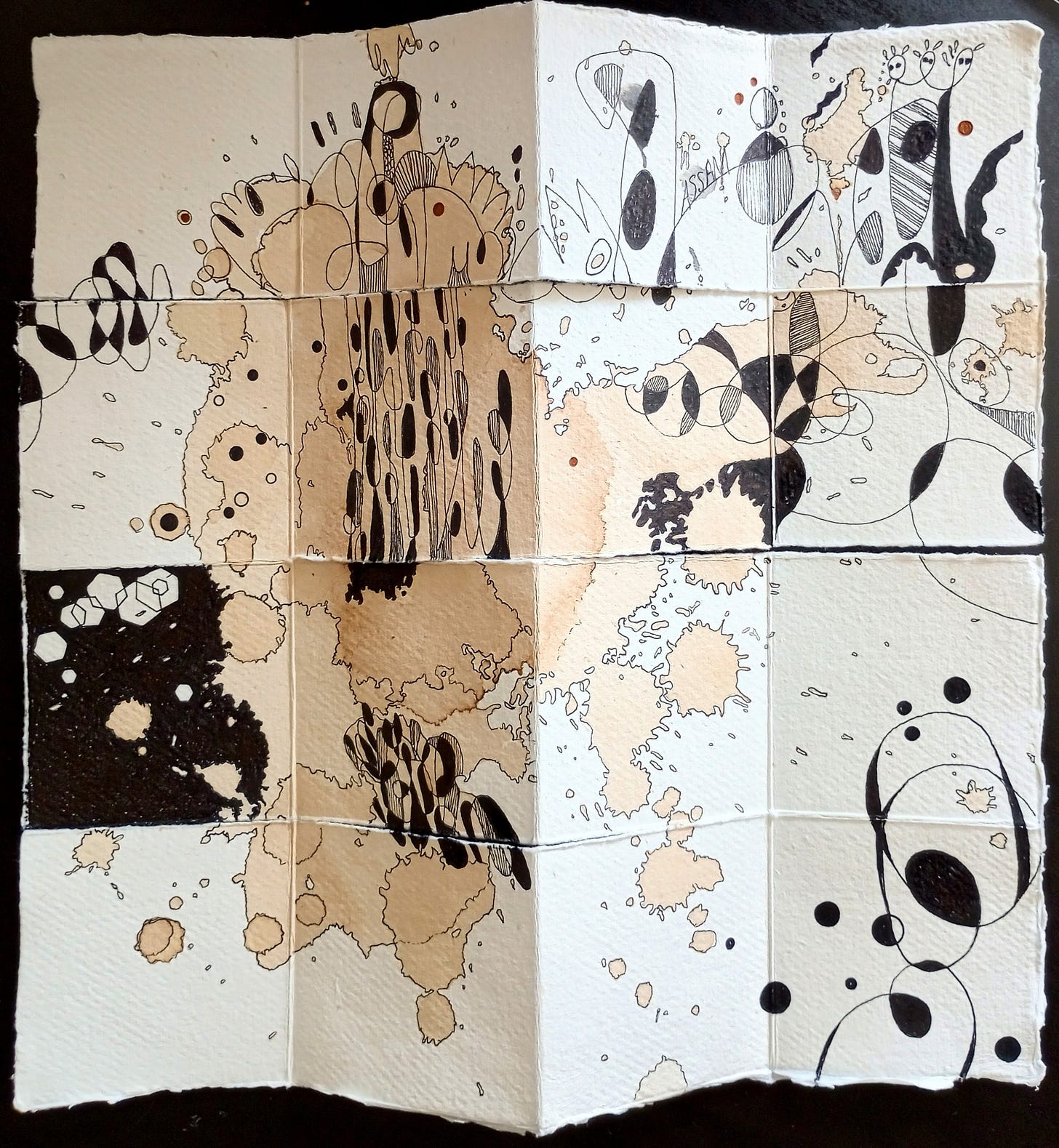

Playing around with the idea of a “naga” (snake fold) tiny book. I splashed tea that I was drinking (sencha and later PG Tips and Dimbula BOP) on the paper for a little color, combined with improvised ink doodles. I’ll make a cover for it. Then maybe I’ll make one with a snake drawing on it.

RABBIT HOLE

Substackers:

From This is Rachel, her latest post “Naked and Stunned at the End of the World” takes a closer look at a tarot card. She also recommended Esme Weijun Wang (see below). I’m thankful for both SmallStack (celebrating newsletters with less than 1000 subscribers w/special love for those w/ 500 or less subscribers) and QStack (LGBTQ+ Substackers).

Esmé Weijun Wang on her book, The Collected Schizophrenias (Greywolf Press), and the realities of her personal experiences with schizo-affective disorder, the academic system, and societal perspectives of mental illness. Check out what she says towards the end about how she deals with her limitations and needs. Her book is definitely going on my reading list.

Local artist Andrew Jackson’s paintings of the Monterey Bay area are haunting; they give us a window into a different side of communities and lives that exist behind the hype of Monterey’s touristy sheen: https://www.outeredgestudio.com/art/ And now his exhibition catalog, Night Works, is available.

In the journal Bodhi Leaves, Noel Alumit writes about Cambodian American artist Pfung Huynh’s project of “Reuniting Buddha’s Head and Body,” which also considers how the Buddha statues became decapitated in the first place.

Utriculi is edited by writer/musician harry k. stammer and poet Mark Young, and they are accepting submissions for the journal’s next issue. Here’s what it’s all about: “Utriculi is currently published yearly with new works of textual poetry, vispo, short fiction, flash fiction, essays, reviews, photographic art, and art. We welcome all forms of experimental literature and art that push boundaries. We welcome submissions from artists and poets of all backgrounds and identities.”

• Mat Ricardo, on choosing the hard but rewarding life of a magician/busker:

SOUNDINGS

I’ve got more sounds than usual for this issue!

A very refreshing track: Cold Beer, by Morosi, Brougher, and stammer.

Composer/vocalist Wu Fei talking about and performing her composition “Hello Gold Mountain”:

Grey Filastine whose music is described by NPR as “powerfully political and distinctly global.” That music is made from found items and found sounds. He and a friend perform “Btalla” from Dance of the Garbagemen:

OK, this is freaky. “Music Theory is Witchcraft” (from the GM Channel).

But also check out John Coltrane’s diagram illustrating the mathematics of music.4 Thanks to the Mysterious M for pointing out this site.

Thanks for reading Eulipion Outpost! Special thanks to readers who have donated here on Substack or in my Ko-fi page to support my efforts!

My Links List is now on an old-school Neocities site that I built.

Eulipion Outpost is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The racist slur referring to Filipinos eating dogs was sometimes used within Filipino circles—especially in the camps, but with a sardonic, in-joke emphasis. Although I’m pretty sure I was never presented with a dog dish, the manongs would sometimes tease kids or each other about what might be in the adobo.

I think these are called “enamelware” plates, often used in camping because they are light to carry.

…though there was a time when each object seemed vitally important and necessary.

Apologies: After posting the issue I realized the link didn’t work; it should work now!