Mining the Silences

#158: Archives, War, and Art; Internet Archive, Caleb Duarte, Paul Soulellis, Artists' Books Cooperative, Newspaper Club, Eileen Tabios, Thom Minnick; Philippine Constabulary Band, and Dan Tepfer

THEN & NOW

Update

After spending some time as an archival committee member for an Asian American nonprofit, the processes we’re developing are teaching me how to preserve my parents’ letters.1

While the scanning process for the letters is still on hold, I decided that I might as well continue putting them in clear, acid-free sheet protectors, and organize them by year in binders. Cardboard boxes do not preserve the letters against things like mold, dust, and dust mites; they’re already undergoing degradation.

Mining the Silences I

This morning, while lying in bed, I found myself grappling with the timeline of my parents’ lives and the events that shaped them. My perspective constantly shifted from the global to the local as I mulled over questions: What prompted my grandfather to join the gendarmerie-style Philippine Constabulary, the military police force created by the U.S. to keep the Filipino nationalists in check during the American occupation of their country? What crops did my grandmother grow on her little farm plot? Living in rural Iba, Zambales, how did she manage to raise four children, on her own, after my grandfather left the family for good and migrated to Kansas, headquarters of the 9th Cavalry?

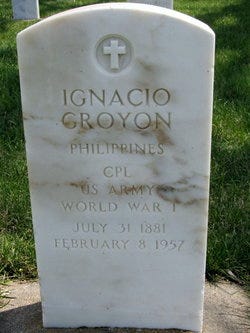

My grandfather’s remains are now interred in the Fort Riley, KS military cemetery. When I traveled to Kansas and saw his tombstone, I was confused by the World War I inscription. “Wait,” I thought, “Did he go to Europe? Did he fight against the Austro-Hungarian forces? Was there another story there that I didn’t know about?” I still don’t know. But I’m guessing that “World War I” is a stand-in for the Philippine-American war.

Grandpa Ignacio was fifteen in 1896, when war broke out between Philippine revolutionaries and Spanish forces. He was eighteen when American forces intervened in the revolution, paid off the Spanish government, and decided to “annex” (colonize) the Philippines—angering the Filipinos who then turned their stymied revolutionary energies against the U.S. in 1899. And Ignacio was twenty years old when the Philippines lost that war, although it continued to be fought, guerrilla-style, for a few more years. The (U.S.) Philippine Constabulary was established in 1901. I imagine that by that time or perhaps a few years later, he had seen plenty of conflict, death, and starvation—and was in dire need of a job and even a sense of belonging, in a country and society deconstructed by war.

My grandfather’s tombstone erases the war—called a “conflict” or “insurgency” by some Americans—that killed “over 4,200 Americans and over 20,000 Filipino combatants. As many as 200,000 Filipino civilians died from violence, famine, and disease” (Dept. of State, Office of the Historian). My mother, the oldest of four siblings, suffered from beriberi as a child, a disease associated with the introduction of white, polished rice, which I assume was imported to the Philippines to ease the country’s disruption of farming and food supplies during the “conflict.”

A summary of the Philippines American War—excerpted from the PBS film Crucible of War:

Once my grandfather had secured his military job, I wonder if he read the Constabulary journal the Khaki and Red, which I found at the Internet Archive. Were he and his wife, my grandmother Matea, intrigued by the articles and the ads for Chesterfield cigarettes and Uncle Sam Polishing Paste for shoes? Did he find some comfort and even pride in the extra income and in his military/police cohort—which later became a musical cohort when he joined the Constabulary Band? Here’s a poem found in the Khaki and Red, which may have helped him to process his position:

Nothing Can Take Its Place2

A fellow buys rubbers to put on his feet,

A hat he obtains for his dome;

And in that direction of needy protection

He bulwarks the place he calls home.

Our fighters in khaki wore helmets of steel.

Our banks have alarms by the ton;

For merely the reason that safety's in season.

A copper must carry a gun.

But think of your Family's future, my friend;

Get wise; use a little restraint,

Despite your endurance, your mite of insurance

Is all that is left when You aint.

— Author Unknown

I have so many questions, many of which will never be answered, definitively. All these people—my parents and other elders—are gone. Yet, as an artist and writer, it’s my job and my passion to speculate and imagine. And there’s always the rabbit hole of research.

ART

First, a brief note: I have a new art website on Wordpress.com.3 It’s very basic, no flash, which suits me fine.

Mining the Silences II

So far, I’ve thought of my letter project simply as an act of writing that requires me to use archival processes in preserving my primary resource: the letters. Lots of writers do research and keep archives as a resource for writing. Par for the course. No big deal.

But I’m remembering archival/art projects by Paul Soulellis, whose work I saw when he was an artist in residence at the Internet Archive, and Stephanie Syjuco, a sculptor whose work involves archival research at the Missouri and Smithsonian archives. I’ve found important information about my grandfather’s Philippine Constabulary band (including audio and photographs) within the Internet Archive and other archival collections. Much of what I’m learning about my parents’ lives is visual, from maps and photographs; even the handwritten letters, address books, and radiograms have a strong visual element.

When art is presented to the public, the struggles, research, and messy or tedious parts are often hidden. Even artists’ process videos posted on YouTube are drastically edited to save time, and also to censor the struggles and mistakes that happen along the way. The process is sometimes accompanied by soothing music.

But can public exposure of my writing and research process in this newsletter be thought of as one aspect of an art project? What do you think? Below, I’ve included links to artists who seem to be doing something like that as well.

I feel like I’m mining silences and gaps for all that was not, or could not, have been said in my immediate family. And those silences have not all come from my parents. There were also my silences, and the times when they were talking, and I was not listening.

Since they’ve been gone, I’ve felt like I’ve been drawing from an endless, black well. But the sounds and visions now rising from it are not just from my parents, in the form of letters, but also from many other voices—from the archives.

RABBIT HOLE

An Internet Archive Artist in Residence, Caleb Duarte’s art is based on research in relation to nomadic and migrating communities in struggle:

For Paul Soulellis, the creator of the Queer Archive Library, publishing books is a social as well as artistic practice. Instead of an art gallery show, “the publication is the show.”4 Below is a talk he gave at the Walker Art Center on how his work on art, publishing, and archives developed. His talk begins with travel to Sicily, where he visited “an archivists nightmare,” a collection of videos from Kim’s Video store chain from NYC, which somehow ended up in Sicily. He and his students found “just piles and piles of stuff.” He considers “how we consume, and save, and savor cultural artifacts, and what we do with our stories across time and space.”

These projects taught me two important things: that “making public” was a powerful way to grow—to give value to my work—and that publishing could be an artistic practice.—Paul Soulellis

Artists’ Books Cooperative (ABC) and a video by one of its contributors, Dawn Kim, called “Loss,” is a reflection on the silences expressed by then President Barack Obama during certain speeches.

Have you ever thought of publishing your own writing and/or art in newsprint? With Newspaper Club, you can make and print your own newspapers, broadsides, or journals!

I’m excited to create more asemic works this year. Eileen Tabios’ The Mortality Asemics, where she used her newly appearing white hairs as asemic art, is one source of inspiration—as it appeared in Queen Mob’s Teahouse in 2015.

What is hair but a line? So I thought to create drawings using hair as a line, or hairs as lines—I envisioned these drawings against dark backgrounds since I would be working with white lines. —Eileen Tabios

I really like the oil paintings of Thom Minnick. His art documents his everyday life and the struggles of the people in it. His videos show his process without trying to hide it beneath a veneer of perfection. I also like the fact that he’s willing to do a completely new version of a painting he finished much earlier.

I am still shying away from working large. Aside from the need for space to make a mess in, the cost of materials, like stretcher bars and other tools, and the work of preparing the substrate (canvas on wood) would be a literal pain for me. As Minnick writes, his experience with preparing a large canvas “was like a war . . . and my hands hurt SO bad. Even after fighting with this thing for, like, three-four days straight . . . "

As for myself, I continue to work small, and with humble paper for my substrate.

SOUNDINGS

The Philippine Constabulary Band plays “La Sampaguita” in 1910:

Salamat to Leny Strobel for pointing me to this beautiful musical sculpture built by French American pianist Dan Tepfer! And here’s an article about it on Aeon.

A big thanks to all of you who read Eulipion Outpost regularly, and to those who have subscribed here or donated on my Ko-fi page to support my efforts.

My ongoing appreciation goes to the Mysterious M. for his editing.

My Links List is on an old-school Neocities site that I built. And here’s my website, currently under construction: Jeanvengua1.wordpress.com

Eulipion Outpost is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Btw, the family of my godfather, Pablo (Paul) Laput, Sr. (who I mentioned in Issue 155, about New Orleans), is going through a similar process, archiving documents and photos and writing about them. They are compiling the information for a book, in part about Filipino men who worked for Standard Oil shipping.

June 1930 edition.

The Notion.so database site did not work out. Long story. Involves money.

He was speaking of Seth Siegelaub’s Xerox Book as an example.

Thanks for sharing the link to Leny Strobel. I listened to her interview about the Babaylans. So true that Filipinos are syncretic by nature.

It sounds like you have a treasure trove of letters from your family. I, too, have tried to piece together my father and his family's past. It's a tough job that I find requires help.

Oh, by the way, thanks for the restack!