"No Bed of Roses"

No. 193: Merchant Marines, Stokely-Van Camp, Urban Sketching? Mutual Aid, Grants & Residencies, Artists & Writers, Susie Ibarra, and Marcus Grimm

THEN & NOW

Boy, did I fall into the research rabbit hole this weekend. Many of the resources I found will go into future issues, or into my research and writing for the book project. Some of it went into what you’ll read below.

It’s Memorial Day weekend, and I’m remembering my dad in the photograph below, in his Steward’s uniform with some of the ship’s staff that he supervised; I think the image was from the late 1950s. While I have quoted his letters detailing how difficult his work was, “working like a slave” in ships’ galleys, he looks quite spiffy here.

I imagine that one of the big challenges of Dad’s work was the fact that he frequently changed ships, switching between US Navy and Merchant Marine vessels during WWII and especially during the decade immediately after the war. The job required a lot of flexibility, being able to work with new staff and management at the turn of a dime, all while dealing with the vicissitudes of weather, war, and transport issues on the high seas.

Merchant Marines risked their lives during WWII and the Korean War, as recounted in “Supplying Victory: The History of the Merchant Marine in World War II” (National WWII Museum).

But what actually is the “Merchant Marine” service? Even I get a little confused about how it differs from other types of marine employment. Maritime historian Anthony DiMattia explains the differences, and notes that during WWII, the Merchant Marine service “was huge; the [US] government built literally thousands of cargo ships to bring supplies to our forces and the forces of our allies…” Furthermore, “Just because you’re on a noncombatant ship doesn’t mean it’s not dangerous . . . minutes before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor they torpedoed a merchant ship called the Cynthia Olson off [the coast of] Hawaii”:

According to Professor DiMattia, very early in WWII (1941-1942), more merchant mariners were dying [from attacks on their ships] on a monthly basis than members of the armed forces. Although he doesn’t speak much about Filipino or other non-white merchant mariners, his talk was an eye-opener for me.1

If you are interested in this topic, a good academic resource about contemporary Filipino seafaring is Kale Bantigue Fajardo’s Filipino Crosscurrents: Oceanographies of Seafaring, Masculinities, and Globalization.

The tasks of organizing and archiving my parents’ letters has been looming over me. Though it’s not my favorite part of this project, it needs to be done, since it will help me place events in the timeline correctly. In the 1940s-50s box, there are many letters without envelopes, and many empty envelopes. I’ll have to sort them by date and match them up. Then I need to scan them and place them in the binder sleeves that I have ready.

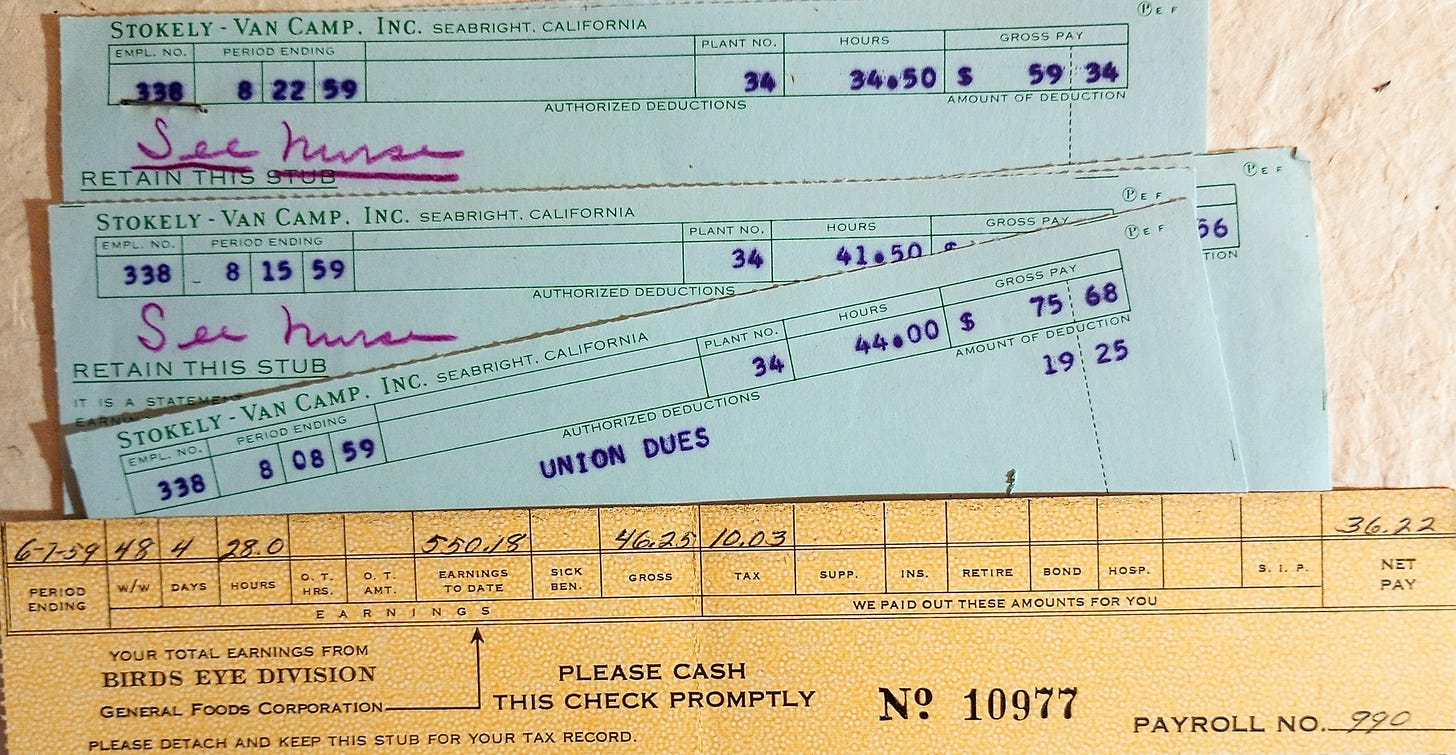

I also have a separate box full of old tax records, employment documents, and documents related to the purchase of the house in Santa Cruz. Many of the papers are folded up and stuffed into manila envelopes. Every time I spend a few minutes unfolding a few of these papers and examining them, I learn something different.

Yesterday, for example, I found a pay stub marked “Stokely-Van Camp, Inc.” (which you might recognize as the producer of Van Camp’s canned pork and beans and Gatorade). I realized that I was unaware, or perhaps had forgotten, that Mom worked for Stokely’s, as it was called locally, as well as for Birds Eye cannery.

I noticed that some stubs documented payment of Mom’s union dues. I recall that she had friends who worked in that cannery, which was across town in the Seabright area. One of Mom’s friends, Mrs. Silva, was mentioned in Margaret Koch’s August 1958 article, “Working in Cannery is Better But No Cinch” (Santa Cruz Sentinel).

Koch began by stating the obvious: “Working in a cannery is no bed of roses,” but, she added, “for the 5oo women who trim pears and shove hot string beans into canning machines at Stokely-Van Camp, it's a lot better today than it used to be.” When the article was published, the cannery had a $700,000 annual payroll. It employed “500 women and 250 men during the three summer months and 40 to 50 full-time year 'round employees.”

Two of the women interviewed—Mrs. Josephine Silva and Mrs. Minnie Pollastrini—had worked there for many years, and had been there even before laws were instituted to prevent youth from working at the plant. They spoke with amused irony about the first conveyor belt:

"Remember the first conveyor belt?" one said, and from the way they both laughed you could tell it had been a long-standing joke between them. It was a blessing for making the work easier and quicker, but it made them all sea-sick until they got used to working on it, they explained.

The cannery’s nurse, Genevieve Hamilton (called Kelly, for some reason) was treating a worker’s arms. She explained that “some of the women are allergic to the fruits and vegetables, and their arms may break out with rashes.” I suspect that the problem was more likely with the pesticides used on the produce in the agricultural fields.

The cannery provided a very noisy environment in which to work:

The whole place clatters and bangs. And here at the door of the canning building, a solid sheet of sound came rolling out like a physical blow. There was the hiss of steam, the clanking of hundreds of empty, moving tin cans, and underneath all the thrum of powerful machinery. Unending, stretching, reaching out to every corner, the sound was a smothering thing. And because of it, the huge open building seemed airless.

I was really happy to come across Koch’s article, because it’s well-written, and fills in a number of details, sensory and otherwise, about my mom’s cannery job. I knew that Mom’s first days of working at the Birds Eye cannery conveyor belt made her nauseous, and that she had to see the nurse. Based on the written notes on two of her pay stubs, I was sorry to see that she had to see a nurse at the Stokely cannery, too!

I only knew about how noisy cannery work was because we lived across the street from the Birds Eye cannery, and I could hear the clatter from my bedroom.

ART

Urban Sketching, or . . . ?

The ink drawing above, of some businesses in San Francisco’s Chinatown, was drawn from life. I was sitting in a car near Jackson Square, waiting for someone. This is what I, and many others, would call “urban sketching,” which means that you “draw on location.”

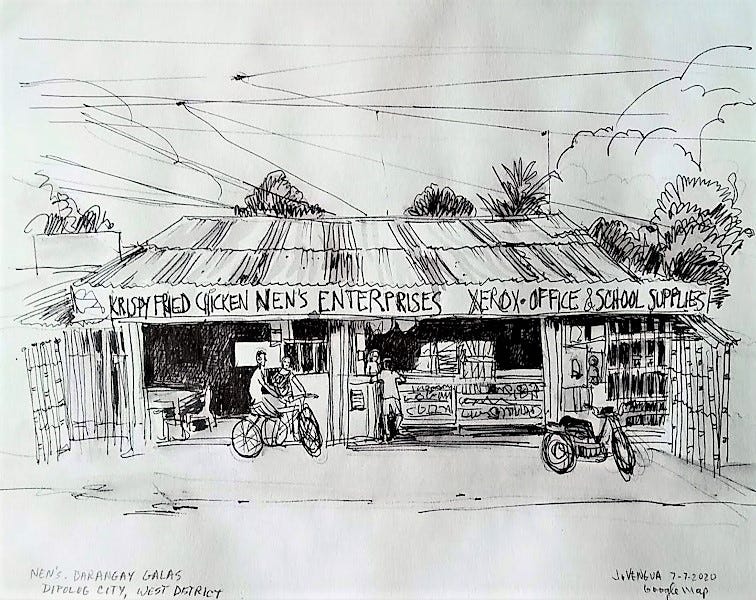

But most of the sketching I’ve done for my letter project has used images from old photographs, as in the completely digital drawing below, from the Japantown section of Lake St. in Salinas Chinatown, or analog drawing taken from Google Maps, as in the photo below that.

So, what do I call the last two drawings? Historical sketching? Memory sketching? Narrative sketching? But it doesn’t depend so much on memory or narrative as on archival research. So maybe it’s archival sketching from various sources including old photos and online sources. I’m not trying to create an exact copy of a photographic image; I’m translating a photographic image to the hand-drawn, analog medium of sketching. I like “archival sketching.”

RABBIT HOLE

As in the previous issue, I think I’ll continue to post grant, mutual aid, and residency resources, just to see what’s still available for artists and writers—despite all the bad news about grant and aid monies drying up.

Mutual Aid Resources

Why mutual aid matters now more than ever, from Real Change.

As fire season begins in California, Western Arts Alliance offers mutual aid for Southern California fire victims.

Mutual Aid for Artists and Musicians: Rebuilding Creativity After Disaster— from Safety Compliance Services. They offer a list of mutual aid and emergency grants.

Stimpunks: Mutual Aid and Human-Centered Learning for Neurodivergent and Disabled People

Grants & Residencies

The Arts Council for Monterey County wants to support YOU! Their current grant cycle just ended, but that gives you time to put together a proposal for next year’s cycle.

Art at Work Program (Blueline Arts) opportunities for artists to exhibit in the Sacramento/larger Placer County area (California); ongoing - no deadline.

UCSF Artist Residency. The 2024 artist was Filipino American Ruth Tabancay:

Yaddo Artists Residency (current deadline in August), Saratoga Springs, New York. Congrats to my friend Marianne Villanueva for receiving a residency at Yaddo!

Artists & Writers

Composer/Percussionist Susie Ibarra wins the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for Music for her work “Sky Islands.” Here are excerpts from her interview with Asia Society, where she speaks about the magic of the “sonic ecosystem of the rainforest” and culture in the Philippines. (See also highlights from her performance in Soundings, below):

Five on the Western Edge, a poetry reading at Bird & Beckett Books, featuring San Francisco Bay Area pioneering poets Beau Beausoleil, Steve Brooks, Larry Felson, Hilton Obenzinger, and Stephen Vincent. Thanks to author Joselyn Ignacio for sending the video. And do check out Ignacio’s new book, River Waves Back, available at Barnes & Noble. “The monsoon-flooded fields and dirt lanes of a province in Luzon and the literary side streets of San Francisco are the settings of River Waves Back, the story of a girl traversing time and space.”

Gaza Poets Society: “My Death is Not a Song for You to Sing” (on Substack).

Lisa Angulo Reid reports on Ruby Ibarra’s wonderful win for NPR’s Tiny Desk Concert competition; be sure to check out the video!

Congrats to Aileen Cassinetto for receiving the Foley Prize for poetry from America: the Jesuit Review! Aileen’s Paloma Press published my chapbook Marcelina: A Meditation on the Murder of Cecilia “Celing” Navarro in 2020.

SOUNDINGS

Highlights from Susie Ibarra’s “Sky Islands” features the Extended Filipino Talking Gong Ensemble with Claire Chase on flute, Alex Peh on piano, and Levy Lorenzo and Ibarra on percussion, joined by the four-member Bergamot Quartet comprising violinists Ledah Finck and Sarah Thomas, violist Amy Huimei Tan and cellist Irène Han.

Bosco Session - featuring Marcus Grimm:

My gratitude goes to everyone who reads Eulipion Outpost regularly, and especially to those who have subscribed or donated on my Ko-fi page to support my efforts.

My ongoing appreciation goes to the Mysterious M. for his excellent editing skills.

Website and blog: Jeanvengua.com

A Crooked Mile (a blog)

CommonwealthCafe (Filipino American & AAPI history and print archives)

Eulipion Outpost is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

WWII historian Salvatore Mercogliano reports that Japan sent out three squadrons of I-boats in 1941 to “wreak havoc” on US Merchant Marine ships before their attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1942.