The Art of Migration

#171: Mom's Migration; More Mail Art, Walead Beshty, Howardena Pindell, Lindsey Levendall & Talula, Maryrose Cobarrubias Mendoza, Gana, and Hoh Rainforest.

THEN & NOW

While reading letters from the period when my mom finally migrated to San Francisco, I think of my relationship to travel and mobility: how colonial trade’s utilization of Philippine seafaring skills shaped the future of work for Filipinos, especially those who migrated to other lands; how American citizenship changed everything for my parents, and not necessarily for the better; how U.S. historical narratives have emphasized “exploration” and “pioneering” as uniquely American; and how these stories shape our goals and perceptions of mobility—from running and hiking (while tracking our miles) and van life, to our fixation with cars and trucks, and the privileges of global travel and tourism.

Recently, I started a blog that focuses on mobility and living without a car in A Crooked Mile. I did this as a separate “newsletter,” although each post would be brief (blog format), as compared to Eulipion Outpost. But now I’m wondering if it would be better to put it in a “sub-section” within this newsletter. It would initially go out to everyone on my mailing list, including subscribers, but—according to Substack—you would be able to opt out. Should I keep it separate, or put it in a sub-section in Eulipion Outpost? I would love to hear from you in comments, and appreciate your feedback.

Mom’s Migration

On April 10, 1950, Mom mailed a letter to my dad, letting him know that this was her last day in the Philippines; at midnight she would be boarding the SS President Cleveland, bound for San Francisco. She expected to arrive on May 3rd. Dad would be at sea, but his trusted friends, Paul and Pilar Laput would be there to greet her. Nevertheless, she hoped that he would be able to arrive in San Francisco soon. On April 11, 1950, she sent him another letter and a Radiogram to confirm the details.

I know from conversations with my Mom that the entire voyage had been miserable; she suffered seasickness during much of the journey. To make matters worse, she was still recovering from her hospitalization for influenza and an infection.

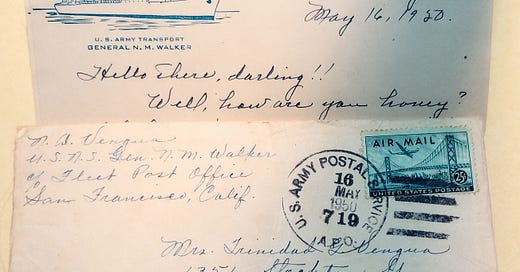

On May 16, Dad sent a cheery letter from the U.S. Army Transport General N.M. Walker to his San Francisco address, asking how my mother was, explaining his lateness, but assuring her that he would be arriving on May 29th or 30th:

You see, we’re behind . . . schedule now on account of an unexpected breakdown at sea. One of the boiler got busted. And there was a storm in Okinawa. To avoid it, we have to slow down until the next day.

He then explained that he had a month’s leave coming up, but warned that they wouldn’t have much money to spend, because he would have to use much of his paycheck to pay off debts incurred aboard the ship.1 He ended the letter on a positive note: “Signing off now darling. Please take care of yourself well. Remember honey, we got a date ! ! !”

Mom and her family had been relieved that the war in the Philippines was finally over, allowing them to work and plan for the future, so I think it would’ve been hard for them to take seriously the news that yet another war was brewing in Korea. But the United States would soon become embroiled in that conflict, in which over 2 million persons would perish. During the late 1940s, Dad worked on ships transporting troops out of Korea. He would soon be on ships carrying troops back to the region as the Cold War era began its grim journey into the future.

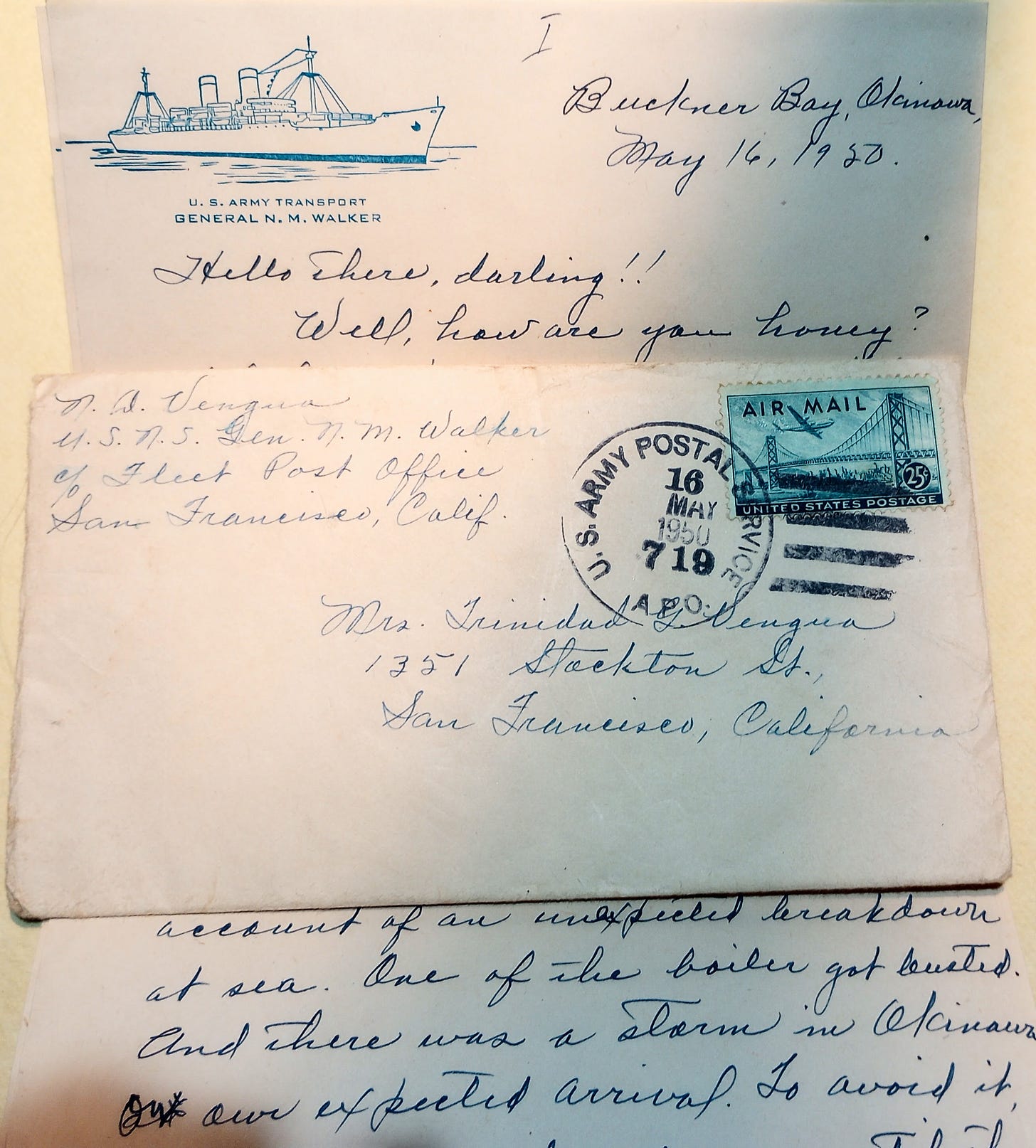

By autumn, 1950, Mom was still hatching plans to bring her sister to San Francisco, where she could hopefully be accepted at a college and finish her degree in education. Knowing how tiny the Stockton St. apartment was, it’s hard for me to understand how Mom could conceive of living there with her sister, especially when Dad came home on leave. However, as she noted several times in her letter to Dad of October 15, she was “lonesome,” and her sister would help to mitigate that. And why wouldn’t she be lonesome? Dad was gone for months at a time.

The two sisters were still fresh from the liberation of Manila, when crowds of Filipinos had cheered and embraced the American soldiers and Philippine guerillas who had risked their lives to save them. Like many Philippine families, the Groyons had opened their home and hospitality to the soldiers. Their expectation was that the U.S. would also welcome them with open arms.

But the history of Filipinos in America provides a counter-narrative that began much earlier when Filipino men were contracted to work in the agricultural fields of Hawai’i and in California and the Pacific Northwest during the 1920s-30s. My father was among them. As the lowest-paid workers among Chinese, Japanese, and Sikh migrants, Filipinos formed unions and protested much more vigorously for higher wages than their employers had expected. They responded to the strikers with racism and violence.

That feeling of being allies certainly helped when Filipinos began migrating to the U.S. and sought the citizenship that had been denied to them until the end of WWII. But white soldiers and military staff returning to civilian life would receive priority when it came to jobs. As a foreigner, it would also have been much harder for my aunt to enter a university in the U.S. than in the Philippines. I think neither sister was prepared for the hardships that living in the U.S. would bring.

In the end, my grandmother’s wishes prevailed. It had been hard for her to lose her eldest daughter when she migrated to the U.S. She did not want to lose another daughter to that continent across the sea—so my aunt stayed in Manila, and finished her degree there.

On December 20, 1950, Mom sent a Christmas card to Dad. He would not be home for her first Christmas in the U.S. He was sailing on the USNS Aiken Victory—one of the ships that would take him to the Marshall Islands when the U.S. conducted nuclear testing.

She included a brief, typewritten letter, noting that my paternal uncle Mike had arrived in San Francisco with his daughter Barbara in tow, and that they would all journey 80 miles south to the beach town of Santa Cruz to spend Christmas with my uncle’s family. Mom would learn that a post-war housing development was under construction in that area, and that knowledge would initiate some exciting plans for the near future.

Darling, I wish you’re coming back soon & spend our Christmas with me. I’m signing off now and goodnite & sweet dreams dear —Love always, Trining

ART

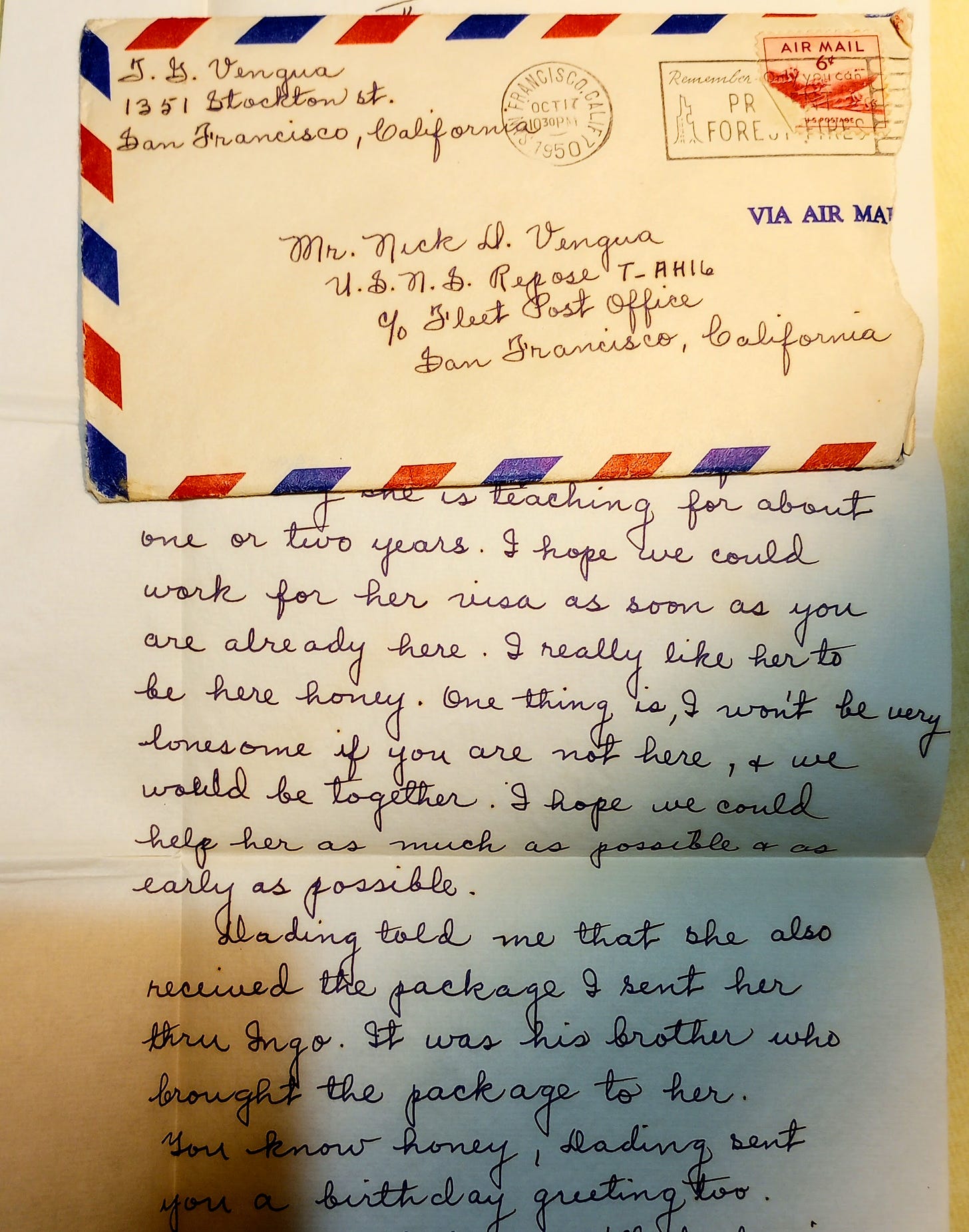

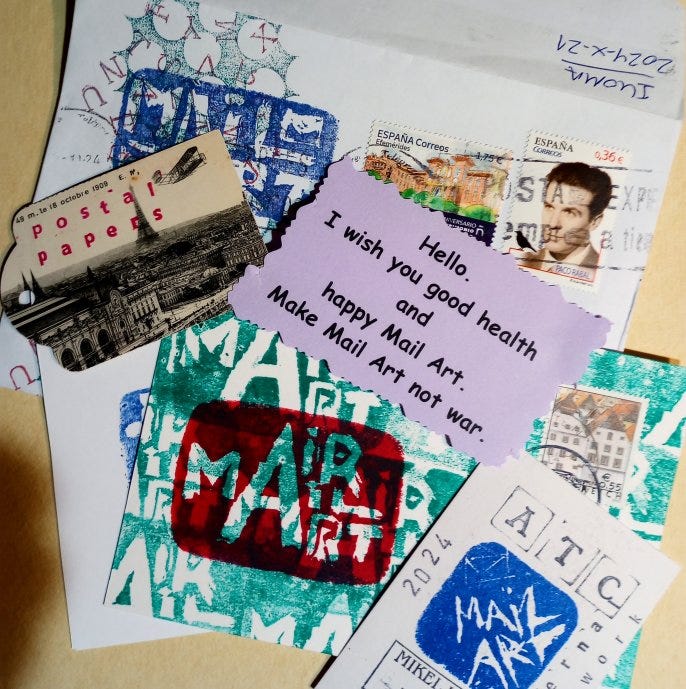

Mail Art is a kind of migratory art—because it reaches out, beyond a computer or mobile phone. Venturing beyond national or state boundaries, it touches you with evidence of material life far away. It can be subversive, poetic, beautiful, playful, and silly. To date, I have received mail art from the American Midwest and Pacific Northwest; from the Netherlands, Brazil, and Spain. Here are two works of mail art I have received, and two that I’ve sent out:

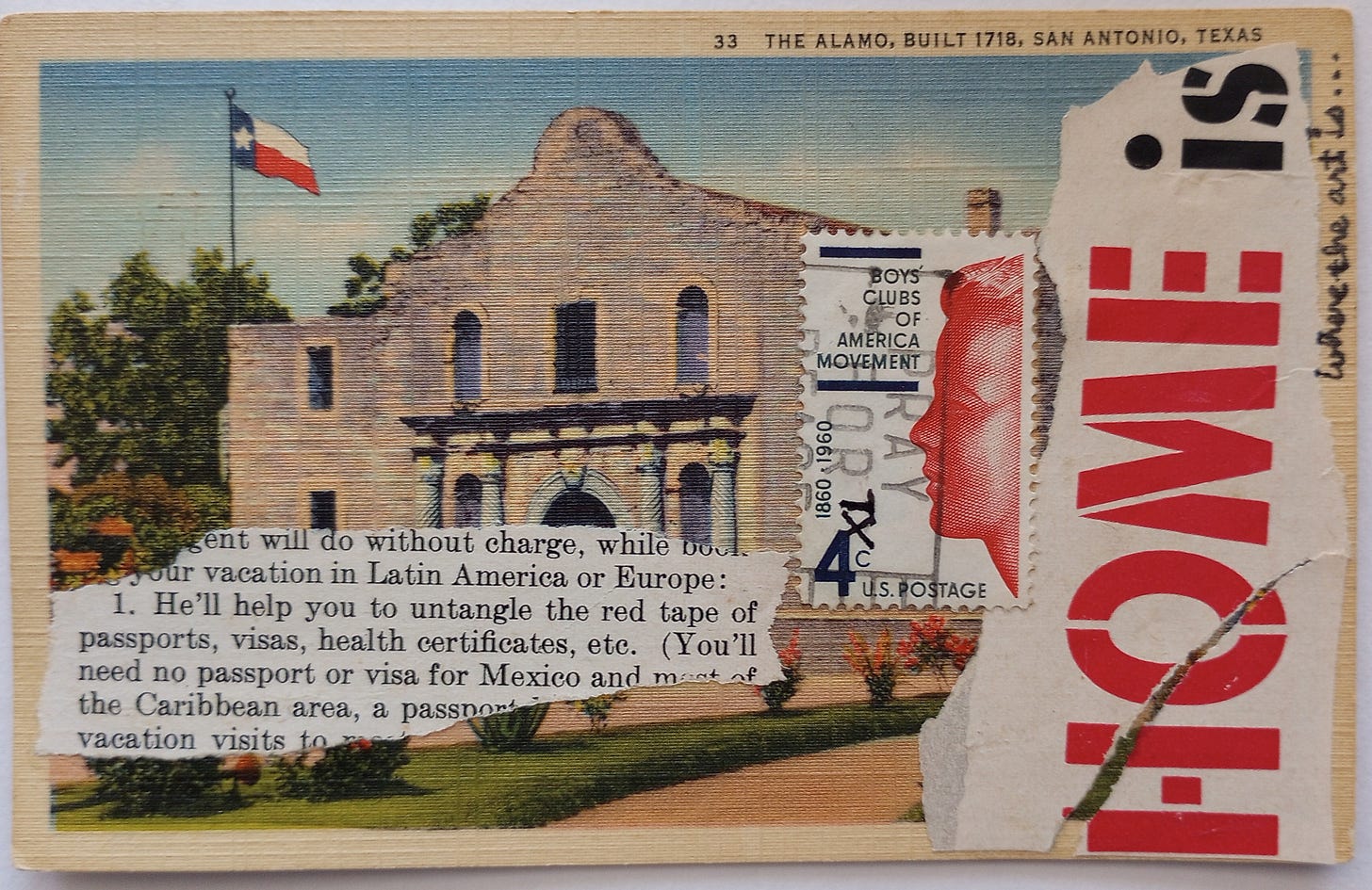

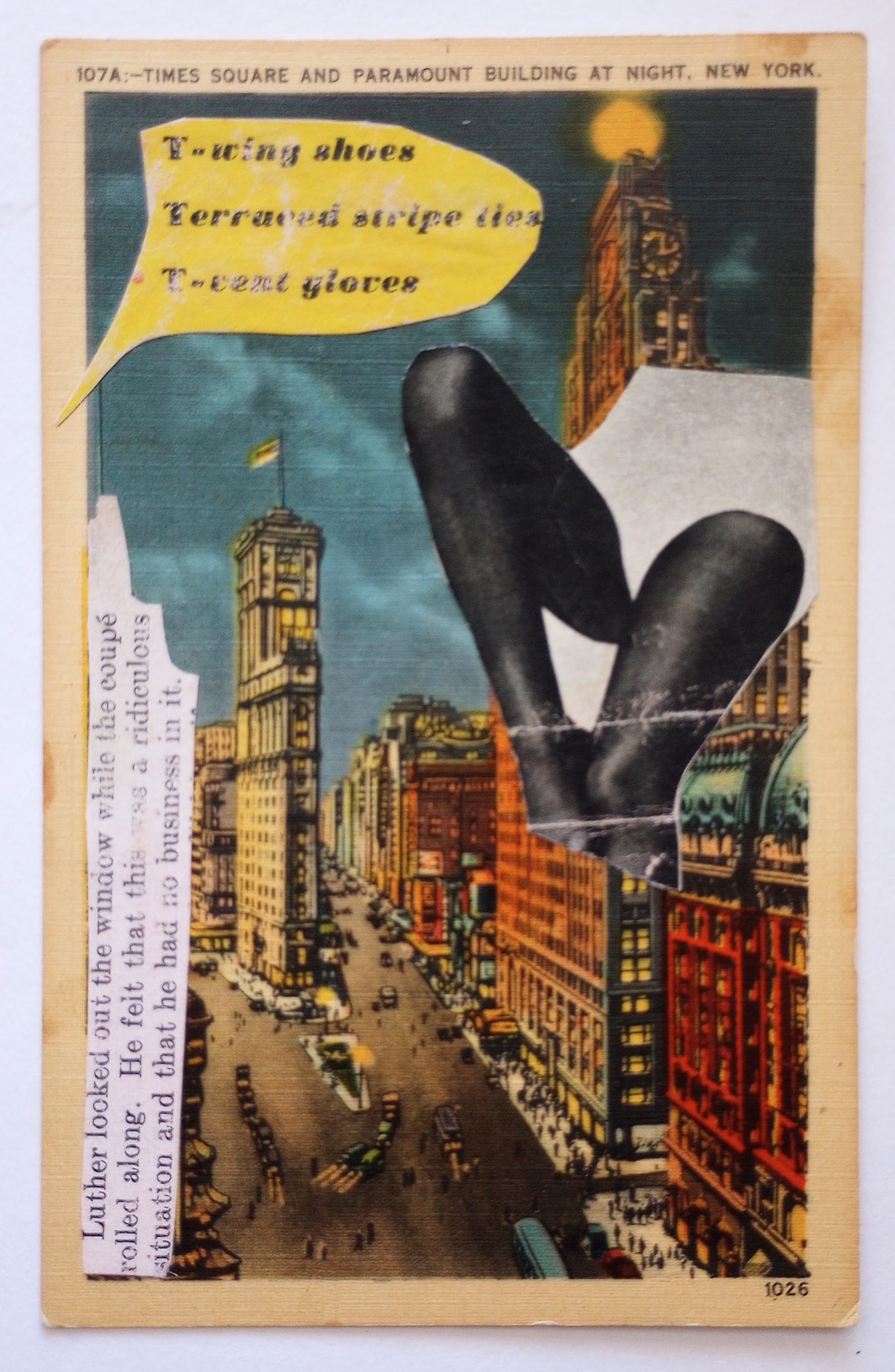

Two collage postcards that I made and mailed out:

RABBIT HOLE

Aside from its migratory nature, I like the transparency and materiality of mail art (as opposed to digital and AI art). Also, many of my works are small because my mobility and finances are limited.

Artist Walead Beshty notes, “I tend to think of my work in terms of constraints, whether that be context, convention or material, and use their logics to generate the work. I guess that’s because I see life as an improvisation within constraints, and affirmative notions of selfhood, autonomy, freedom, etc., arise through the active negotiation with restriction.”2 His work often exposes the systems and infrastructures that go into the aesthetic presentation of art.

"I don't want to teach a lesson or provide a recipe, but I actively try not to conceal. Power works by concealing how it functions, by enforcing a ritual, naturalizing it. This makes the means through which power functions camouflaged, and power itself sublime. [My italics]. I try to avoid this as much as possible, and part of this is to situate the production of the work in a public or common structure, one that is accessible, ubiquitous, instead of tacitly claiming artistic inspiration or selfhood as a justification for a work."3 —Walead Beshty

Howardena Pindell describes her circular format as “a kind of internal gravity”

Father and Daughter artist duo (Lindsey Levendall and Talulah ) :

Multi-disciplinary artist Maryrose Cobarrubias Mendoza4 works with “ideas of loss, memory, and play toward reimagination and transformation.” Here she discusses her process:

SOUNDINGS

The following two videos are from Listening to Earth, LLC:

Gana sings a song from his native Mongolia. The unnamed videographer notes that Gana was “one of our in-country partners during my study abroad in Mongolia 2015. He, my other Mongolian instructors, and the nomadic families we encountered on the steppe were always sharing songs.”

Sound of the Hoh Rainforest on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington State:

Thanks for reading Eulipion Outpost! Special thanks to readers who have donated here on Substack or in my Ko-fi page to support my efforts!

I have a website and blog. And check out A Crooked Mile.

Eulipion Outpost is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

He had also helped to pay for Mom’s passage to the U.S. on the President Cleveland.

Walead Beshty: Pulleys, Cogwheels, Mirrors, and Windows, ex. cat. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Museum of Art), p. 25.

Thanks to Eileen Tabios for pointing out the work of Cobarrubias Mendoza on Facebook.

I'd include your mobility thread in Eupilion.

I follow both separately, but it may be convenient to read in one sitting. It could follow the main post before the Rabbit Hole.

Love the exchange of letters!